Download documents and transcripts

Teachers' notes

The purpose of this document collection is to allow students and teachers to develop their own questions and lines of historical enquiry on Protest and Democracy 1819-1820. The documents included primarily cover events at Peterloo, Manchester and during the Cato Street conspiracy in London. Some of the documents relate to:

- Henry Hunt

- female reformers

- yeomanry at Peterloo

- responses to Peterloo

- reading societies

- Cato Street plotters

- Cato Street preparations

- seditious songs

Students could use the documents to write a critical analysis of events at St Peter’s Field. Alternatively, they could explore the reasons why the Cato Street Conspiracy remains a footnote in history – unlike the gunpowder plot – or compare the differences and similarities between the Peterloo massacre and the Cato Street Conspiracy. The records should offer them a chance to develop their powers of evaluation and analysis and support their studies for this period. Another idea would be to see if students can use the documents to substantiate or dispute points made in this introduction to the collection. However, teachers may wish to use the collection to develop their own resources or encourage students to ‘curate’ their own ‘exhibition’ of the most significant sources on the topic. Finally, there is an opportunity to study other documentary sources within our Georgian Britain themed collection, also available on this website, to provide some social context to the period.

The video that sits alongside this collection, Unboxing St Peter’s Field, can be used in connection with several of the documents presented here and our video teacher’s pack complete with questions and activities.

Connections to the Curriculum

These documents can be used to support any of the exam board specifications covering the political, social and cultural aspects of 20th century British history, for example:

AQA History A level

Breadth study: The impact of Industrialisation: Government and a changing society, 1812-1832

Edexcel History A level

Paper 1: Breadth study with interpretations 1D: Britain c1785-c1870 democracy, protest and reform

Paper 3: Aspects in depth: Protest, agitation and parliamentary reform in Britain, c1780-1928: unit: Radical reformers c1790-1819 Mass protest and Agitation

OCR History A level

Unit Y110: From Pitt to Peel 1783-1853

British Period Study: British Government in the Age of Revolution 1783-1832

Introduction

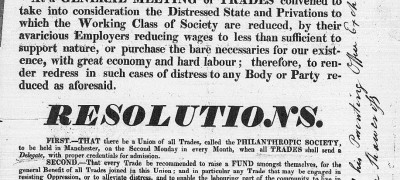

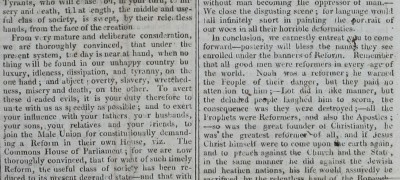

After the failure of rebellion in 1817, economic conditions improved rapidly in 1818. A wave of strikes for higher wages helped to reverse some of the losses of 1816-1817, particularly in the cotton industry. Workers briefly organised a ‘philanthropic union’, an early attempt at a national union of all trades which could support each other in disputes. However, 1819 saw other slumps with widespread wage cuts and unemployment, prompting a second wave of protest for parliamentary reform. This time the radical reformers took care to avoid the failed plots and rebellions of 1817, aiming instead to rally such overwhelming numbers of protestors that the government would be forced to back down.

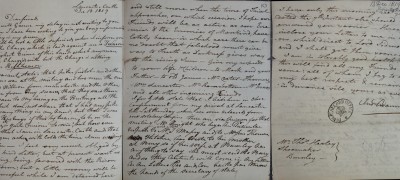

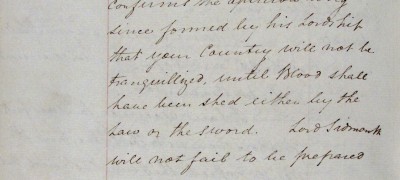

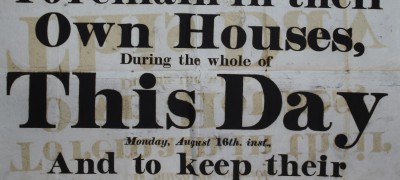

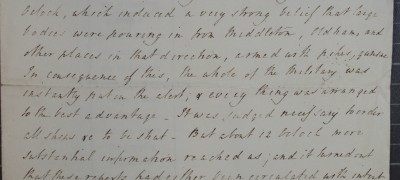

The climax of the national series of mass meetings was a rally of 60,000 people at St Peter’s Fields, Manchester, on 16 August 1819, addressed by the orator Henry Hunt. Hunt called for a peaceful show of strength from across the region: for several weeks beforehand the reformers for miles around practised marching in military formation, drilled by old soldiers, to ensure order on the day. But the local magistrates believed the reformers were preparing for armed rebellion; they declared the meeting illegal and warned people to stay indoors. Several months before, the Home Office had secretly told them: ‘your Country will not be tranquillized, until Blood shall have been shed either by the Law or the sword.’

