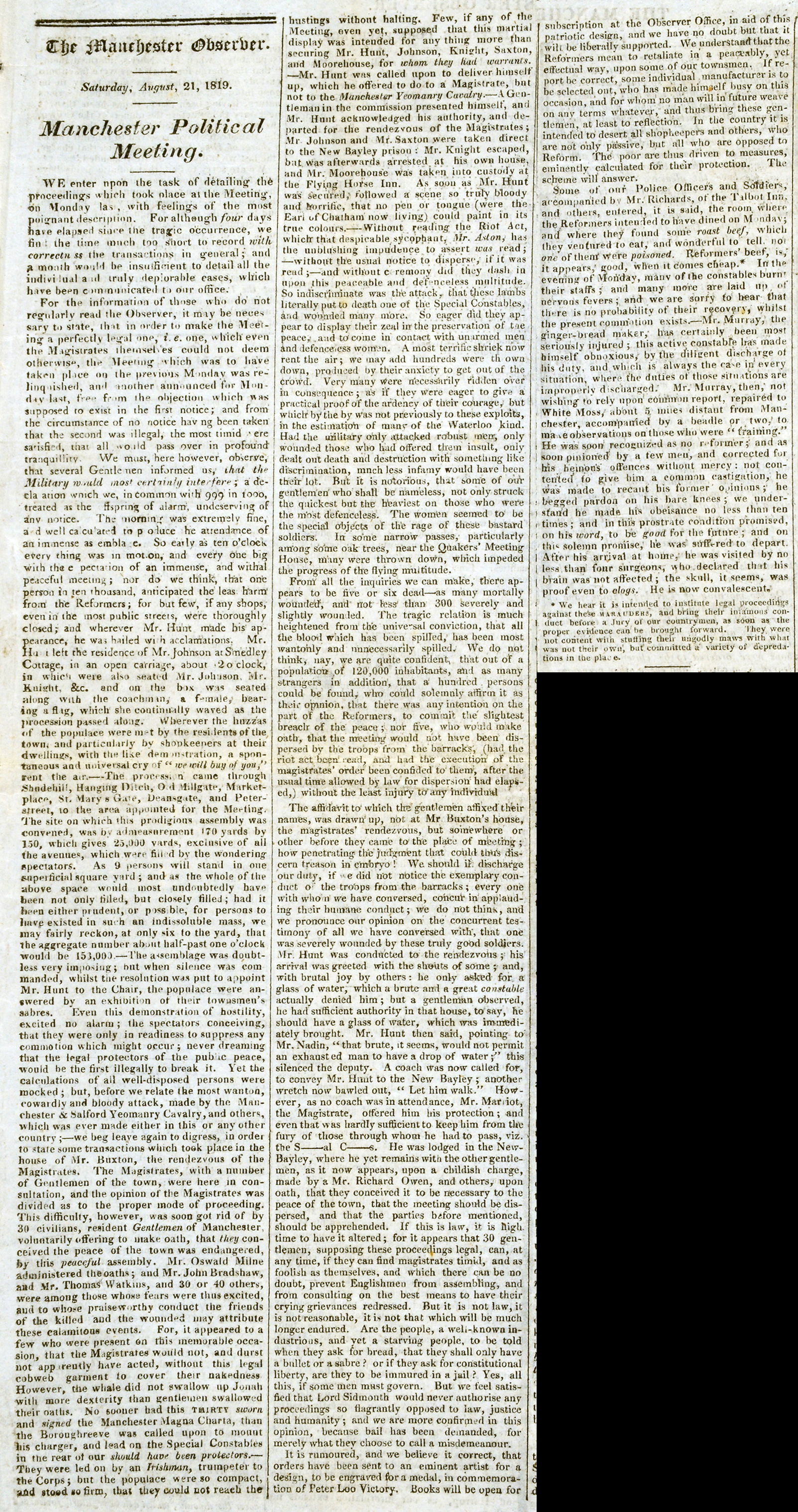

Manchester Observer, 21 August 1819. This was Manchester’s radical newspaper which helped to organise the meeting. (Catalogue reference HO 42/192 f.5)

Transcript

Manchester Political Meeting

We enter upon the task of detailing the proceedings which took place at the Meeting on Monday last, with feelings of the most pregnant description. For although four days have elapsed since the tragic occurrence, we find the time much too short to record with correctness the transactions in general; and a month would be insufficient to detail all the individual and truly deplorable cases, which have been communicated to our office.

