Download documents and transcripts

Teachers' notes

The purpose of this document collection is to allow students and teachers to develop their own questions and lines of historical enquiry on the Georgian period. The documents themselves are titled on the web page so it is possible for teachers and pupils to detect different themes and concentrate on documents on similar topics if they wish. Some of the topics include:

- road transport

- Industrial Revolution

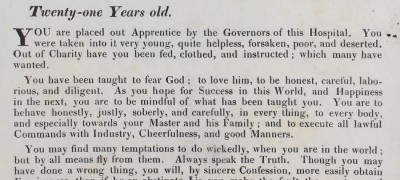

- philanthropy

- design and taste

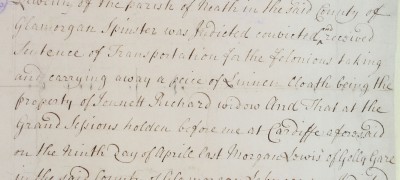

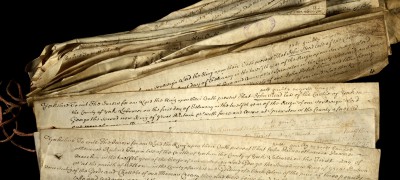

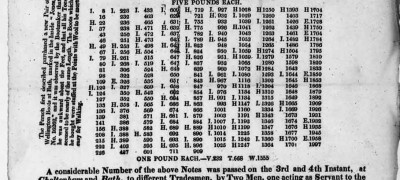

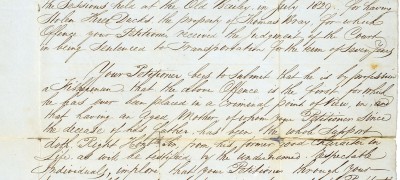

- crime

Students can work with a group of sources on a certain theme or linked themes. We hope that the documents will offer them a chance to develop their powers of evaluation and analysis. Alternatively, teachers may wish to use the collection to develop their own resources or encourage students to ‘curate’ their own ‘exhibition’ of the most significant sources on the topic or they could use the material to provide a sense of period if they are studying the Jacobite Risings of 1715 and 1745.

All of our sources have been provided with a transcript, and more difficult language has been explained in square brackets to support students. Obvious differences in the spelling have not been altered. Each source is captioned and dated to provide a sense of what the document is about. All document images and sound files can be downloaded as a zip file for educational purposes.

The resource includes an introduction by a historian of the period, Amanda Vickery, and there is a link to the family tree of the House of Hanover to help provide further context to the documents.

Finally we have included a Pinterest board on Georgian Britain which offers further focus on the period.

Connections to the curriculum

Key stage 3

National Curriculum in England from September 2014:

The development of Church, state and society in Britain 1509- 1745.

The Restoration, ‘Glorious Revolution’ and power of Parliament.

The Act of Union of 1707, the Hanoverian succession and the Jacobite rebellions of 1715 and 1745.

Key stage 4

AQA

GCSE History (8145) : British thematic studies

This document collection provides documentary content to support these units:

2A Britain: Health and the people: c1000 to the present day

2B Britain: Power and the people: c1170 to the present day

2C Britain: Migration, empires and the people: c790 to the present day

OCR

GCSE, History A, Explaining the Modern World (J410).

This document collection provides documentary content to support unit: War and British Society c.790-2010: The Jacobite Wars 1715 and 1745: Their impact on Scotland and the repression of the Jacobites.

Key stage 5

AQA

A2 History for certification from June 2014.

Unit 3: Stability and War: British Monarchy and State, 1714–1770 (B) HIS3F.

This document collection provides documentary content for section on The Later Years of George II, 1742–1760: The 1745 Jacobite rebellion.

Edexcel

A level History 9H10, Paper 3, Breadth topics:

- Industrialisation and social change in Britain, 1759–1928: forging a new society

- Poverty, public health and the state in Britain, c1780–1939

- Britain: losing and gaining an empire, 1763–1914

- The British experience of warfare, c1790–1918

- Protest, agitation and parliamentary reform in Britain, c1780–1928

This document collection provides documentary content for aspects of life in Georgian Britain.

A level

OCR History H505

British Period study and enquiry (unit group 1): Y109: The Making of Georgian Britain 1678-c1760: Key topic: Aspects of Politics 1714-1780: Jacobitism the ’15 and the ‘45.

Introduction

by Professor Amanda Vickery

No educated continental European would have bothered to read or even speak English in 1700. By 1800 fluent English was a necessity. Why did this happen?

