This series takes you behind the scenes of 20sPeople – a season of exhibitions, activities and events from The National Archives that explores and shares stories connecting the people of the 1920s with us in the 2020s.

Once British Always British is a collection of three audio dramas exploring the experiences had by those who came to Britain in the 1920s from elsewhere in Britain’s empire. All the plays are based on true stories found within the files at The National Archives.

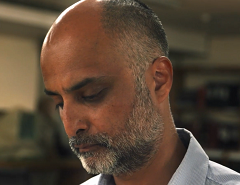

Iqbal Singh, Regional Community Partnerships Manager

We spoke with Iqbal Singh, Regional Community Partnerships Manager here at The National Archives, about the project, its impact, and the power that personal experiences have in bringing history to life.

Tell us a bit about the project and how it came about.

Once British Always British is based upon research I’ve been doing on seafarers in the 1920s who came to Britain from Yemen, India, and the West Indies.

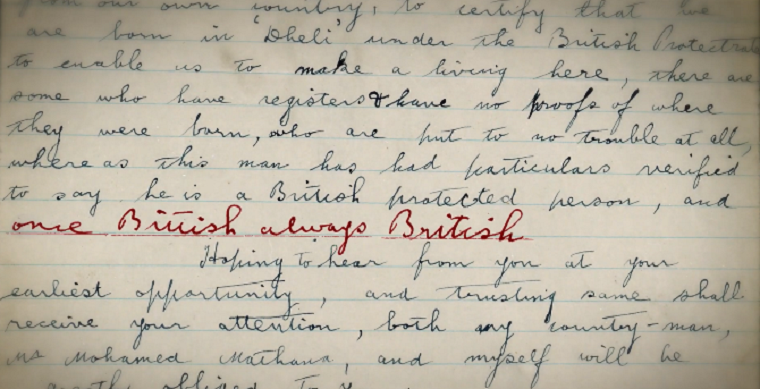

We have a collection of records of them applying for a Certificate of Nationality, which came into play in 1925 when the ‘Coloured Alien Seaman’s Order’ was brought in, requiring any person of colour to prove their right to be living and working here. It created quite a lot of tension – these men were coming from the British Empire and they considered themselves British, yet here they were confronting this obstacle of proving their nationality.

One of the men whose story featured in the audio dramas wrote into the government saying ‘once British, always British’ – that’s where the title came from, it seemed so fitting.

I had already done a project working around theatre and archives and it seemed like a brilliant opportunity to bring drama into our 20sPeople programme.

What is the aim of the plays?

The plays are really opening up history and archives by making audiences want to find out more about these stories – the stories told are ones that bring humanity and the warmth of people to the forefront. It makes people want to find out about the 1920s and what life was like.

People may not think that there were many people from the Caribbean or other parts of the empire in 1920s Britain, but there were. The hope is to present diverse experiences of 1920s Britain.

How did you find the stories?

My role in the Outreach team at The National Archives is to get these types of projects going – I have experience of how drama works with history and so that has become a large part of my role. I do a lot of the research so that the writers have a more concentrated brief.

How do you think theatre widens the reach of archival engagement?

We’re wanting to do more regional work in the key communities where these men were living: Liverpool, Cardiff, South Shields. The key is to make our collections more relevant to people who may think that there is nothing in our collections about them.

For those whose great-grandparents, grandparents, or even parents weren’t born here, they often find that there is a lack of family history that they can easily source or connect to. In this case, looking through our collection, they could find someone with a similar name to theirs – that might inspire further research.

That’s how I initially got engaged in history – I discovered there were Indian soldiers fighting in the First World War. Even though I cannot trace anyone in my family who fought, the fact that these men and their families were making sacrifices and contributions was really important.

How do you think these plays give voices to those who would not necessarily have been heard?

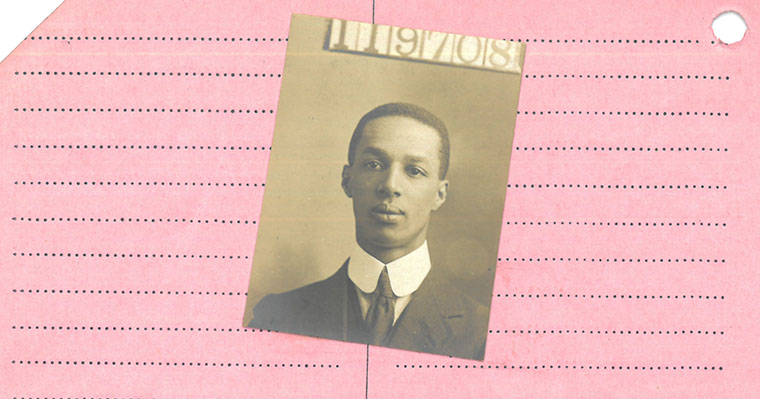

The records we have are often one sided, for example an interview with an official can lose that person’s voice. We don’t really know the day to day life of these men, so drama can really help fill in the gaps. A Stranger in a Strange Place provides the opportunity to look at West Indian sailors, and gives a voice to Claudius Smart, as opposed to the officials making the records.

