Teachers' notes

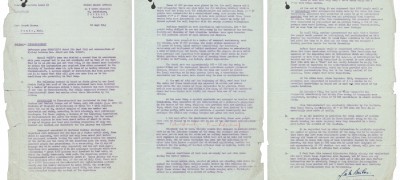

These key documents from The National Archives lend themselves most readily to an analysis of the Allied response to the question of saving the Jews. The documents in the collection are labelled and arranged together according to theme.

Please note some of these documents, particularly towards the end of the collection, are distressing to read. Please be aware of this when presenting to students.

Here are some questions to consider when using these sources but students and teachers may wish to develop their own questions or lines of historical enquiry.

- Is antisemitism an adequate explanation for the Holocaust?

- When did the Nazis embark on the ‘Final Solution’?

- What role was played by collaborators in the Holocaust?

- Why were survival rates of Jews so different across Europe?

- What accounts for the Allies’ (in)actions with respect to saving the Jews?

- How did the victims of the Holocaust understand what was happening to them and what did they do to try and alert the ‘free world’?

- How has the Holocaust been represented in art?

Students could work with a group of sources on a certain question or linked theme. We hope that the documents will offer students a chance to develop their powers of evaluation and analysis and support their course work. Teachers can also use the collection to develop their own resources or encourage students to ‘curate’ their own ‘exhibition’ of the most significant sources on the topic. Finally, there is an opportunity to consider film sources as interpretations of these events in relation to the documents by following the link to Pathé.

Further extension work on the topic of the Holocaust requiring more document research could involve the following topics:

- post-war occupation of Germany

- the creation of displaced persons camps

- ‘illegal’ emigration for Palestine, refugee policies.

Connections to the Curriculum

These documents can be used to support any of the exam board specifications covering Germany and the Second World War:

AQA GCSE History 1B Period study Germany 1890-1945: Germany under the Nazis: Social policy & practice.

AQA GCE History ‘A’ level

The Nazi experiment 1929-49: Social developments including the racial state

Edexcel: GCE History ‘A’ level

Aspects of life in Germany & West Germany 1918-89: Nazi racial policies

OCR GCE History ‘A’ Level Unit Y221 Democracy and Dictatorships in Germany 1919-1963: Impact of war and defeat on Germany 1939-49

OCR AS Level

Unit Y251 Interpretation topic: Impact of war and defeat on Germany 1939-49

OCR GCSE

Living under Nazi Rule: Occupation: The Holocaust, ghettos and the death camps

National Curriculum Key stage 3

Study of the Holocaust

Introduction

In unleashing the Second World War, the Nazi regime was responsible for the deaths of around 50 million people, including civilians and soldiers. The Nazis and their allies committed genocide against Europe’s Roma, murdered millions of Catholic Poles and Soviet Prisoners of War, and caused death and destruction throughout occupied Europe. The genocide of the Jews that has come to be known as the Holocaust was both intertwined with and separate from these other killings.

For the Nazis, murdering the Jews was part of a vast scheme for the racial reorganisation of Europe, which would create a pan-European Germanic empire with ‘Nordics’ at the top of the hierarchy, Slavs at the bottom, and Jews eliminated. At the same time, the Nazi obsession with the Jews was different from the way it regarded other ‘races’: Jews were both hated and feared and – at least at the level of the Nazi leadership – were regarded as the masterminds behind a vast world conspiracy that aimed to destroy the ‘Aryan race’.

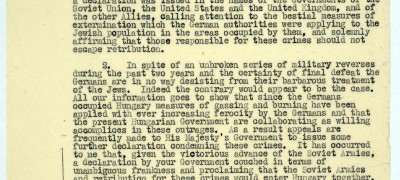

Many of the regimes that allied themselves with Nazi Germany – especially Croatia, Romania, Slovakia, Vichy France and Hungary – found that the Nazis’ anti-Jewish obsession chimed with their own aspirations for creating ethnically homogeneous nation states. Even if they were not as driven by antisemitism as the Nazis, such regimes made use of the atmosphere created and licence granted by the Nazis to fulfill their own ambitions. As a result, as it played out across Europe, the Holocaust was so far-reaching because of the role played by collaborators, from states to institutions such as auxiliary police battalions, to individuals.

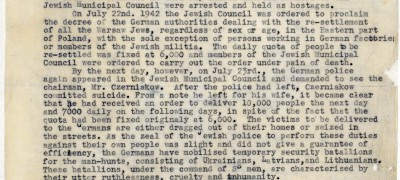

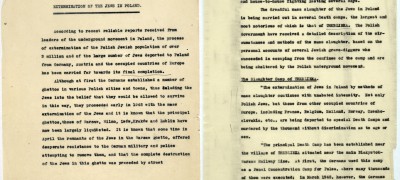

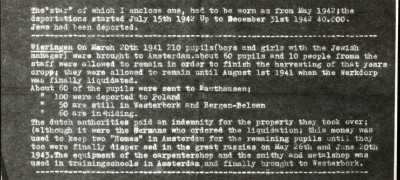

As the documents in this important collection show, the murder of the Jews was a complex series of interrelated events. There was not one single, unidirectional policy that saw Jews everywhere in Nazi-occupied Europe ghettoised and then deported to death camps. Rather, the experiences of different Jewish communities were very different, depending on what sort of occupation regime they lived under, the attitude of local administrations, the extent of SS penetration in the area, military circumstances, the Germans’ need for labour – especially towards the end of the war – and other factors such as possibilities for escape, hiding or resistance. What we call ‘the Holocaust’ was a continent-wide crime: a series of vastly different experiences for all involved, united by the fact that everywhere the Nazis aimed to kill Jews as and when they could.