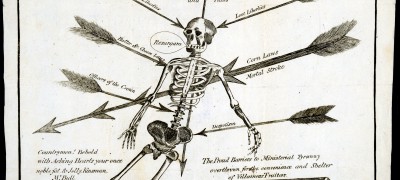

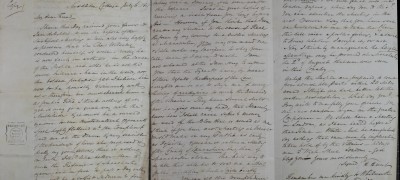

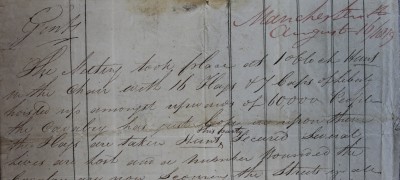

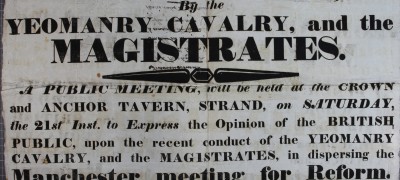

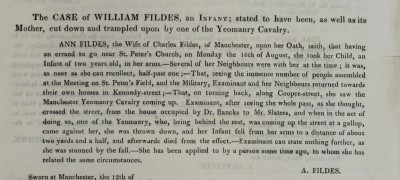

The meeting rallied peacefully with flags, banners, and music, watched by reporters from the national press. As it began the magistrates, fearful of what would happen next, sent in the Manchester Yeomanry (a local volunteer cavalry) to arrest Hunt; they then ordered the regular Hussars to clear the field. The senior magistrate, the Reverend William Hay, fired off a report to London the same evening claiming that rebellion had been averted and injuries had been few; however, cavalrymen such as Major Dyneley wrote enthusiastically of winning ‘the battle of Manchester’ against the ‘enemy’ reformers. Reports in the press, including both the radical ‘Manchester Observer’ and ‘The Times’ of London, told of many deaths and hundreds of casualties, many of them inflicted face-to-face by cavalry sabres, although the authorities tried to discredit individual cases.

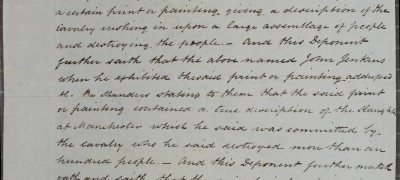

The news of Peterloo spread far and wide, with fairground booths as far away as Devon displaying detailed hand-coloured prints of the scene. There were protest meetings, which led to further arrests, and for a time rebellion appeared to threaten. In the spring of 1820 there was serious unrest in Yorkshire and armed rebellions in Ireland and Scotland; in Glasgow, a provisional government was optimistically proclaimed.

In January 1820, some of the London ultra-radicals plotted to assassinate the Cabinet in the dramatic ‘Cato Street conspiracy’; however, the whole thing was a trap laid by government. The plotters’ every move was watched by informers – yielding some gripping details about London’s tiny but committed revolutionary underground – but they were arrested and executed. 1820 also saw a popular movement which was more difficult to suppress: a campaign in support of Queen Caroline, the estranged wife of the new monarch George IV, who was trying to divorce her. Reformers compared her treatment with that of the female reformers cut down at Peterloo: ‘The same power which scourged us, is oppressing you’ declared radicals from Lancashire. Support for the Queen spread among troops, and there were signs of mutiny among the guards. The radical printer William Benbow excitedly posted bills urging them to imitate the Italian soldiers who had supported a revolution in Naples.

In the end, the forces of the state proved stronger than those of reform. However, at the next crisis in 1832, the government was forced to back down, unwilling to use military force against reformers for a second time.

Dr Robert Poole

University of Central Lancashire [UCLAN], author of ‘Return to Peterloo’

External links

https://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/the-peterloo-massacre

Read more about responses to the Peterloo Massacre

https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/narrative-of-the-cato-street-conspiracy

A contemporary narrative of the Cato Street Conspiracy

https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/documents/education/unboxing-st-peters-field.pdf – Unboxing St Peter’s Field Video Resources

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLSegY__gUYId1qw-5FdOP7yAopQZ1lYvL

A video playlist of Citizens Project’s Archives Alive: Peterloo