Report on eyewitness accounts of Theresienstadt (catalogue reference WO 309/377)

Transcript

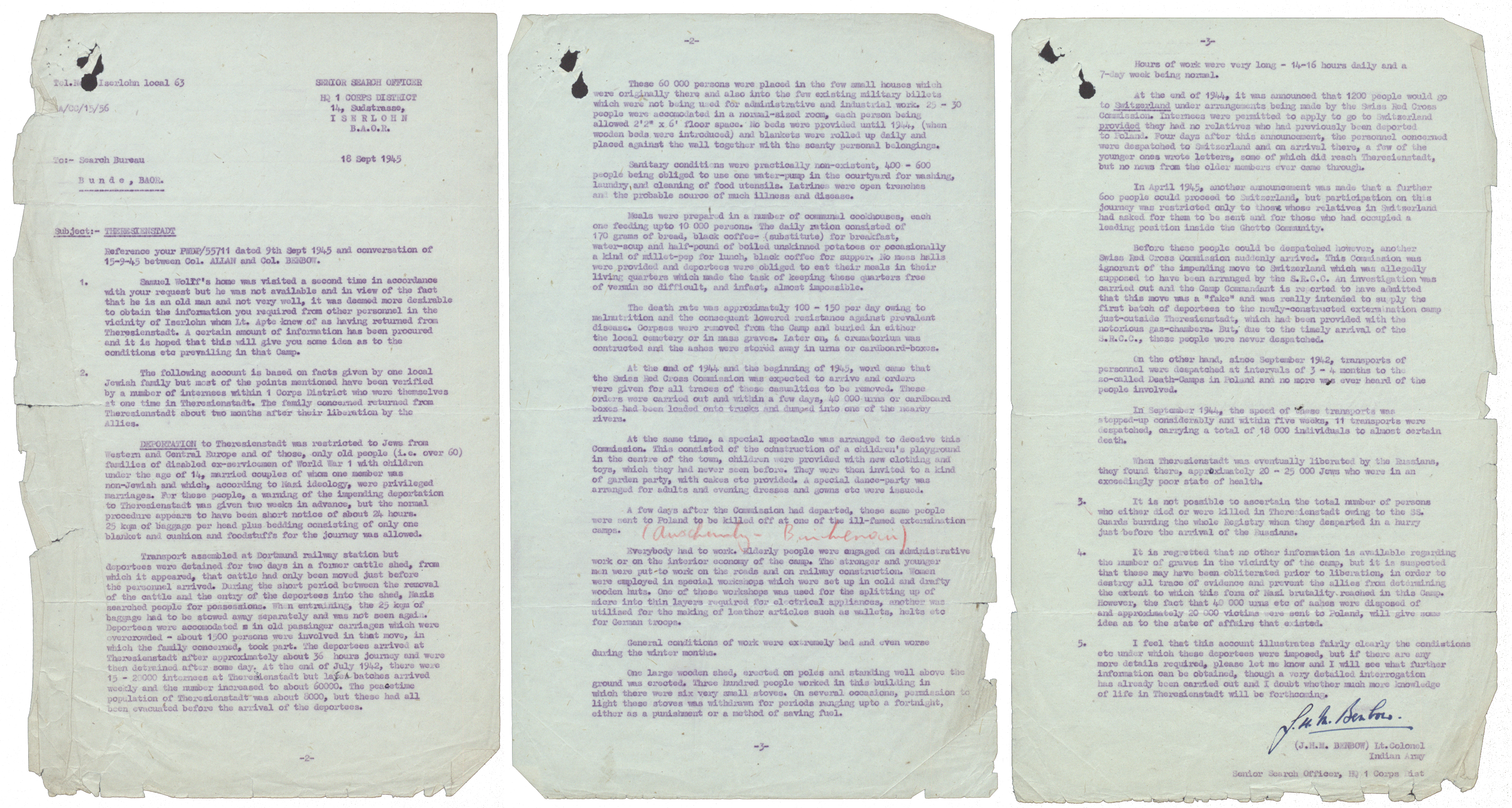

Senior Search Officer

HQ 1 Corps District

14, Sudstrasse,

Iserlohn

B.A.O.R.

