Download documents and transcripts

Teachers' notes

This collection of documents introduces students and teachers to the English Reformation through the original State Papers held at The National Archives. They have been selected and introduced by historian of the period, Dr Natalie Mears of Durham University. Students and teachers can use the documents to develop their own questions and explore their own lines of historical enquiry on different aspects of the Reformation in England across the whole Tudor period, from Henry VIII to Elizabeth I.

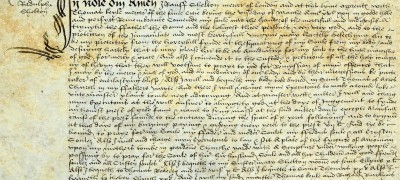

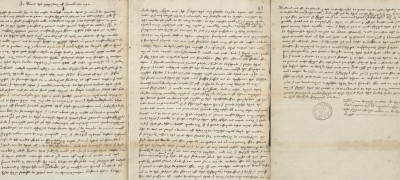

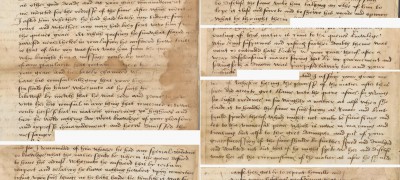

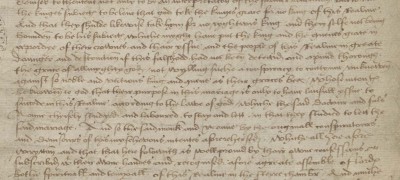

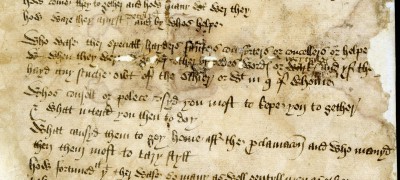

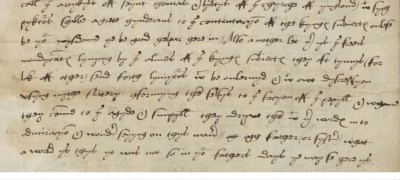

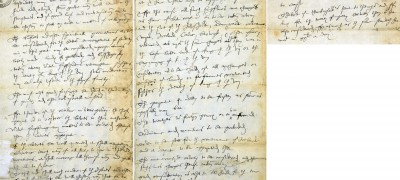

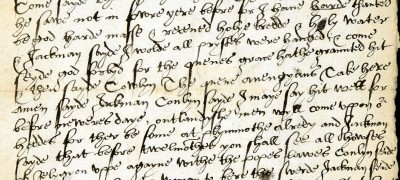

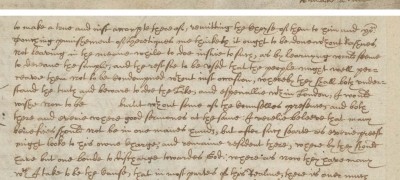

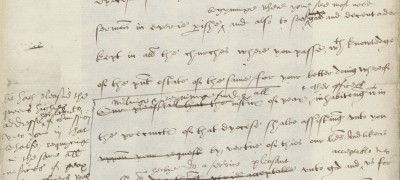

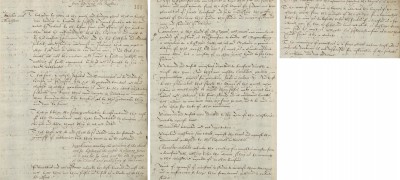

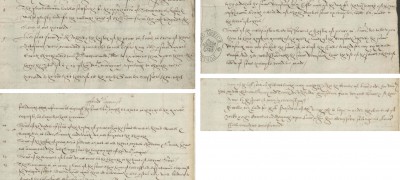

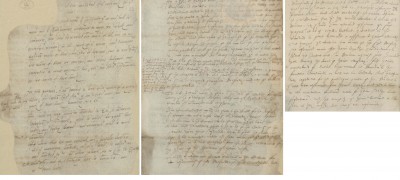

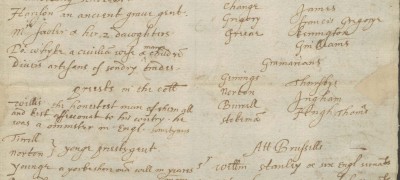

The documents included here reflect some of the ways in which men and women, young and old, royal (SP10/13/35) and poor (SP1/82, fs. 69r-72v), experienced these transformative changes. How they sought more (SP12/86/47) or less (SP1/94, f.1& 2) change; how they responded to religious texts (SP1/74, f.96v-97v) and rumours (SP10/9/57); how they worshipped (SP1/203 f.85r-90r), and what practical problems some faced as a result of religious change (SP1/144 f. 85r). They emphasise how change was contingent (SP1/142, f.73r-73v) and contested both between the state and its subjects (SP12/199/1) and within the state (SP10/15/15). Moreover, they show how such contention could arise as much for political reasons as for ideological ones (SP63/154/37). Most importantly, perhaps, they show how the state and its subjects perceived change, and defined themselves and their opponents. We can see, for instance, not only the priorities of Mary’s government in the restoration of Catholicism (SP11/1/5), but also how the state responded to, and characterised, its opponents, whether that was through information-gathering (SP12/269/69) or by criticising and satirising opponents’ concerns (SP10/8/6). And we can see how some willingly ‘bought into’ reform and offered, or were happily employed by the state to offer, advice (SP12/240/138) – some of which could be critical (SP12/240/138).