For the information of those who do not already read the Observer, it may be necessary to state, that in order to make the Meeting a perfectly legal one, i.e. one, which even Magistrates themselves could not deem otherwise, the Meeting which was to have taken place on the previous Monday was relinquished, and another announced for Monday last, free from the objection which was supposed to exist in the first notice; and from the circumstance of no notice having been taken that the second was illegal, the most timid were satisfied that all would pass over in profound tranquillity. We must, here however, observe, that several Gentlemen informed us, that the military would most certainly interfere; a declaration which we, in common with 999 in 1000, treated as the offspring of alarm, undeserving of notice. The morning was extremely fine, well calculated to produce the attendance of an immense assemblage. So early as ten o’clock everything was in motion, and every one big with the expectation of an immense, and withal peaceful meeting; nor do we think, that one in ten thousand, anticipated the least harm from the Reformers; for but few if any shops, even in the most public streets, were thoroughly closed, and wherever Mr. Hunt made his appearance he was hailed with acclamations. Mr. Hunt left the residence of Mr. Johnson at Smedley Cottage, in an open carriage, about 2 o’clock, in which were also seated Mr. Johnson. Mr Knight &c. and on the box was seated along with the coachman, a female, bearing a flag, which she continually waved as the procession passed along. Wherever the huzzas of the populace were met by the residents of the town and particularly by shopkeepers at their dwellings, with the like demonstration, a spontaneous and universal cry of “we will buy of you”, rent the air. The procession came through Shudehill, Hanging Ditch, Old Millgate, Market-place, St. Mary’s Gate, Deansgate, and Peter-street, to the area appointed for the Meeting. The site on which this prodigious assembly was convened, was by admeasurement 170 yards by 150, which gives 25,000 yards, exclusive of all the avenues, which were filled by the wondering spectators. As 9 persons will stand in one hypothetical square yard; and as the whole of the above space would most undoubtedly have been not only filled, but closely filled; had it been either prudent, or possible, for persons to have existed in such an indissoluble mass, we may fairly reckon, at only six to the yard, that the aggregate number at half-past one o’clock would be 153,000. The assemblage was doubtless very imposing; but when silence was commanded, whilst the resolution was put to appoint Mr Hunt to the Chair, the populace were answered by an exhibition of their townsmen’s sabres. Even this demonstration of hostility, excited no alarm; the spectators conceiving, that they were only in readiness to suppress any commotion which might occur; never dreaming that the legal protectors of the public peace, would be the first illegally to break it. Yet the calculations of all well-disposed persons were checked; but, before we relate the most wanton, cowardly, and bloody attack, made by the Manchester & Salford Yeomanry Cavalry, and others, which was ever made in either this or any other country; we beg leave again to digress, in order to relate some transactions which took place in the house of Mr Buxton, the rendezvous of the magistrates. The Magistrates, with a number of Gentlemen of the town, were here in consultation, and the opinion of the magistrates was divided as to