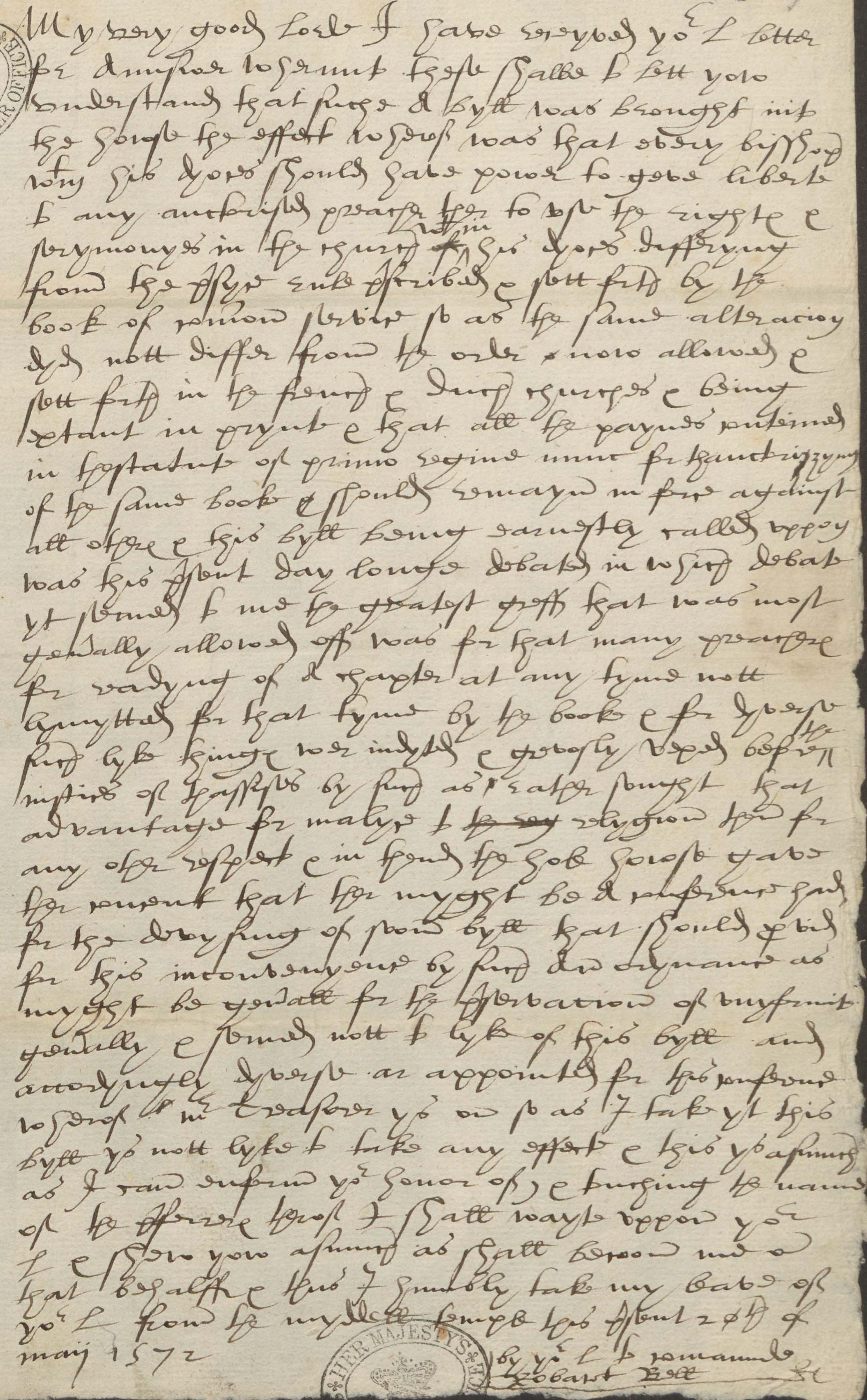

Robert Bell, Speaker of the House of Commons, to Lord Burghley, 20th May 1572, TNA catalogue ref: SP12/86/47, f.204r

The Book of Common Prayer was not popular with the puritans partly because it was based on the Catholic Sarum Rite. The Sarum Rite was the liturgical form used in most of the English Church prior to the introduction of the first Book of Common Prayer in 1549. Puritans also felt that ‘set prayer’ (established formats that were repeated) lulled congregations into boredom and were meaningless. The parliament of 1572 saw one of a number of attempts to revise, abolish or supplement the BCP.

Transcript

My very good Lord, I have received your Lord’s letter for answer whereunto these shall be to let you understand that such a bill was brought into the house [House of Commons] the effect where of was that every bishop within his diocese should have power to give liberty to any authorised preacher there to use the rites & ceremonies in the church within his diocese differing from the precise rule prescribed & set forth by the book of common service so as the same alteration did not differ from the order now allowed & set forth in the French & Dutch[1] churches & being extant in print & that all the pains contained in the statute of primo regine unuc [Act of Uniformity] for the authorising of the same book & should remain in force against all others & this bill being earnestly called upon was this present day long debated in which debate it seemed to me the greatest grief that was most generally allowed of was for that many preachers for reading of a chapter at any time not limited for that time by the book & for divers such like things were indicted [criticized or complained of] & grievously vexed before the justices of the assizes [justices of the peace] by such as rather sought that advantage for malice to the religion then for any other respect & in the end the whole house gave their consent that there might be a conference had for the devising of some bill that should provide for this inconvenience by such an ordinance as might be general for the preservation of uniformity generally & seemed not to like of this bill and accordingly diverse are appointed for this conference where of Mr Treasurer[2] is on so as I take it this bill is not like to take any effect & this is as much as I can inform your honour of, & touching the names of the preferrers [those who had introduced and supported the bill] thereof & shall wait upon your Lord & show you as much as shall become me on that behalf & thus I humbly take my leave of your Lord from the Middle Temple [one of the Inns of Court where lawyers studied and practiced. It still exists in London].

This present 20th of May 1572 by your lord to command

Robert Bell

[1] This specifically refers to the ‘stranger churches’ – i.e. churches attended by, and run by, exiles communities from France and the Netherlands – in London and elsewhere. The specific liturgies referred to here are those of Valerand Poullian (Liturgia Sacra, 1551), Marten Micron and Petrus Datheen.

[2] Sir Francis Knollys, Treasurer of the Chamber, and the regime’s main ‘manager’ of the House of Commons at this time. Knollys approved of the bill, arguing ‘‘that diverse mischiefs grew by the straitness of the statute for uniformity of common prayer’. He knew that the bill was likely to annoy Elizabeth and had the criticisms of the BCP deleted from the bill’s preamble, and got some of the more radical proposals omitted, but when Elizabeth requested to see the bill and, as Knollys predicted, disliked it. He defended it and though it was passed, Elizabeth refused to give it the royal assent so it never became law.