We hope that these records offer students the opportunity to develop their powers of evaluation and analysis and can be used in creating course work. The collection is broad enough to develop a series of different lines of enquiry and will support a range of ability. Alternatively, teachers may wish to use the collection to develop their own resources or even encourage students to ‘curate’ their own ‘exhibition’ of the most significant sources on particular aspects of the Reformation. All documents are captioned and provided with transcripts. We have only modernised the spelling and also added punctuation where appropriate to make them more accessible, as Tudor writers wrote very long sentences. However, we have strictly retained the original form of words. Difficult vocabulary is explained in square brackets. Thumbnail text is provided to give a sense of the document content and themes at a glance as displayed on the web page. Finally, a bibliography is provided for teachers of the topic.

Connections to curriculum

These documents can be used to support any of the exam board specifications for GCSE and A level covering the political, social and cultural aspects of the English Reformation in the 16th century.

AQA: GCSE History

Unit 2C –Enquiry in depth: Elizabethan England, 1558–1603, part 3: religious matters: question of religion, English Catholicism and Protestantism

Edexcel: GCSE History

Option B4: Early Elizabethan England 1556-88, key topic 2: The ‘settlement of religion’

OCR: GCSE History A (Explaining the Modern World)

British Depth Study: The English Reformation c1520-c1550

OCR: GCSE History B Schools History Project

British Depth Study: The Elizabethans 1580-1603

AQA: GCE A level

Triumph of Elizabeth, 1563–1603

Edexcel GCE A level

Breadth Study: Option B1: England 1509-1603: authority, nation and religion: Religious changes 1509-88

OCR GCE A level

Enquiry Topic: Mid Tudor Crises 1547-1558: Key topic: Religious changes

British Period Study: Elizabethan England: Elizabeth and Religion

Introduction

by Dr Natalie Mears, University of Durham

The Reformation was one of the most transformative events in the history of the British Isles. Not only did it profoundly (although ultimately slowly and haphazardly) change people’s religious beliefs, but it also ushered in important political, constitutional, social and cultural change. Moreover, it played a fundamental role in the establishment of national identity. It defined England (Wales and Ireland were ignored; Scotland was a separate power) as a new Israel. That is to say, an island bastion of the true (i.e. protestant) faith, especially favoured by God and physically separated from largely Roman Catholic (and hence corrupt and tyrannical) continental Europe. Indeed, our understanding of the Reformation – and, therefore, the histories written of it – has been shaped precisely by these factors ever since John Foxe’s ‘Actes and monumentes’ (commonly known as the ‘Book of Martyrs’).

Was this all because Henry VIII fell in love with Anne Boleyn? Certainly, the combination of Henry’s need for a male heir to rule over a patriarchal society, his infatuation for Anne, and her determination not to be just the king’s mistress were all significant triggers. But it seems likely that home-grown evangelicalism (in England’s case, left over from the Lollard movement) and the dissemination of reforming ideas from abroad would, sooner or later, have effected some sort of ‘Reformation’, as it did in other continental countries.

It would be a mistake, however, to think that the Reformation in England, Wales and Ireland was a forgone conclusion. The Henrician Reformation was notoriously haphazard, not least because Henry himself – despite pushing from Anne, Thomas Cranmer and Thomas Cromwell – was never really convinced by evangelicalism. His realms could have remained jurisdictionally ‘semi-detached’ from the Papacy (he was too fond of the supremacy to give it up) while remaining religiously close to Rome. Similarly, had Edward VI not died unexpectedly in 1553 – he was not the sickly boy of legend, but relatively robust one with a liking (if not the skill) for jousting as well as an impressive hat collection – the Tudor Reformation may have been distinctly less idiosyncratic and more in line with continental beliefs and practice, than it ultimately was. And, as Christopher Haigh and Eamon Duffy have shown that the Tudors’ dominions remained largely Catholic until at least 1580, if Mary had lived or produced an heir then the Reformation could have fizzled out altogether.

Ultimately, what these documents show is that we need to pay as much, if not more, attention to how people articulated their ideas and beliefs, as to what they articulated: the language they used, the ritual actions they employed, the way they defined themselves and others, and how their perceptions shaped the way they acted. The Reformation may have ‘begun’ with Henry VIII’s beliefs about his marriage and the succession and his emotions regarding Anne Boleyn, but its real story lies in the beliefs, actions, perceptions, and prejudices of his subjects.

Reading list

This is a full, but by no mean comprehensive, reading list for the Reformation, covering England, Wales and Ireland. The material is mixed: some of the items are books, but many are journal articles which you will primarily find in, or via, a university library.

Reading list on the English Reformation c1527-1590, (PDF, 0.07MB)

External links

Stories from the Collection: Thomas Cromwell

Records at The National Archives about Thomas Cromwell.

Back to top