This story is one of the winning stories in the 20sStreets competition. The competition invited entrants to research and share stories of the 1920s, searching for the most fascinating local history stories covered by the 1921 Census of England and Wales. There were six winning stories and twelve runners-up entries.

The Three Choirs Festival makes its BBC Debut

By Simon Carpenter, winner (one of five) in the Individual category

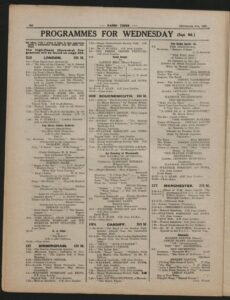

Radio Times, September 4 1925 Credit: British Newspaper Archive

September 1925. The BBC was just three years old. At over 200, the Three Choirs Festival, an annual week long classical music festival that alternates between Gloucester, Hereford and Worcester, was somewhat more established. The two came together for the first two times that month, and composer Frederick Delius, over 300 miles away in France listening on a neighbour’s wireless, was thrilled to hear one of his most famous works, ‘On hearing the first cuckoo in spring’ broadcast live from Shire Hall Gloucester. It was being performed by the London Symphony Orchestra under the direction of the Gloucester Cathedral organist and that year’s Festival director, Herbert Brewer.

They were by no means the only listeners. As well as the estimated million plus people who possessed their own wireless sets, and those who attended private parties, large crowds gathered around loudspeakers provided by local businesses during both broadcasts. In Gloucester these included Messrs L C Mitchell & Co at 52 Northgate Street, County Electrical & Wireless Stores at 86 Southgate Street, and the Radio Electric Company who had laid on three loud speakers at their shop in 3 Commercial Road.

The 1925 Three Choirs Festival

The 1925 Festival, of which the two broadcasts were a part, was undoubtedly the high point of Brewer’s career. Not only musically speaking, with more new works than ever before, including the premieres of ten new works including by Gustav Holst and Herbert Howells, the latter during the Wednesday broadcast. But there were also new peaks in both attendance (19,973), and receipts and profits from all sources amounted to £3,700. Overall 34 British composers, 25 of them living, were represented in the programmes and services. Fifteen, including Sir Edward Elgar and Ralph Vaughan Williams, conducted their own works. The two broadcast concerts were on the Wednesday and Friday evenings of the Festival week, and both were from Gloucester’s Shire Hall, which then included a 1,000-seater concert hall. Brewer had chosen varied music for both, and among the popular works by Mendelssohn, and Mozart among others – including Delius’s On hearing the first cuckoo in Spring – were modern works by Ethel Smyth, Herbert Howells, Gustav Holst, Granville Bantock and Brewer himself. Many were conducted by their composers, including those by Howells, Smyth and Bantock.

The first broadcasts from Gloucester

In fact these concerts were not the first time the BBC had broadcast from Gloucester. Earlier in the same year, short daily broadcasts were made between July 1st and 4th of various events taking place in Gloucester Park as part of a carnival organised to help raise £10,000 for Gloucester Royal Infirmary. The Company had been set up just three years earlier in 1922 as a consortium led by the larger than life Scottish engineer, John Reith, to coordinate existing local radio transmitters and establish new ones. The licence for users was introduced in 1923, the same year as the first ever outside broadcast, and both the Company and its number of ‘listeners in’ grew quickly.

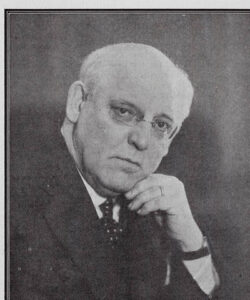

Percy Pitt, English conductor and the BBC’s Music Director from 1923 to 1930. Illustration from the BBC Year Book (British Broadcasting Corporation, London, 1930). Credit: Look and Learn

The BBC, most probably through its highly respected musical director, Percy Pitt, first approached Brewer early in 1925. Brewer responded by saying he believed it would be ‘prejudicial from a financial point of view’ to broadcast any of the cathedral concerts and suggested that the two secular concerts during the week could be covered instead as he did not believe their ticket sales would be affected. At this time concerts were held in both the cathedrals and, for music considered not appropriate for cathedrals, in local public halls. Brewer may also have suggested to the BBC that they broadcast the opening service in the cathedral, for at a Festival planning meeting in the January it was reported that the Dean and Chapter had refused permission for the opening service to be broadcast unless all the services during the week were also broadcast.

Brewer’s cooperation and support was unusual among concert promoters. At this time the BBC had no standing in the world of music, and was generally disliked by a strong minority of leading classical musicians, their various reasons included that broadcasting would discourage concert going, that the Company was just a mechanical music maker, and it was an enemy to artistic excellence. And by many it was just ignored as a popular toy. However, thanks largely to the diplomatic skills of Percy Pitt, the musical world was slowly being won over. It would have been Pitt also who granted the Festival the services of the BBC’s leading outside broadcast engineer, Captain A G D West and three assistants, on site.