To: – Search Bureau

Bunde, BAOR. 18 Sept 1945

——————–

Subject: – Theresienstadt

Reference your PWDP/55711 dated 9th Sept 1945 and conversation of 15-9-45 between Col. ALLAN and Col. BENBOW.

1. Samuel Wolff’s home was visited a second time in accordance with your request but he was not available and in view of the fact that he is an old man and not very well, it was deemed more desirable to obtain the information you required from other personnel in the vicinity of Iserlohn whom Lt. Apte knew of as having returned from Theresienstadt. A certain amount of information has been procured and it is hoped that this will give you some idea as to the conditions etc prevailing in that Camp.

2. The following account is based on facts given by one local Jewish family but most of the points mentioned have been verified by a number of internees within 1 Corps District who were themselves at one time in Theresienstadt. The family concerned returned from Theresienstadt about two months after their liberation by the Allies.

DEPORTATION to Theresienstadt was restricted to Jews from Western and Central Europe and of those, only old people (i.e. over 60) families of disabled ex-serviceman of World War 1 with children under the age of 14, married couples of whom one member was non-Jewish and which, according to Nazi ideology, were privileged marriages. For these people, a warning of the impending deportation to Theresienstadt was given two weeks in advance, but the normal procedure appears to have been short notice of about 24 hours. 25kqm of baggage per head plus bedding consisting of only one blanket and cushion and foodstuffs for the journey was allowed.

Transport assembled at Dortmund railway station but deportees were detained for two days in a former cattle shed, from which it appeared, that cattle had only been moved just before the personnel arrived. During the short period between the removal of the cattle and the entry of the deportees into the shed, Nazis searched people for possessions. When entraining, the 25 kqm of baggage had to be stowed away separately and was not seen again. Deportees were accommodated in old passinger [sic] carriages which were overcrowded – about 1500 persons were involved in that move, in which the family concerned, took part. The deportees arrived at Theresienstadt after approximately about 36 hours journey and were then detrained after some day. At the end of July 1942, there were 15-20000 internees at Theresienstadt but later batches arrived weekly and the number increased to about 60000. The peacetime population of Theresienstadt was about 8000, but these had all been evacuated before the arrival of the deportees.

2

These 60000 persons were placed in the few small houses which were originally there and also into the five existing military billets which were not being used for administrative and industrial work. 25-30 people were accommodated in a normal-sized room, each person being allowed 2’2” x 6’ floor space. No beds were provided until 1944, (when wooden beds were introduced) and blankets were rolled up daily and placed against the wall together with the scanty personal belongings.

Sanitary conditions were practically non-existent, 400-600 people being obliged to use one water-pump in the courtyard for washing, laundry and cleaning of food utensils. Latrines were open trenches and the probable cause of much illness and disease.

Meals were prepared in a number of communal cookhouses, each one feeding upto 10000 persons. The daily ration consisted of 170 grams of bread, black coffee- (substitute) for breakfast, water-soup and half-pound of boiled unskinned potatoes or occasionally a kind of millet-pep for lunch, black coffee for supper. No mess halls were provided and deportees were obliged to eat their meals in their living quarters which made the task of keeping these quarters free of vermin so difficult, and infact [sic], almost impossible.

The death rate was approximately 100-150 per day owing to malnutrition and the consequent lowered resistance against prevalent disease. Corpses were removed from the Camp and buried in either the local cemetary or in mass graves. Later on, a crematorium was constructed and the ashes were stored away in urns or cardboard-boxes.