the proper mode of proceeding. This difficulty, however, was soon got rid of by 30 civilians, resident Gentlemen of Manchester, voluntarily offering to make oath, that they conceived the peace of the town was endangered, by this peaceful assembly. Mr Oswald Milne administered the oaths; and Mr John Bradshaw, and Mr. Thomas Watkins, and 30 or 40 others, were among those whose fears were thus excited, and to whose praiseworthy conduct the friends of the killed and the wounded may attribute these calamitous events. For, it appeared to a few who were present on this memorable occasion, that the Magistrates would not, and durst not, apparently have acted without this legal cobweb garment to cover their nakedness. However the whale did not swallow up Jonah with more dexterity than gentlemen swallowed their oaths. No sooner had this thirty sworn and signed the Manchester Magna Charta, than the Boroughreeve was called upon to mount his charger, and lead on the Special Constables in the rear of our should have been protectors. They were led on by an Irishman, trumpeter to the Corps; but the populace were so compact, and stood so firm, that they could not reach the hustings without halting. Few, if any of the Meeting, even yet, supposed that this martial display was intended for any thing more than scaring Mr. Hunt, Johnson, Knight, Saxton, and Moorehouse, for whom they had warrants. Mr. Hunt was called upon to deliver himself up, which he offered to do to a Magistrate, but not to the Manchester Yeomanry Cavalry.—A Gentleman in the commission presented himself, and Mr. Hunt acknowledged his authority, and departed for the rendezvous of the Magistrates; Mr. Johnson and Mr. Saxton were taken direct to the New Bayley prison: Mr. Knight escaped, but was afterwards arrested at his own house, and Mr. Moorehouse was taken into custody as the Flying Horse Inn. As soon as Mr. Hunt was secured, followed a scene so truly bloody and horrific, that no pen or tongue (were the Earl of Chatham now living) could paint in its true colours. Without reading the Riot Act, which that despicable sycophant, Mr. Aston, has the unblushing impudence to assert was read; without the usual notice to disperse, if it was read; and without ceremony did they dash in upon this peaceable and defenceless multitude. So indiscriminate was the attack, that these lambs literally put to death one of the Special Constables, and wounded many more. So eager did they appear to display their zeal in the preservation of the peace, and to come in contact with unarmed men and defenceless women. A most terrific shriek now rent the air; we many add hundreds were thrown down, produced by their anxiety to get out of the crowd. Very many were necessarily ridden over in consequence; as if they were eager to give a practical proof of the ardency of their courage, but which by the by was not previously to these exploits, in the estimation of many of the Waterloo kind. Had the military only attacked robust men, only wounded those who had offered them insult, only dealt out death and destruction with something like discrimination, much less infamy would have been their lot. But it is notorious, that some of our gentlemen who shall be nameless not only struck the quickest but the heaviest on those who were the most defenceless. The women seemed to be the special objects of the rage of these bastard soldiers. In some narrow passes, particularly among some oak trees, near the Quakers’ Meeting House, many were thrown down, which impeded the progress of the flying multitude.

