What did paupers say about the Poor Law?

Students and teachers can discover the voices of the poor who wrote to the Poor Law Commission and explore how they understood, experienced and exercised agency under the New Poor Law from 1834.

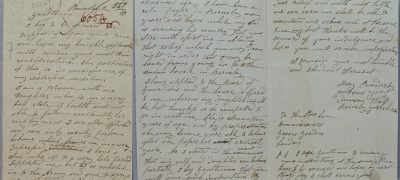

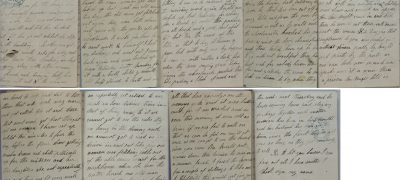

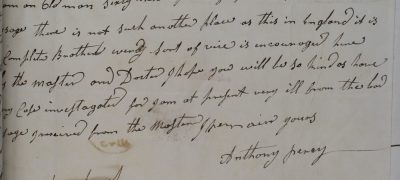

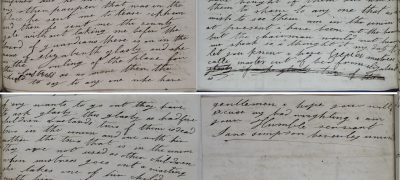

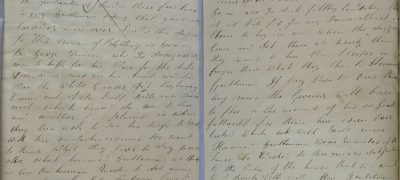

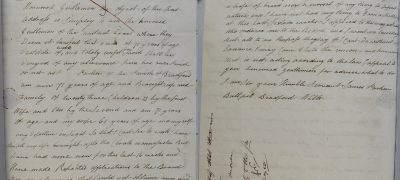

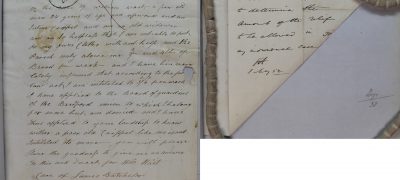

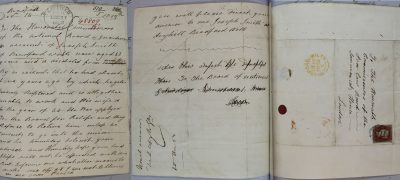

This collection of documents represents a small sample of the letters that have been identified and transcribed as part of ‘In Their Own Write’, an Arts Humanities Research Council funded project, 2018 to 2021, which uses letters from paupers and other poor people, and other material such as petitions, sworn statements and advocate letters written on behalf of paupers to investigate the lives of the poor between 1834 and 1900. It is run jointly by The National Archives and the Department of History at the University of Leicester.

The majority of work focuses on the thousands of volumes of poor law correspondence (MH12) held by The National Archives much of which has been little used by historians.

Teachers' notes

This document collection includes letters written by the poor and paupers to New Poor Law officials after 1834. It allows students and teachers to develop their own questions and lines of historical enquiry on the nature of the legislation, the role of the authorities and the impact of the law on those who experienced it first-hand. The collection offers a unique insight into this world with these documents available digitally for the first time.

To begin with, ask your students to look at the short quotes shown on the document web page. Can they detect any key themes or issues? For further context, read the introduction to this collection and highlight the main points. You could also do a Google search for workhouse images, or find out about a local workhouse in your area if one exists.

Now read a sample of these letters. We have included a modernised transcript in terms of spelling and punctuation. Here, some words have been defined within the text using square brackets. We have also in some cases included transcripts for the notes made on the original letter by the Poor Law Officials who received it, providing insight into how the officials responded and how the bureaucratic system worked. As the students become familiar with their content, discuss the following questions in pairs or groups:

- What issues or complaints are the writers raising with the Poor Law Commissioners?

- Who wrote on behalf of the poor in letters? Why do you think they were motivated to do so?

- For what reasons did people find themselves in the workhouse?

- Were men and women treated differently?

- What work did paupers have to do inside the workhouse?