Claudius Smart’s identity card

We were also really keen to bring in women’s voices. Steam Rises brought in voice of the seaman’s wife through imagined letters and The Fireman included the voice of the seaman’s great granddaughter.

Why do you think that fiction is so powerful as a form of interpretation?

People love stories about people, it’s very simple. History can only give you so much, but to get people excited and interested you need them to get involved with the character.

For example, quite a lot of these men would stay with innkeepers and landladies; in Steam Rises, Satinder Chohan imagined a love affair between the landlady and the seaman. That’s something that certainly isn’t in the records, but it brings the whole story to life.

People may not be personally interested in the 1920s, but if they hear a story about a love affair between an Indian man and an English woman and how they met, they might want to find out more about the period with that story as a baseline. They might start with a drama, leading to them ordering a book or coming to The National Archives – it snowballs.

What are the benefits of using audio as a creative medium?

Firstly, it has been great during the pandemic! We can stream it online and it really allows you to imagine – in ways it can be more powerful than stage or screen.

A big plus is that you do not have to be free at a certain time in a certain place in order to experience it. With both digital and audio, the recording is there for you to listen to at your leisure – it’s much more accessible.

Our link with Tamasha is really important and has meant we can get the most out of the medium as possible – they have the resources and skills we’d need as producing audio drama is a lot of work.

What were the challenges of making plays like this from original records?

One of the biggest challenges is to imagine the story in a convincing way and not to get carried away. It’s key to keep true to the period – the writer and us at The National Archives need to spend quite a bit of time making sure the drama is historically accurate. For example, we can’t have working class people in the 1920s eating burgers, they should be eating something like porridge made with water instead. A record will tell you that there was an Indian man who has arrived in Cardiff. But we want to know, what kind of place was he leaving? What was the place he was going to like? What were the sounds? A lot of digging goes into these projects in order to create a sense of realism, it is really key to get the little details right.

Another challenge is finding writers and a company to collaborate with that can do justice to the project – we want to be working with those who really want to tell this story. Ideally the dramas are written by someone with a shared background – it’s not always the case, but they can bring some inflections, language, cultural points that can add a lot. In A Stranger in a Strange Place, the writer, Mel Pennant, having a link to the Caribbean and Claudius’s story brought a lot of depth to the writing.

How important is it to have stories of people from different places?

Delving in to specific stories allows you to really bring out the nuance of individual experiences. We don’t want to put people into one box when people have such different experiences depending on where they have come over from.

For people from the Caribbean, English is their first language so their stories and interactions are different. The empire operated differently in different parts of the world – I think that is part of what we have been trying to explore.

Yemeni and Caribbean men were allowed to live here, so many of them formed relationships and became part of their communities, whereas the Indian men ‘jumped ship’ and weren’t actually allowed to work from here. Their experience was often more precarious, so this massively informs their story.

How would you suggest people find out more about this subject if they’re interested?

The 1921 Census is really important. Many of these men do feature and as their occupation is present you’ll often find references to seamen, as well as boarding house keepers.

We have other records in our home office files and colonial office files, as well as there being specialist museums and regional archives that have more information.

Findmypast have lots of other records about people from Britain’s empire and Commonwealth that illuminate these stories, and not just in the 20s – you can follow these stories through into the 30s, 40s, and onwards.

Find out more

Watch the Making of Once British, Always British film to hear from the playwrights about the making of all dramas in the project.

Steam Rises by Satinder Chohan tells the story of Buhur – one of the many Indian men employed to shovel coal below decks on merchant navy vessels.

The Fireman by Hassan Abdulrazzak is told from the perspective of Sahar, who goes to London to investigate the truth about her Yemeni great grandfather, Ali Abdul, and his early days in the UK.

A Stranger in a Strange Place by Mel Pennant documents the experience of Claudius Smart, a merchant seaman who came to the UK from the British West Indies, and details how doors were closed to him due to his marriage to a white woman. Read more about Claudius Smart’s story in this blog article.