In the 17th century, the British Isles were seen as backward, politically unstable and irrelevant to the rest of Europe. By 1850, Britain was the ‘Workshop of the World’, the centre of the global economy, the richest, most powerful and advanced nation of earth. The 18th century represents one of the most transformative ages in British history.

What caused this transformation? One fundamental factor is immediately clear if we look at British politics and foreign policy. With the Glorious Revolution of 1688, which involved the overthrow of the Catholic king, James II, and the coming to the throne of the Protestant Dutchman, William III, British foreign policy and military potential were driven by a consistent policy hostile to French expansion, both in Europe and beyond. By the time of the victory at Waterloo in 1815, Britain had become the most powerful state in Europe, the prime architect of the victory over Napoleon and ruler of large parts of India.

Already, in the wars between 1689 and 1714, the British, with their allies, had defeated the previously unbeatable French armies of Louis XIV. This was made possible by the employment of the resources which the political settlement of 1689 had put in place. This settlement meant the King had to accept limitations on the power of the crown, in conjunction with a bill of rights, permanent parliaments and religious toleration, in return for finance for military operations. It brought into being the remarkably effective state financial apparatus (such as the Bank of England) that was to underpin Britain’s military success and commercial boom.

Foreigners emphasised that much of Britain’s prosperity was commercial; indeed that this was a distinctively commercial society. They noticed the flourishing ports, the exciting new turnpike road network, and impressive canal system. This was a country of trade, traffic and movement. An 18th century German pastor who walked round England, said, with evident feeling, that the country was ‘a land of carriages and horses.’

Commerce and affluence were intertwined. In 1763 Casanova (an interesting social commentator, not just a famous lover) noted ‘the general cleanliness, the beauty of the country and the excellent cultivation, the nourishing quality of the food, the beauty of the roads, and of the post chaises, and the reasonableness of the prices they charged, … the speed of the post horses, although they only went at a trot, finally the construction of the towns from Dover to London, such as Canterbury and Rochester.’ Britain seemed exciting, shiny, busy and rich.

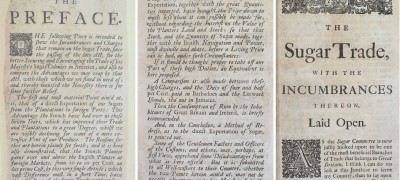

Georgian industry was thriving too. The 18th century was acclaimed as ‘an age of manufacturers’. For centuries the only product the English exported on any scale was wool; the only commodity that was remotely competitive on the international market. Domestic manufactured goods were mostly poor quality, inferior to the luxuries of France, Germany and Italy. However by 1750, the British could now manufacture a range of products to the highest European standards of technique and design: cottons in Manchester, ribbons in Coventry, boots and shoes in Northampton, wool and worsteds in Leeds, Bradford and Halifax, soap and glass in St Helens, steel in Sheffield or metal goods in Birmingham. ‘The most common trades here seem to partake of the perfection of arts’, noted the Abbé le Blanc in 1737. ‘With regard to the neatness and solidity of work of all kinds they succeed better in the least towns of England than in the most considerable cities of France.’ The term ‘manufacturing town’ was coined in the 1750s. The manufactories of Birmingham and Manchester were places considered so remarkable that they deserved to be visited by rich tourists.

The British saw themselves as a polite and commercial people. Most foreigners were struck by the affluence, vivacious commerce and great manufacturing capacity of the Georgians. It was Napoleon who first called the British a nation of shopkeepers, not Hitler. It was the Georgians who ushered in the first modern, industrial society.

Amanda Vickery is the author of ‘Behind Closed Doors At home in Georgian England’

External links

The National Archives’ Georgian Pinterest Board

British Library collection of articles on Georgian Britain

British Library collection of sources on Georgian Britain

BBC collection of articles by historians on various aspects of the period

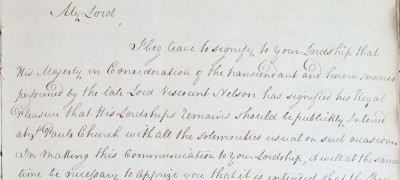

The Georgian papers: a new resource including digitised letters, diaries, account books and records of the Royal Household dating from the reigns of George III to William IV

Related resources

Jacobite Rebellion 1715: rebels with a cause?

Jacobite Rising 1745: A serious threat to the Hanoverians?

Family tree of the House of Hanover

Back to top