’20 People of the 20s’ is part of 20sPeople – our season to mark the release of the 1921 Census, connecting the 1920s and the 2020s.

’20 People of the 20s’ is part of 20sPeople – our season to mark the release of the 1921 Census, connecting the 1920s and the 2020s.

This story was researched by Iqbal, Regional Community Partnerships Manager. Iqbal is currently enrolled on the History PhD programme at King’s College London, researching racism and empire in the interwar years. He first came across the story of Claudius Smart while working on a project about the 1919 Race Riots.

The merchant seaman from Liverpool

An illustration of Claudius Smart, from the photograph on his merchant seaman identity card. By Sophie Glover.

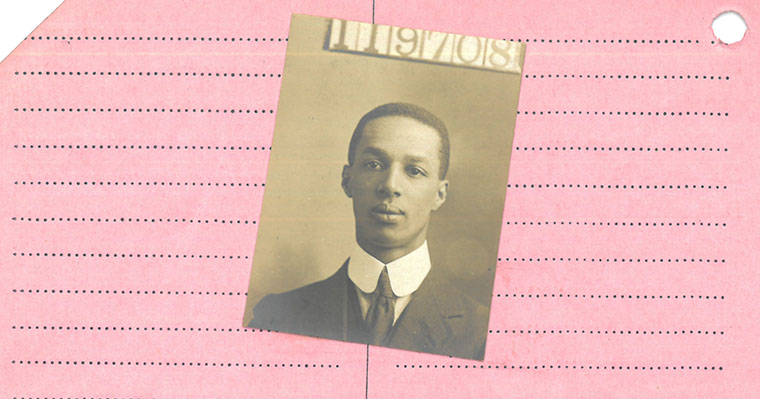

Claudius Alexander Smart was born in 1894 in Kingston, Jamaica. In his merchant navy card, which would have been issued between 1918-1921, his nationality is given as British, like his father. He’s listed as an engineer, a well-paid job requiring a good education and technical skills. His photo shows a young, smartly dressed man. However, his story is far from straightforward.

Writing to the Colonial Office in January 1921, Claudius states that he feels ‘a stranger among strange people’. This is a poignant hand-written letter from a man who served on British merchant ships, settled, married and started a family in Liverpool, yet was forced to return to Jamaica in the wake of the 1919 race riots.

He expresses the personal cost of this on him and his family: his desperation is evident as he highlights that, despite trying very hard, he cannot find any employment at a time when thousands are unemployed, while also being doubly disadvantaged due to the colour of his skin. Claudius’ original letter can be found in our upcoming exhibition, ‘The 1920s: Beyond the Roar’.

‘I am a stranger among strange people, I haven’t a friend to give, or do anything for me. I have no hope of finding employment here, as there are thousands native of the country unable to find employment, and again I have been seeking work for the last month, every day, and I can see no sign of my efforts being likely to be rewarded.’

Married to a white woman and with a young child, he is unable to find work and requests passage back to Jamaica in the hope he can earn enough money to send for his family. Indeed, Claudius is yet to be found in the 1921 Census, suggesting he returned to Jamaica prior to June 1921. There were obstacles to his departure, however: he states pressure is being placed on him by his father-in-law – Edward Sears, local businessman – with the help of the police, to ensure he leaves a financial guarantee for his family’s care. Claudius and his wife, May, struggled financially after getting married on 26 March 1920 in Liverpool. May bore a child shortly after marriage. Edward Sears refused to assist them. The story of their interracial marriage is described as a ‘sordid history’.

Correspondence from the Colonial Office during this period repeatedly states that assistance will only be given if May grants her consent for Claudius to leave. According to further correspondence, the couple are interviewed by police – May refuses to give her consent as she will be left with no means of support; Claudius disputes this in his letter, explicitly stating that she has given him permission to leave. Correspondence days later indicates that the situation is unresolved.

The next mention of the case is not until 1922, when Wirral Poor Law Union write to the Home Office asking for funds to help look after Claudius’ wife and child. They tell how both have been left destitute and are being maintained by local taxes. The Union complains that if his family couldn’t go with him, some means should have been put in place for Claudius to contribute. In the same letter Claudius is mentioned as now living with his mother, who is described as an English woman. He has been earning 12 pounds and 15 shillings per month, so potentially is able to send for them.

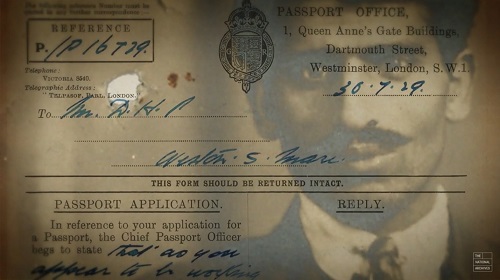

Claudius Smart’s merchant seaman identity card, found in Glamorgan Archives

The opportunities for employment across the world and in many parts of Britain’s empire led men from Africa, Asia, the Caribbean and the Middle East to seek work in wealthier parts of the world. People who came to Britain were not simply aliens or foreigners, but also British; in fact, those from the Caribbean knew Britain as their mother country and English as their mother tongue. They had grown up considering themselves British, as demonstrated in a letter in our collection from Jamaican seafarer James Gillespie, who refers to himself as one of ‘Briton’s sons’. The war and its fall-out ultimately changed everything.

The rioting in 1919 was a marker for this change: the black presence in Britain first came to notice nationally, and there was much commotion about the right of black people to reside in Britain. This fuelled a political backlash, leading to actions to repatriate men to the colonies. Across correspondence held at The National Archives, it’s possible to read about numerous tussles around the issue of repatriation in this period.

This post war period drew out what has been referred to as the betrayal of the idea of imperial citizenship¹. For people like Claudius Smart, being made to feel an alien was even more of an affront than being subjected to racial slurs. Put simply: he felt like a stranger.

1 – (Drawing the Global Colour Line, Lake and Reynolds, p5)

A Stranger in a Strange Place

Claudius’ story has been made into an audio play, ‘A Stranger in a Strange Place’, as part of a partnership with Tamasha Theatre Company and as part of The National Archives’ ‘Once British Always British’ project. The project is a collaboration with playwrights to reimagine the stories of colonial seafarers, drawing on historic Home Office files.

In this short film The Tamasha Theatre Company takes us behind the scenes of the making of ‘Once British Always British’.

At the height of the First World War between 40,000 and 60,000 colonial seafarers served Britain. Many of these men were affected by the 1920 Aliens order and Special Restriction (Coloured Alien Seaman) Order 1925 as ‘Arab’, ‘Asian’, ‘Caribbean’ and ‘African’ men overnight found themselves having to prove they had a right to be in Britain. Find out more about the project here.

20 People of the 20s

’20 People of the 20s’ is a project where staff members at The National Archives have researched a story of someone from the 1920s. From family members and First World War service personnel, to famous performers and politicians, we hope these stories will encourage you to explore the breadth of experience in 1920s Britain.

’20 People of the 20s’ is part of 20sPeople. Find out more here.