Given Brewer’s support and cooperation it would be easy to draw the conclusion that he was being far sighted. But that has to be weighed against the testimony of his own son, Charles. In 1926, a year after these events, Charles was at a loose end, having tried several ‘careers’:

‘I asked my father, who had given some broadcast performances, to write to Mr J.C.W. Reith … and ascertain what hopes there might be of admission to the staff.’

He reports that his father’s initial reaction was ‘dubious … Broadcasting was then in its infancy. It was still a Company and not a Corporation. It was thought to be a “craze” – like roller skating, diabolo and paper bag cookery had been.’ So Brewer, despite outward appearances, was actually in the ‘popular toy’ camp.

Strong tonic to keep my nerves steady

Brewer later shared his thoughts on his first broadcast experiences with the Gloucester Journal:

‘never before had I conducted a concert with so large an audience, which must have numbered hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions, and not only in this country but throughout Europe. The feeling was an uncanny one when I took my stand at the conductor’s desk with a microphone either side of me. I was well aware that whatever I did would be instantly broadcast, and my last word of caution was to warn the members of the orchestra to be careful in their choice of language should a string break! It is rarely I feel ‘nervy’ when conducting, but I confess that on these occasions I felt I wanted a strong tonic to keep my nerves steady: there was a feeling of awe which unsteadied one, a feeling thar is impossible to put into words.’

Unfortunately one member of the orchestra forgot the warning:

‘After the performance of Dame Ethel Smyth’s brilliant overture The Wreckers under the composer’s direction, Mr Reed [Billy, the ever-ebullient leader of the orchestra] exclaimed, as she was walking away from the desk, ‘Bravo.’ [This] was heard distinctly in Sussex!’

A better show had never been broadcasted

During the concert, one time when he wasn’t required to conduct, Brewer ‘descended to the operating-room occupied by Captain West and his assistants to listen … Captain West was in continuous telephonic communication with London and Daventry whilst his assistants were at the machine. He was constantly giving orders as to what was to be done and what not be done … Whilst I was there a telephone message from [John Reith] came through saying that a better ‘show’ had never been broadcasted, and that the transmission was perfect.’

After the Wednesday concert Brewer was disappointed to learn that the programme had overrun and so the radio listeners had not heard the last item. On Friday he tried to remedy this by, ‘pushing on and cutting out the interval, but the pace was too great for the authorities at the other end, and a ‘phone message soon reached me through Captain West with a request that I should go ‘slow’ and give them breathing space. I have since heard that the ‘announcer’ in London had barely time to say what the next number would be before it was being performed.’

Letters of thanks

In the days following, Brewer received many letters of thanks from all parts. A church Rector told him:

‘the transmission was perfect, and … it was quite remarkable how the listeners-in at the Rectory seemed to get the atmosphere of the room and to feel as it were how each item was being received by the audience in the Shire Hall.’

They also apparently appreciated that they could clearly hear ‘applause and cheering, the tuning of violins, and conversation amongst members of the audience during a slight delay.’ Brewer also heard from a composer, Howard Carr, who told him that where he was on holiday:

‘there were hundreds of people listening to a loud speaker on the Wednesday, and every note came through. They were particularly struck by the brilliant singing of the Chorus…while I was walking here to-night (Friday) I heard the first bars of your suite … on a loud speaker in a little tea house. It was so enchanting that under cover of a much unwanted cocoa I heard it through. The choir transmitted excellently, the orchestration was particularly lucid, and the performance seemed to me the best I have heard through this medium.’

Sources

Primary

- British Newspaper Archive (https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk)

- BBC Programme Index (https://genome.ch.bbc.co.uk)

- Brewer, Charles, The Spice of Variety, Frederick Muller (1948).

- Brewer, A. Herbert, Memories of Choirs and Cloisters, Stainer & Bell (2015).

- Delius, Frederick, A Life in Letters Volume 2, Scolar Press (1988) (Accessed via web).

- Grand concert at the Shire Hall, Wednesday evening, September 9th 1925. Book of the Words. (The programme for the Wednesday evening broadcast).

- Lee Williams, C., Godwin Chance, H., Hannam-Clark, T., Annals of the Three Choirs of Gloucester, Hereford and Worcester. Continuation of History of Progress from 1895 to 1930, Minchin & Gibbs (1931).

Secondary

- Boden, Anthony & Hedley, Paul, The Three Choirs Festival: A History, Boydell Press (2017).

- Chamier, J. Daniel, Percy Pitt of Covent Garden and the BBC, Edward Arnold & Co (1938).

- Hendy, David, The BBC a Peoples’ History, Profile (2022).

- Matthews, Geoff, The Creation of Production Practice in the Early BBC with Particular Reference to Music and Drama, University of Leicester Phd thesis (1984).

The rest of the winning and runners-up stories will be published on our 20sStreets portal in the coming weeks.