Download documents and transcripts

Teachers' notes

Using original sources in the classroom

Historical enquiry is central to the content of the National Curriculum. For pupils to develop the skills of enquiry, they need to see how primary sources are used to make historical claims, and grasp how and why contrasting interpretations of the past have been constructed in order to move away from the notion that historical study means learning a list of dates, people or events. Pupils should be encouraged to ask questions, think critically, weigh evidence, sift arguments and reach conclusions. It is also hoped that they will make connections through studying contrasting periods of history and to help develop a sense of historical perspective.

Primary school pupils may not understand that original sources provide the foundation for understanding about the past or that any interpretation can vary according to the sources studied.

To help introduce your pupils to the concept of primary sources, you could ask them to bring into class a collection of sources that help tell their own history: photographs showing them as a baby or toddler, copy of a birth certificate, birthday card, an old toy, first school /nursery report, holiday snaps, video clips and so on. This will help children grasp the fact that a primary source comes from the particular time period and is evidence of the past. Therefore, for historians, this could be an eyewitness account, diary, photograph, letter, poster, report, painting, seal, or cartoon.

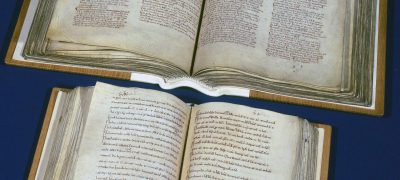

Again, many pupils may be used to reading or sharing narrative history textbooks which use sources purely used as illustration. In order to get them to think more historically it means getting them to look at the source as a thing in itself. Therefore it is important to provide the opportunity to study an original document (or good copy of one) rather than an extract or let them study an original photograph or seal rather than a modern day artist’s illustration in a book.

To engage your groups with original sources use clear prompt questions to help them evaluate them and draw out inferences. What type of source is it? (Photograph, picture, letter, poster, seal, report); Where is it from? Who is it for? When was it created? Interrogation of the nature of a source in this way will help them to develop lines of enquiry and encourage them to draw their own conclusions.

Learning to interrogate sources will help build pupils’ historical vocabulary and understanding that we find out about the past from these sources. In some cases, we have provided two sources per ‘significant person’ to show the value of looking at more than source and provide opportunities for further source comparison. All text sources have transcripts and simplified transcripts where appropriate to support pupils.

Layers of an onion

Working with sources is like exploring the layers of an onion. The first layer, ‘What is said/shown’ (photograph/cartoon/pictures) can provide information. However pupils need to be encouraged to delve more deeply into the other layers of the source onion. ‘How are things being said/shown?’ (Photographs may be posed in particular fashion, paintings idealised, the creator’s purpose evident).

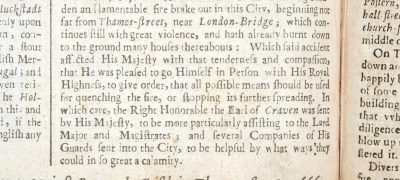

Understanding the type of a source and its context is central for unlocking its meaning and prevents pupils from taking it at face value or dismissing it as useless or ‘boring’ because it does not provide enough information. For example if the class is examining the poster in this collection about commemorating the Battle of Britain, they need to consider the language and imagery used in the poster but also ask why a poster, and not some other kind of source has been used to convey this information.

Extending the range of sources for consideration on the same subject can help to provide more context and widen the level of enquiry and historical understanding. As result pupils will appreciate that some sources are more helpful for different enquiry questions and sources can be checked against other to help them in their evaluation. Again, if a caption is provided within an original source, especially for a photograph or cartoon, discuss with your pupils if it adds to their understanding. To make a point about the use of captions, you could even change a caption of a given source and discuss how you have used the caption to alter the meaning of a source.

Tasks

Activity 1

Select any ‘Significant event’ source

Use the prompt questions available for download when you are working with your chosen source. [Print out questions or divide them up and write onto cards so that pupils can work in pairs. Use print outs of the source from the website or a projection of it on a whiteboard. Young pupils may need further prompting and support to address the later questions.]

Note: Most of these questions can be applied to any type of primary source. The first four questions concern the process of identification of a source and the later process of interpretation.

- What type of document is it? (photograph, letter, illustration, poster, map)

- Who produced it? Do you know anything about the author/creator?

- When was it written/produced?

- When looking at text sources can you explain meaning of any key/difficult words

- Why was the source written/made?

- What is the source saying/showing about this event?

- Does the source relate to a particular historical event?

- How reliable is the source and does it have any limitations?

- How similar or different is this source to others from this period about this event that you may know about? If so, can you explain why?

Activity 2

- Divide the class to look at different history text books on a particular event

- Can the pupils find other historical sources on their significant event?

- Can the pupils discover if the text books support anything they have learnt from the original sources in this collection?

- Do their textbooks tell them anything different/new about the significant event?

- Can the pupils find any more primary sources about their significant event on The National Archives Education web site?

- Now to take your investigation wider, compare one event, another event from a different time and explore through further discussion and research the differences between aspects of life in each period.

Further practice with historical sources:

Go to Start Here in our website called The Victorians and get help from our two video presenters about different types of sources for the Victorian period. The video introduces the concept of sources and is followed by a starter activity using a Victorian photograph modelling a useful questioning technique.

Finally, all of our searchable online lessons are categorised according to this National Curriculum focus which is recorded in the ‘Lesson at a Glance panel’. We hope this will flag up further useful primary sources and related lesson activities for teachers when approaching this topic.

Introduction

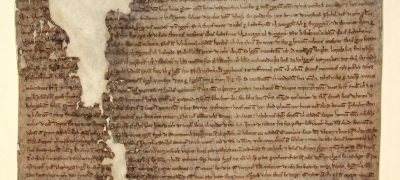

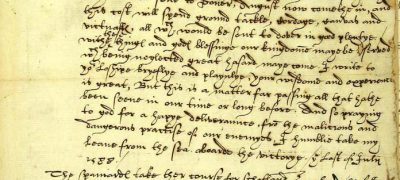

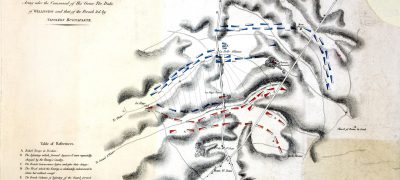

From the sealing of Magna Carta, the coming of the Armada, the Great Fire of London, a Christmas ceasefire on the Western Front in 1914 to Decimalisation in 1971, this selection of sources, based on records held at The National Archives, can be used in the primary classroom to support the National Curriculum element ‘significant events’ beyond living memory. The collection is by no means exhaustive, but contains some of the popular choices and other suggestions for teaching this topic. We hope to add to the collection over time. In addition, we have provided links to other useful resources for ‘significant’ events.

The sources can be used within any scheme of work which is based on developing a sense of chronology where pupils can see that a particular ‘significant event’ fits into a time frame. Again working with sources in this way will help pupils to register similarities and differences between aspects of life between periods, for example comparing the Great Exhibition of 1851 with the Festival of Britain in 1951. Other ‘events’ sources can be used to consider questions of what we are remembering and why? Have things always been the same? Why have some things changed?

Back to top