Teachers' notes

This document collection allows students and teachers to develop their own lines of historical enquiry or historical questions using original documents on this period of history.

Students could work with a group of sources which identifies different themes – for example, loyalty, bravery, motivation, radicalism or sedition within the Indian army. They also could consider how the experience of the Indian army affected imperial relations or assess the contribution of the Indian Army to the First World War. We hope that the breadth of the collection allows such flexibility and offers students the chance to develop their powers of evaluation and analysis and support their course work.

Also, teachers can use the collection to develop their own resources or encourage students to ‘curate’ their own ‘exhibition’ of the most significant documents on the topic.

Finally, students may consider film sources as interpretations of the First World War in relation to these documents by following the link to Pathé provided here.

Connections to the curriculum

These documents can be used to support exam board specifications on the history of the First World War

AQA GCSE History

Wider world depth studies, Conflict and tension 1894-1918

Part two: The First World War: Western Front

OCR GCE History A level

Unit Y218: International Relations 1890-1941

Key topic: The causes and nature of the First World War

National Curriculum for History Key Stage 3

The First World War and the Peace Settlement

Introduction

When war broke out in 1914, as part of the British Empire, India rallied to the support of Britain. Over 1.4 million Indian soldiers and non-combatants served in the war, including on the Western Front. Before 1914 a ‘colour bar’ to uphold British prestige was in force, preventing Indian troops from fighting against a ‘white’ enemy. In this context, the First World War marked a significant departure in imperial relations.

Recruited from the ‘martial races’ and trained in frontier warfare, the Indian Army – the largest volunteer force in the world – was in no sense a modern army prepared for the industrial warfare of the Western Front. How did they respond? Did they discharge their duties with their traditional fighting qualities and loyalty or were there dissenting voices? What led to dissent and how widespread was it?

About 138,600 Indian soldiers saw action on the Western Front. They took part in major battles at Ypres, La Bassée, Festubert, Neuve Chapelle, Loos, Somme and Cambrai. They suffered heavy casualties, fought with courage and won eight Victoria Crosses on the Western Front out of a total of 11 awarded during the First World War. Sir Walter Lawrence (Commissioner for the Welfare of Indian troops) concluded: ‘it was a bold experiment to bring them to Europe … it seems to have succeeded.’ However, some British Army Officers considered the Indian Corps to be a failure.

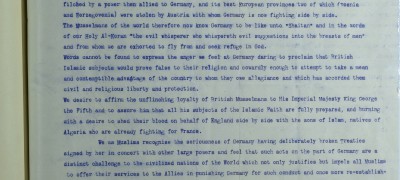

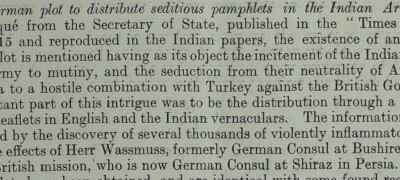

Indian soldiers themselves took pride fighting in a ‘white man’s war’ to prove themselves equal. Their letters show genuine expressions of loyalty and prayers for British victory. For Indian soldiers family honour and ‘izzat‘ was bound up with military tradition. Despite this, their letters also reveal some expressions of dissent. As war dragged on and casualty figures mounted, some felt that Indians were used as cannon fodder. They urged potential recruits not to enlist for service in Europe. When the wounded were sent back to the trenches this caused much unhappiness as this was seen as non-contractual and there were petitions about this, even to the King. Their rate of pay, 11 Rupees per month, became another reason for discontent and was raised to 20 Rupees by the last years of the War. Lack of leave caused homesickness, leading some to feign illness or use Indian herbs to induce sores. However, from the evidence it is clear that desertions were few, dissent never became mass rebellion and recruitment in India was not affected. Even when the most important Muslim state, Turkey, became an ally of Germany, British Muslim soldiers stayed loyal to the Empire and disregarded German propaganda.

To secure their collaboration, the imperial state manipulated traditional Indian soldierly qualities for King and Empire. This is also evident in Europe from official pronouncements praising their gallantry, the organisation of hospitals on caste and religious principles, and the setting up of a burial ground for Muslims near the Woking Mosque while Sikhs and Hindus were cremated at Patcham (in contravention of the 1902 Cremation Act). But there was a limit to how far British prestige could be compromised, even for political reasons.