- What was the purpose of this labour do you think?

- Is there evidence of medical treatment received in the workhouse?

- What can we infer about diet in the workhouse?

- What evidence is there that some letters were concerned about corrupt the workhouse officials or the Board of Guardians?

- How did the Poor Law impact on families, children and the elderly?

- How did the Poor Law Commission respond to these letters?

- What can we infer from the language and tone used in these letters?

- Why did some people request ‘outdoor relief’ rather than ‘indoor relief’ or admission to a workhouse?

- Were any writers in favour of the Poor Law system?

- What do these letters reveal about the causes of poverty at that time?

- What general conclusions can students draw from considering this group of documents as a whole? How could study of the topic be extended?

- Write your own version of a couple of letters and compare with a partner. What does this process reveal about the nature of historical interpretation?

- Compare and contrast a selection of letters covering similar topics.

- Many people are familiar with Charles Dickens’s novel, Oliver Twist containing scenes inside the workhouse. How accurately does it compare to the content of these letters?

It is hoped that these documents will offer students a chance to develop their powers of evaluation and analysis concerning aspects of poverty, pauperism and social reform. How does Poor Law legislation fit into a study of the development over time of the welfare state in Britain? They might consider how this has been interpreted in debates between historians and social scientists.

Finally teachers could also use the collection to develop their own resources or encourage students to ‘curate’ their own ‘exhibition’ of the most significant sources on the topic. Please note that some sources may contain sensitive material so use with care.

Audio files have been added to the resource to enhance engagement with the documents. We have created an interactive map to show the location of each letter with its particular Poor Law Union and county.

Connections to the Curriculum

Key Stage 3

Ideas, political power, industry and Empire: Britain 1745-1901: party politics, extension of the Franchise and social reform.

Key Stage 5

AQA:

- Industrialisation and the people: Britain, c1783–1885: Political change and social reform, 1832-1846

Edexcel:

- Britain, c1785–c1870: democracy, protest and reform: Poverty and pauperism, c1785–c1870

- Poverty, Public Health and the state c1780-1938: Aspects in depth, poverty, the people and the poor

OCR:

- From Pitt to Peel: Britain 1783—1853

Introduction

Dr Peter Jones, Research Assistant, ‘In Their Own Write: Contesting the New Poor Law, 1834-1900’, The University of Leicester.

The question of what to do with the poorest members of society is one that has exercised human communities for as long as those communities have existed. All the major religions teach compassion and encourage charity towards the poor; but by the early-modern period in Europe, population increase and a gradual move towards urbanisation, meant that local piecemeal responses were no longer sufficient to contain the growing problem of poverty. In England and Wales, the response was to establish a set of national regulations in the 16th and 17th centuries that required local communities to look after their own poor (the ‘Old Poor Law’). The so-called ‘deserving poor’ (that is, the elderly, widows, orphans, the sick and disabled) were given ‘relief’ in money or goods. Those who were thought to be less deserving – in particular, the ‘able-bodied’ poor who, it was thought, should be able to look after themselves – were put to work for their relief. This system of welfare was administered at the level of the parish (which commonly overlapped with a village or township) and it continued in place until the early-19th century.

By the 1830s, however, as the population rocketed and urban poverty became endemic, the rising cost of relief alarmed large ratepayers and those who governed England and Wales. The response of the authorities was (as it very often is) to drive down costs by deterring people from seeking relief in the first place. In 1834 the Poor Law Amendment Act was passed, ushering in the New Poor Law which, in theory at least, made the welfare landscape a much less hospitable place. Poor relief would now be administered by local boards of guardians, who oversaw whole groups of parishes (known as ‘unions’), and instead of money and food being given to paupers in their own homes unions were given the right to place their poor in local workhouses; large prison-like institutions where families were separated and individuals were required to perform hard labour for meagre rations. Unsurprisingly, the new system, and particularly the workhouse, was hated by many paupers. Not all paupers were sent to the workhouse (most were not), however most of the so-called ‘deserving poor’ who were given relief in their own homes often felt that it was completely inadequate for their needs.