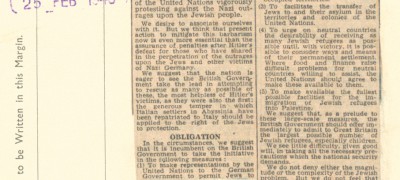

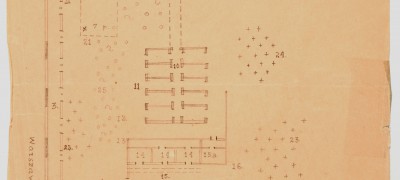

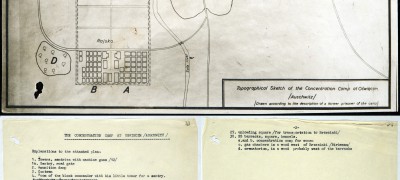

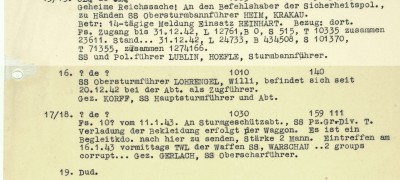

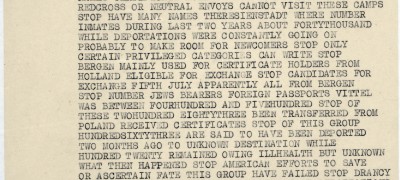

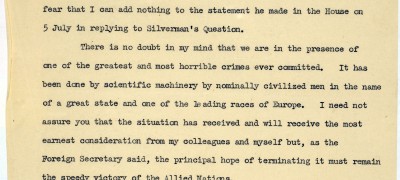

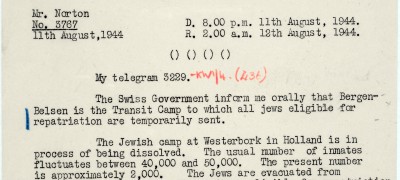

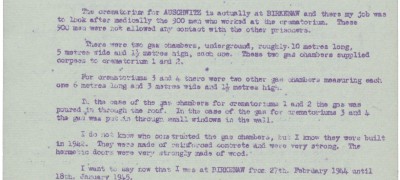

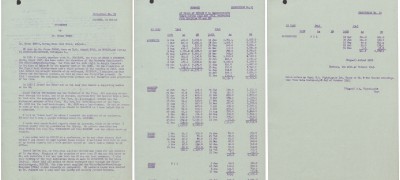

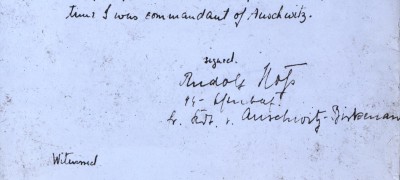

The complexity of the Holocaust means that documents such as the Riegner telegram or the Lichtheim telegram are all the more remarkable, since they show that some concerned contemporaries were trying to make sense of what the Nazis were doing to Europe’s Jews. Plans of the Auschwitz and Treblinka camps, reports from the Warsaw ghetto and from Polish representatives in London, all show that knowledge of the murders was circulating. Nevertheless, it was only in July 1944, when most of the Jews of Hungary (the last remaining large Jewish population group in Europe outside of Russia) had already been murdered, that Churchill could write that ‘we are in the presence of one of the greatest and most horrible crimes ever committed.’ In other words, how to interpret the documents remains a matter of historical debate: do they show that the Allies understood that the Nazis intended to wipe out the Jews and that therefore they should have done more to save them? Or should they not be read in isolation but placed in the broader context of wartime issues, which might reveal that they were received and understood piecemeal, so that no real comprehension of the extent of Nazi plans prevailed? In the presence of images such as Violette Le Coq’s drawings of Ravensbrück (in The National Archives because they were used as evidence at the 1946 Ravensbrück trial), such questions might seem irrelevant. But beyond the fact that the Nazis killed six million Jews, more or less destroying an ancient civilisation, only questions such as these, which rely on documents such as those held at The National Archives to establish interpretations and meanings, can help us in some measure to grapple with the enormity of the Nazis’ crimes.

Dan Stone

Professor of Modern History

Royal Holloway, University of London

External links

The Collection at the National Holocaust Centre and Museum

The National Holocaust Centre and Museum.

The Holocaust Educational Trust

Quiz yourself on Adolf Hitler

How much do you know about Adolf Hitler and the rise of Nazism in Germany?

Adolf Hitler

Was Hitler a 'passionate lunatic'?Belsen concentration camp 1945

What did the British find when they entered Belsen concentration camp?Chamberlain and Hitler 1938

What was Chamberlain trying to do?German occupation of the Rhineland

What should Britain do about it?Hitler assassination plan

How did the British plan to kill Hitler?Kindertransport

Saving refugee children?Quiz yourself on: Adolf Hitler

How much do you know about Adolf Hitler and the rise of Nazism in Germany?