This story is one of the runner-up stories in the 20sStreets competition. The competition invited entrants to research and share stories of the 1920s, searching for the most fascinating local history stories covered by the 1921 Census of England and Wales. There were six winning stories and twelve runners-up entries.

Running Away to Join the Brickworks

By The Brickworks Museum, runner-up (one of three) in the Group category

Content note: This article contains language quoting original documents from the early 20th Century that contain racist language and ideas. This article also contains graphic description of injury inflicted by animals. The original wording has been preserved here to accurately represent the records and to help us understand the past.

It is customary, in times of stress or ordeal, for the English to joke about running away to join the circus. This story, John Honton’s story, stands out as he did quite the opposite – leaving the circus to join the Bursledon Brick Company in 1902.

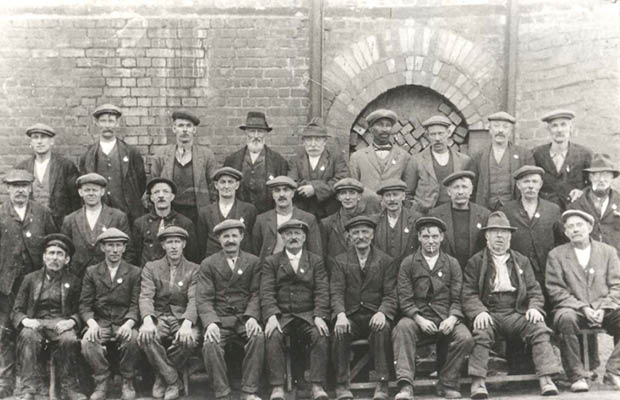

Photograph of brickworkers for the Burlesdon Brick Company, outside of kilns, featuring John top row, fourth from the right. Source: the archives of the Brickworks Museum,

I first began researching John’s history when my Project Manager at The Brickworks Museum lent over my desk to point at an image I was looking at. ‘That’s our Black brickworker,’ she said highlighting one of the men in a photograph of brickworkers outside of our kilns. With his steely gaze, lighter suit and darker skin John Honton is recognisable as being a minority in early Edwardian England. Here we piece together his life up to the 1920s from newspaper clippings, birth, death and marriage certificates, the census and from speaking to John’s relatives.

John was born in Isandlwana, South Africa in 1869, son of Johannes who is described on documentation as a ‘Foreman of Coolies’. The latter is a now outdated slur for Chinese tea workers. We don’t know what brought John to England, but by 1902 he had reached our shores and was working as an elephant trainer for Sanger’s Circus, seemingly adopting the name Zulu James. Newspaper reports fill in part of his story – in 1902 a huge bull elephant by the name of Mammy, trained to trumpet the patriotic song “Rule, Britannia!” and stand on his head – seized John, threw him to the floor and proceeded to gore him severing two fingers at the tip. Another member of staff leapt to save John, suffering his own injuries in the process. John, despite bleeding heavily from his hand, distracted the elephant and dragged his colleague to safety. The elephant was shot at midnight and John was devastated.

This might explain why, by 1906, he had left the circus, found employment at the Bursledon Brick Company and settled in Hampshire to marry local girl May Fielder. In 1906 John also felt the long arm of the law for the unforgivable crimes of cycling without lights and failing to ring his bell when passing another road user, a crime which Constable Davis was able to prove and for which John was fined the mighty sum of five shillings, equivalent to around £20 today.

John’s marriage to May lasted just eight months before she succumbed to pneumonia. She is buried in the local churchyard.

In 1914 war broke out and in September Messrs C and H Ashby, the owners of the works, heartily encouraged their employees to enlist in support of King and Country, it being ‘the duty of every eligible man.’ John volunteered however his offer was rejected. In the context of years of colonial rule, it was deemed unpalatable by the British Government that Black men should be trained, armed and encouraged to shoot at white men, even if the white men concerned were Axis forces. “Native” Labour Corps were established, aiming to make use of Black men in supplying and facilitating Kitchener’s army, releasing more men of British descent to fight. John was not offered the option of enlisting in a labour corps and despite his willingness and apparent keenness to support his adoptive country, his offer was rejected. He stayed at the Brickworks.

The war ended and some of the men returned having had their jobs guaranteed by factory founders the Ashby’s; the women who had been drafted to the works to fill munitions were thanked for their service and sent back home; and the 1920s dawned.

John was dedicated to his work at The Brickworks and served the factory throughout the whole of the 1920s – he received his long service medal for completing over 25 years of service in 1931, having worked for the company since 1904. Life at the Brickworks was hard – the engine workers started at 6am, the clay diggers shortly after and the brickmakers were all in place by 8am. We don’t know what job John undertook for the Brick Company but it is likely that he came in at the lowest level of sandboy or barrow boy, and worked his way up to kiln worker. In the winter the clay would freeze and in the summer the physical work in heated drying rooms or unloading the kilns was punishing – very little stopped the machines though and the output of bricks, some 20 million a year, was constant.

It wasn’t all work and no play for the men of the works. As well as football matches and the ever popular tug of war (for which we hold the trophies in the museum) the workers were treated to annual outings courtesy of the management. This is where we see John again, leaning back onto a friend, smartly dressed and eschewing a hat in a group photograph taken in 1922 during a groups outing. In evidence in the photograph are not one but two squeezeboxes – an instrument that John apparently played though it appears not on this outing – and a violin, hinting at the day’s entertainment.

Photographer of the brickworkers of Burlesdon Brick Company on a summer outing, featuring John seated five from left, second row. Source: the archives of the Brickworks museum

He appears in one more photograph taken on a different summer’s day and a different work’s outing, also likely during the 1920s. This photograph was posed with three horse drawn charabancs, one of which John sits confidently on the roof of accompanied by friends and colleagues.

Whilst John had left the circus after the death of Mammy in 1902, he never forgot his training. In the 1920s Sangers circus travelled through Swanwick and John visited the big top. The elephants in the show were performing when one failed to follow his handler’s command. A tense hush fell over the audience as this massive beast refused to do as he was bid, his handler becoming increasingly frustrated. From the audience, John stood up and bellowed the correct command. The elephant obeyed and John returned to his seat.

The Brickworks Museum in Southampton is the only steam driven brickworks in the UK and is a rare survivor of industrial history. You can walk in the footsteps of brickmakers and learn about the history of the old factory. It still has all it’s working machinery and is steamed up once a month as a working exhibit. Find out more at thebrickworksmuseum.org