The Central Authorities and Pauper Letters

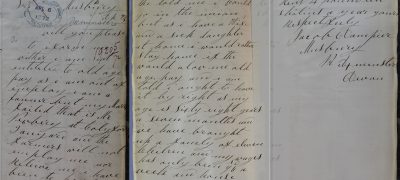

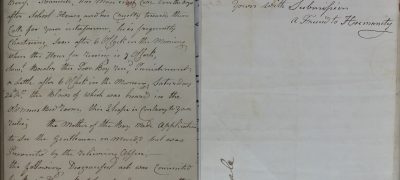

Sometimes, paupers felt so aggrieved at their treatment that they wrote to the central poor law authorities in London to complain. The Poor Law Commission was set up in 1834 to ensure that relief was administered properly under the New Poor Law. Its main focus was on ensuring consistency of practice in unions across England and Wales, but paupers soon realised that if they had a complaint about ill-treatment or the rules being broken by local officials then the Commission ought to do something about it. Many such complaints were received between 1834 and 1900 by the Commission and the bodies that succeeded it (the Poor Law Board in 1847, and the Local Government Board in 1871), and these were bound up volumes along with all the other correspondence received by the Commissioners. These volumes are now held at The National Archives, and there are more than 16,000 of them in total!

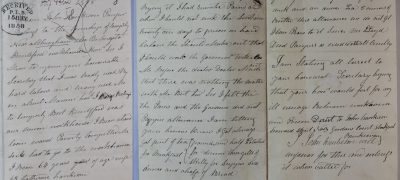

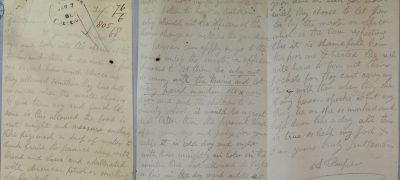

As you will see from the letters in this sample, paupers complained about all kinds of things; but there are some broad themes which it is useful to tease out. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the most common complaints were about the workhouse. In particular, paupers felt that they should not have to go there in the first place when their only ‘crime’ was poverty. Many in our sample complain that the relief they were given in their own homes was either inadequate, or was reduced or stopped altogether, so that their only alternative was to become an inmate in the ‘house’. Others complained bitterly about the treatment they received once there, whether it was the terrible food, the appalling living conditions or the arduous work. A large proportion of the letters come from those who were traditionally considered as the ‘deserving poor’: the elderly, young widows with children, and the sick or disabled, who felt that they deserved different treatment from the able-bodied, or ‘idle’ poor.

Sometimes, the letters reveal really terrible treatment, beatings or abuse by the officials and other paupers; and taken together it is easy to conclude (as many historians have done) that the New Poor Law really was an inhuman and cruel system. But it is important to remember that these letters are a ‘self-selecting’ sample; that is, paupers rarely wrote to say what a fine time they were having in the workhouse, and how generous the master and matron were (although there are one or two examples of more positive letters, even here)! But despite this note of caution, the one thing that comes through loud and clear in these letters is the voice of the paupers themselves, and the multitude of fascinating stories they had to tell.

External links

In Their Own Write https://intheirownwriteblog.com/

Voices of the Victorian Poor – 3500 pauper letters mapped to their origin points showing a snapshot of life across the country https://www.victorianpoor.org

Find out more about Charles Dickens, his experience of poverty and purpose in writing his novel Oliver Twist. https://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/oliver-twist-and-the-workhouse#

Workhouses: The story of an institution. https://www.workhouses.org.uk/

Beneath the surface: A country of two nations https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/victorians/bsurface_01.shtml

The ‘In their own write’ project, show casing more pauper letters 2020 https://blog.nationalarchives.gov.uk/in-their-own-write-three-million-words/

The ‘In their own write’ project, show casing more pauper letters 2015 https://blog.nationalarchives.gov.uk/paupers-life-words/

Why did people fear the Victorian workhouse? webinar https://media.nationalarchives.gov.uk/index.php/webinar-people-fear-victorian-workhouse/

Back to top

1834 Poor Law

What did people think of the new Poor Law?Voices of the Victorian Poor

Resources from the Teacher Scholar Programme