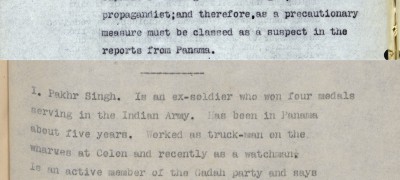

The years before 1914 had witnessed unrest both in India and among Indians in Europe and the USA. In 1907, Madame Cama had unfurled the tricolour at a Socialist Conference in Germany while Madan Lal Dhingra assassinated Sir Curzon Wylie in London. Although Indians enthusiastically pledged support for the war, pockets of radicals caused anxiety: it was feared that seditious literature would be smuggled into Europe to undermine the loyalty of the troops. A special Censor’s Office was set up at Boulogne to monitor morale and check for letters and literature showing signs of dissent. Radicals in the USA, like Har Dyal and the Ghadar Party, were kept under strict surveillance. They aimed to stir up Indian soldiers against the British with their publications, fiercely critical of British rule. The actual amount of seditious literature proved to be negligible and the Indians remained loyal.

Concepts of loyalty and dissent are complex issues as these documents reveal. Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon’s First World War poems are a case in point.

The First World War marked a turning point in imperial relations. It was accepted that the Indian army needed reforms. Did the Indian contribution in the war hasten the process of decolonisation? There is no easy answer. The Montague-Chelmsford reforms fell far short of expectations. The Rowlatt Acts of 1919, the massacre at Amritsar and martial law brought repression rather than the promised reforms. However, the soldiers’ experience of Western society widened their horizons and created new aspirations.

Rozina Visram

Author of ‘Ayahs, Lascars and Princes: Indians in Britain 1700-1947’ (1986)

and ‘Asians in Britain: 400 Years of History’ (2002)

Glossary

India or Indians: this term is used to refer to British India (1858-1947), comprising present day India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Burma.

‘Martial Races’: Based on the theory of ‘martial races’ the Indian Army, recruited from the peasant classes, was drawn from a narrow ethnic and geographical pool mainly from northern and central India, the North-West Frontier Province and Nepal. These ethnic groups were considered to be ‘naturally more warlike’. The theory of ‘martial races’ raised their profile as the ‘chosen warriors’ leading them to enlist with enthusiasm.

Izzat: honour, prestige or absence of shame.

Cannon fodder: belief that certain groups of soldiers were used more than others in battle; in this case Indian soldiers felt that they were sent to the trenches ahead of the white soldiers.

Tricolour: Literally three colours. In this context the colours were green, yellow and red, the proposed Indian national flag.

Montague-Chelmsford reforms: 1917-18. The reforms outlined proposals for an increased representation of Indians in the Government of India.

Rowlatt Acts: 1919. Named after the High Court Judge, the Act gave the police wide powers to decide which offences amounted to a conspiracy against the Government. It also provided for speedy trials, not by a jury, but by special tribunals. Those suspected were denied representation by a lawyer; there was no right of appeal.

Amritsar Massacre: 1919. A peaceful, unarmed crowd of men, women and children, gathered for a protest meeting at Jalianwala Bagh were fired upon by the order of the military commander, General Dyer. 379 died and 1,200 were wounded. Ironically Amristar province had contributed the highest number of men for the First World War.

Cremation Act 1902: By this Act cremation could only take place in a crematorium of which notice had been given to the Secretary of State.

Additional Notes

Madame Cama: Bhikaji Rustom Cama was influenced by the India House Revolutionary Movement based in Highgate, London. She settled in Paris after 1909 and edited the newspaper, ‘Bande Mataram’ (Hail Motherland). See The British Library, IOR: POS 6052, History Sheet of Madame Bhikaji Cama.

Madan Lal Dhingra: See The National Archives References: CRIM/1/113/1 and CRIM 10/99.

Further Reading

Rozina Visram: Ayahs, Lascars and Princes: Indians in Britain (Pluto Press, 1986; Routledge Revivals, 2016) Chapter 6 (Soldiers of the Empire in two World Wars).

Santanu Das: 1914-1918 Indians on the Western Front (Gallimard, 2014)

David Omissi: Indian Voices of the Great War Soldiers’ Letters, 1914-18 (Macmillan. 1999)

External links

Five short plays produced in response to these documents, relating to the experiences of people from South Asia at the time of the First World War. The series was created by five playwrights from the Tamasha Developing Artists (TDA) programme and funded by the Friends of The National Archives.

The ‘A Street Near You‘ project maps individual soldiers’ records to their homes, globally, allowing us to see who served in the war on a local level. The map includes records of soldiers who joined the Indian army.

‘Loyalty and Dissent’ article in the journal Paper Trails from UCL Press: https://ucldigitalpress.co.uk/BOOC/Article/3/119/

Back to top