At the end of 1944 and the beginning of 1945, word came that the Swiss Red Cross Commission was expected to arrive and orders were given for all traces of these casualties to be removed. These orders were carried out and within a few days, 40000 urns or cardboard boxes had been loaded onto trucks and dumped into one of the nearby rivers.

At the same time, a special spectacle was arranged to deceive this Commission. This consisted of the construction of a children’s playground in the centre of the town, children were provided with new clothing and toys, which they had never seen before. They were then invited to a kind of garden party, with cakes etc provided. A special dance-party was arranged for adults and evening dresses and gowns etc were issued.

A few days after the Commission had departed, these same people were sent to Poland to be killed off at one of the ill-famed extermination camps.

Everybody had to work. Elderly people were engaged on administrative work or on the interior economy of the camp. The stronger and younger men were put-to work on the roads and on railway construction. Women were employed in special workshops which were set up in cold and drafty wooden huts. One of these workshops was used for the splitting up of micre into thin layers required for electrical appliances, another was utilised for the making of leather articles such as wallets, belts etc for German troops.

General conditions of work were extremely bad and even worse during the winter months.

One large wooden shed, erected on poles and standing well above the ground was erected. Three hundred people worked in this building in which there were six very small stoves. On several occasions, permission to light these stoves was withdrawn for periods ranging upto a fortnight, either as a punishment of a method of saving fuel.

3

Hours of work were very long – 14-16 hours daily and a 7-day week being normal.

At the end of 1944, it was announced that 1200 people would go to Switzerland under arrangements being made by the Swiss Red Cross Commission. Internees were permitted to apply to go to Switzerland provided they had no relatives who had previously been deported to Poland. Four days after this announcement, the personnel concerned were despatched to Switzerland and on arrival there, a few of the younger ones wrote letters, some of which did reach Theresienstadt, but no news from the older members ever came through.

In April 1945, another announcement was made that a further 600 people could proceed to Switzerland, but participation on this journey was restricted only to those whose relatives in Switzerland had asked for them to be sent and for those who had occupied a leading position inside the Ghetto Community.

Before these people could be despatched however, another Swiss Red Cross Commission suddenly arrived. This Commission was ignorant of the impending move to Switzerland which was allegedly supposed to have been arranged by the S.R.C.C. An investigation was carried out and the Camp Commandant is reported to have admitted that this move was a ‘fake’ and was really intended to supply the first batch of deportees to the newly-constructed extermination camp just-outside Theresienstadt, which had been provided with the notorious gas-chambers. But, due to the timely arrival of the S.R.C.C., these people were never despatched.

On the other hand, since September 1942, transports of personnel were despatched at intervals of 3-4 months to the so-called Death-Camps in Poland and no more was ever heard of the people involved.

In September 1944, the speed of these transports was stepped-up considerably and within five weeks, 11 transports were despatched, carrying a total of 18000 individuals to almost certain death.

When Theresienstadt was eventually liberated by the Russians, they found there, approximately 20-25000 Jews who were in an exceedingly poor state of health.

3. It is not possible to ascertain the total number of the persons who either died or were killed in Theresienstadt owing to the SS. Guards burning the whole Registry when they desparted [sic] in a hurry just before the arrival of the Russians.

4. It is regretted that no other information is available regarding the number of graves in the vicinity of the camp, but it is suspected that these may have been obliterated prior to liberation, in order to destroy all trace of evidence and prevent the allies from determining the extent to which this form of Nazi brutality reached in this Camp. However, the fact that 40000 urns etc of ashes were disposed of and approximately 20000 victims were sent to Poland, will give some idea as to the state of affairs that existed.

5. I feel that this account illustrates fairly clearly the conditions etc under which these deportees were imposed, but if there are any more details required, please let me know and I will see what further information can be obtained, though a very detailed interrogation has already been carried out and I doubt whether much more knowledge of life in Theresienstadt will be forthcoming.

(J.H.M. Benbow) Lt. Colonel

Indian Army

Senior Search Officer, HQ 1 Corps Dist