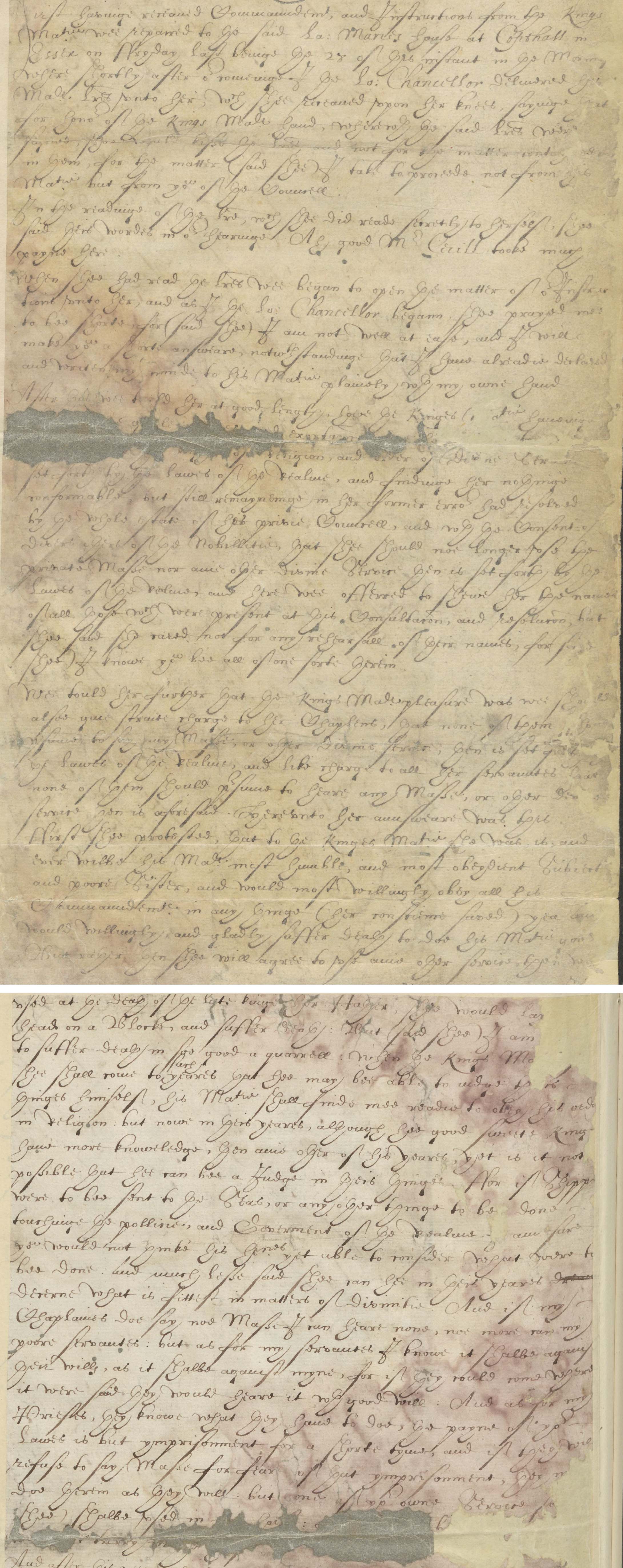

Report to the Privy Council of the delivery of their message to Princess Mary by [Lord Rich], Lord Chancellor, [Sir Anthony Wingfield], comptroller of the household and Sir William Petre, Secretary, 29 August 1551 (SP10/13/35, f.71r-71v)

In August 1549, Edward had written to Mary requesting that she used the new Book of Common Prayer in her household, though had licensed her to hear mass alone in her own chambers. By 1551, Edward wanted Mary to conform fully. We tend to associate resistance, and the using of illness to evade questioning and conformity, to Elizabeth (under Mary); however, in this letter, Mary adopts similar actions and provides a very feisty response to the councillors. Note also that she argues that Edward should not be instituting religious reform before he has reached his majority, an argument that had also been put forward by Stephen Gardiner at the beginning of the reign.

Transcript

First having received Commandment, and Instructions from the King’s Majesty, we repaired to the said Lady Mary’s house at Copthall in Essex on Friday last, being the 28th of this instant in the morning, where shortly after our coming, I the Lord Chancellor delivered his Majesty’s letter unto her, which she received upon her knees, saying that for honour of the King’s Majesty’s hand, where which the said letters were signed, she would kiss the letters, and not for their matter contained in them, for the matter (said she) I take to proceed not from his Majesty but from you of the Council.

In the reading of the letter, which she did read secretly to herself,[1] she said these words in our hearing: Ah good Mr Cecil [William Cecil, later Lord Burghley and principal secretary and Lord Treasurer to Elizabeth I] took much pain here.

When she had read the letters we began to open the matter of our Instructions unto her, and as I the Lord Chancellor began she prayed me to be short for (said she) I am not well at ease, and I will make you a short answer, notwithstanding that I have already declared and written my mind to his Majesty plainly with my own hand.

After that, we told her at good length how the King’s Majesty having used all the gentle means and exhortations that he might to have reduced her to the rights of the religion and order of divine service set forth by the laws of the realm, and finding her nothing conformable but still remaining in her former error, had resolved by the whole estate of his privy council, and with the consent of divers others of the nobility, that she should no longer use the private Mass nor any other divine service then is set for the by the laws of the Realm, and here we offered to shew her the names of all those which were present at this consultation, and resolution, but she said she cared not for any rehearsal of their names, for (said she) I know you be all of one sort therein.

We told her further that the King’s Majesty’s pleasure was we should also give straight charge to her chaplains, that none of them [should be] present to say any Mass, or other divine service then as set forth by the laws of the Realm, and like charge to all her servants that none of them should presence [be present] to hear any Mass, or other divine service as aforesaid. Here unto her answer was that first she protested that to the King’s Majesty she was, is, and ever will be his Majesty’s most humble, and most obedient Subject and poor Sister, and would most willingly obey all his commandments in anything (her conscience saved) yes and would willingly and gladly suffer death to do his Majesty’s good, But rather then she well agree to use any other service then which

[f.71v]

used at the death of the late king her father she would lay her head on a block and suffer death. But (said she) I am unworthy to suffer death in so good a quarrel: when the king’s Majesty said she shall come to such years that he may be able to judge things himself, his Majesty shall find me ready to obey his orders in religion: but now in these years, although the good sweet king have more knowledge than any other of his years, yet is it not possible that he can be a judge in these things. For if ships were to be sent to the seas, or any other thing to be done touching the policy and government of the realm I am sure you would not think his years yet able to consider what were to be done: and much less said she can he in these years discern what is fittest in matters of divinity. And if my chaplains do say no Mass I can hear none, now more can my poor servants but as for my servants I know it shall be against their wills, as it shall be against mine, for if they could come when it were said they would hear it with good will. And as for my priests, they know what they have to do, the pain of your laws is but imprisonment for a short time,[2] and If they will refuse to say Mass for fear of that imprisonment, they may do herein as they will: but none of your own Service (said she) shall be used in my house and if any be said in it I will not tarry in the house

…

[1] She read the letter herself (rather than have it read to her) and read it silently. In the 16th century it was common, even when reading to oneself, to read aloud.

[2] The Edwardian regime prided itself that it did not burn anyone for heresy.