From all the inquiries we can make, there appears to be five or six dead—as many mortally wounded, and not less than 300 severely and slightly wounded. The tragic relation is much heightened from the universal conviction, that all the blood which has been spilled, has been most wantonly and unnecessarily spilled. We do not think, nay, we are quite confident, that out of a population of 120,000 inhabitants, and as many strangers, in addition, that a hundred persons could be found, who could solemnly affirm it as their opinion, that there was any intention on the part of the Reformers, to commit the slightest breach of the peace; nor five, who would make oath, that the meeting would not have been dispersed by the troops from the barracks, (had the riot act been read, and had the execution of the magistrates’ order been confided to them, after the usual time allowed by law for dispersion had elapsed,) without the least injury to any individual.

The affidavit to which the gentlemen affixed their names, was drawn up, not at Mr Buxton’s house, the magistrates’ rendezvous, but somewhere or other before they came to the place of meeting; how penetrating the judgement that could thus discern treason in embryo! We should ill discharge our duty, if we did not notice the exemplary conduct of the troops from the barracks; every one with whom we have conversed, concur in applauding their humane conduct; we do not think, and we pronounce our opinion on the concurrent testimony of all we have conversed with, that one was severely wounded by these truly good soldiers. Mr Hunt was conducted to the rendezvous; his arrival was greeted with the shouts of some, and with brutal joy by others; he only asked for a glass of water, which a brute and a great constable actually denied him; but a gentleman observed, he had sufficient authority in that house, to say, he should have a glass of water; which was immediately brought. Mr Hunt then said, pointing to Mr Nadin, ‘that brute, it seems, would not permit an exhausted man to have a drop of water;’ this silenced the deputy. A coach was now called for, to convey Mr Hunt to the New Bayley; another wretch now bawled out, ‘Let him walk.’ However, as no coach was in attendance, Mr Marriot, the Magistrate, offered him his protection; and even that was hardly sufficient to keep him from the fury of those through whom he passed, viz, the S—l C—s. He was lodged in the New Bayley, where he yet remains with the other gentlemen, as it now appears, upon a childish charge, made by a Mr Richard Owen, and others, upon oath, that they conceived it to be necessary to the peace of the town, that the meeting should be dispersed, and that the parties before mentioned, should be apprehended. If this is law, it is high time to have it altered; for it appears that 30 gentlemen, supposing these proceedings legal, can, at any time, if they find the magistrates timid, and as foolish as themselves, and which there can be no doubt, prevent Englishmen from assembling, and consulting on the best means to have their crying grievances redressed. But it is not law, it is not reasonable, it is not that which will be much longer endured. Are the people, a well-known industrious, and yet a starving people, to be told when they ask for bread, that they shall only have a bullet or a sabre? or if they ask for constitutional liberty, are they to be immured in a gaol? Yes, all this, if some men must govern. But we feel satisfied that Lord Sidmouth would never authorise any proceedings so flagrantly opposed to law, justice, and humanity; and we are more confirmed in this opinion, because bail has been demanded, for merely what they choose to call a misdemeanour.

It is rumoured, and we believe it correct, that orders have been sent to an eminent artist, for a design, to be engraved for a medal, in commemoration of Peter Loo Victory. Books will be opened for subscription at the Observer Office, in aid of this patriotic design, and we have no doubt but that it will be liberally supported. We understand that the Reformers mean to retaliate in a peaceably, yet effectual way, upon some of our townsmen. If reports be correct, some individual manufacturer is to be selected out, who has made himself busy on this occasion, and for whom no man will in future weave on any terms whatever, and thus bring these gentlemen, at least to reflection. In the country it is intended to desert all shopkeepers and others, who are not only passive, but all who are opposed to Reform. The poor are thus driven to measures, eminently calculated for their protection. The scheme will answer.

Some of our Police Officers and Soldiers, accompanied by Mr. Richards, of the Talbot Inn, and others, entered, it is said, the room where the Reformers intended to have dined on Monday; and where they found some roast beef, which they ventured to eat, and wonderful to tell not one of them were poisoned. Reformers’ beef, is, it appears, good, when it comes cheap.* In the evening of Monday, many of the constables burnt their staffs; and many more are laid up of nervous fevers; and we are sorry to hear that there is no probability of their recovery, whilst the present commotion exists.—Mr. Murray, the ginger-bread maker, has certainly been most seriously injured; this active constable has made himself obnoxious, by the diligent discharge of his duty, and which is always the case in every situation, where the duties of those situations are improperly discharged. Mr. Murray, then, not wishing to rely upon common report, repaired to White Moss, about 5 miles distant from Manchester, accompanied by a beadle or two, to make observations on those who were ‘training.’ He was soon recognized as no reformer; and as soon pinioned by a few men and corrected for his heinous offences without mercy; not contented to give him a common castigation, he was made to recant his former opinions; he begged pardon on his bare knees; we understand he made his obeisance no less than ten times; and in this prostrate condition promised, on his word, to be good for the future; and on this solemn promise, he was suffered to depart. After his arrival at home, he was visited by no less than four surgeons, who declared that his brain was not affected; the skull, it seems, was proof even to clogs. He is now convalescent.

* We hear it is intended to institute legal proceedings against these MARAUDERS, and bring their infamous conduct before a jury of our countrymen as soon as the proper evidence can be brought forward. They were not content with stoning their ungodly maws with what was not their own, but committed a variety of depredations in the place.

___________________________________________________