Download documents and transcripts

Teachers' notes

The purpose of this document collection is to allow students and teachers to develop their own lines of historical enquiry or historical questions using original documents on this period of history. Students could work with a group of sources or particular document series which identifies a certain theme. Of course the sources offer students a chance to develop their powers of evaluation and analysis and support their course work. Teachers may wish to use the collection to develop their own resources or encourage students to ‘curate’ their own ‘exhibition’ of the most significant documents on the topic. Finally, there is an opportunity to consider film sources as interpretations of these events in relation to the documents by following the link to Pathé provided here.

The introduction helps you to understand the causes for Indian partition, how it happened, how was it experienced by ordinary people, and how we can know more about it through primary sources and oral history sources. Some suggestions for further reading are also provided.

Please note that the introduction and some of the source collection contains references to physical and sexual violence, please avoid reading if necessary.

Selected Readings:

Butalia, Urvashi. The Other Side of Silence Voices from the Partition of India. New Delhi: Penguin Books, 2014.

Jalal, Ayesha. The Sole Spokesman: Jinnah, the Muslim League and the Demand for Pakistan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Khan, Yasmin. The Great Partition: The Making of India and Pakistan. New Haven, CT: Yale University, 2017.

Zamindar, Vazira Fazila-Yacoobali. The Long Partition and the Making of Modern South Asia: Refugees, Boundaries, Histories. Columbia University Press, 2007.

Connections to the curriculum

These documents can be used to support any of the exam board specifications covering the history of Indian Independence in 20th century for example:

Edexcel: GCSE History A

Unit 4: Representation of history: CA7: The Indian subcontinent: The road to

Independence 1918-47. In this unit students are required to carry out their historical enquiry and also make links between modern representations of this period of history.

Edexcel: GCE

Unit 2: British Depth Studies: Option D2 for AS

Britain and the Nationalist Challenge in India, 1900-47 content including:

The impact of the Second World War on the relationship between Britain and India economic and political imperatives in Britain and India driving independence; role of Mountbatten; the decision to partition and the immediate consequences of that decision.

Edexcel GCE

Unit 4: Historical Enquiry for A2

CW21: Britain and India, 1845-1947

The documents in this collection can be used to support this enquiry led unit:

OCR GCSE History B

End of Empire Key Question 3: How well did Britain deal with the issue of Indian independence?

The documents in this collection can be used to support this unit.

Introduction

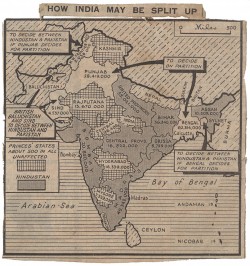

Before the British colonial officials left India in 1947, the subcontinent was divided into two different nations: India and Pakistan. India came to be ruled by the nationalist Congress Party under Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru’s prime ministership, and Pakistan by the Muslim League under the leadership of Muhammad Ali Jinnah.

The emergence of two nations was premised on religious divide—Pakistan for Muslims and India for Hindus, though India chose to become a secular republic. About 35 million Muslims remained in secular India. The origins of partition stretch back to the politics of nationalist leaders and the colonial state since the 1940s onwards.

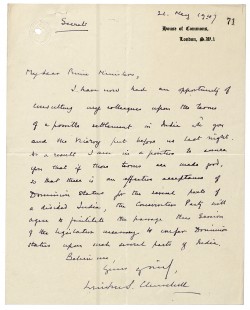

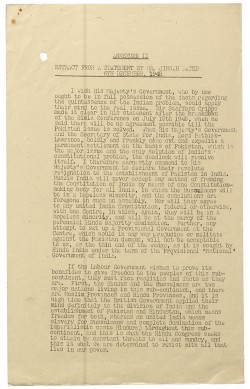

To secure Indian cooperation in the Second World War, the Churchill government agreed to send the Cripps Mission in 1942 to resolve the Indian political situation. Though failed to satisfy nationalist leaders, the Mission proposed the idea of independence for India after the War. [See the documents on Cripps Mission].

As the tide of anti-colonial nationalism began to shape the demand for an independent nation, the Muslim League Party under Jinnah began to mobilise the different classes of Muslims to demand Muslim’s right for self-determination. The demand for Pakistan as a separate territorial nation remained fluid and limited in the early 1940s, but during the provincial elections, the League mobilised Muslims, especially the lower and middle classes, in the name of Pakistan. The huge electorate mandate of the League in Muslim regions increased and popularised the demand for a separate nation for Muslims. [See the record, Jinnah on Partition].

The British not only helped to consolidate the Muslim League in the East and the West by installing League ministries in 1942-43, but they also aired the idea that regions could secede from the Union through the Cripps Mission, legitimising Jinnah’s call.

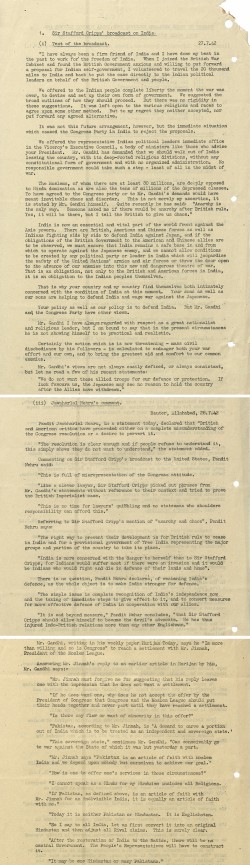

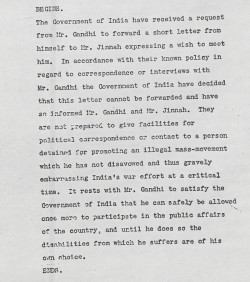

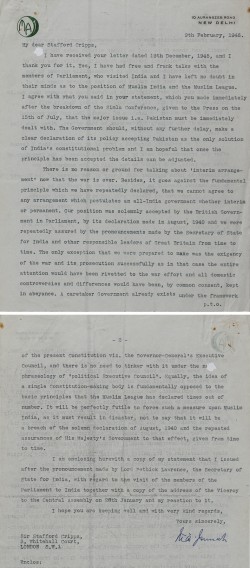

The Congress Party under M.K. Gandhi, Nehru, and other leaders demanded a free united India. [See, the Letter by UK High Commissioner Terence Shown dating 14th October, 1947]. It was not acceptable to Jinnah who in his 1945 speech said, “Whereas a united India means slavery for Mussulmans and complete domination of the imperialistic caste Hinduraj throughout this sub-continent.” [See the source titled, Jinnah’s Call for Pakistan].

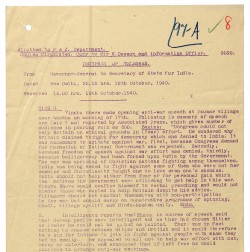

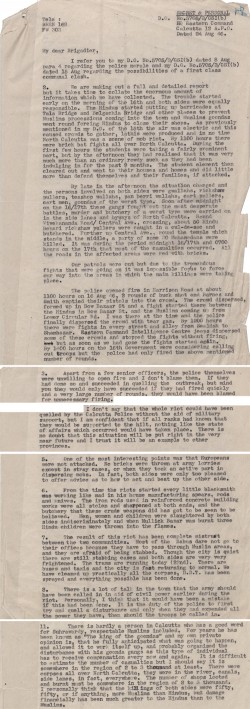

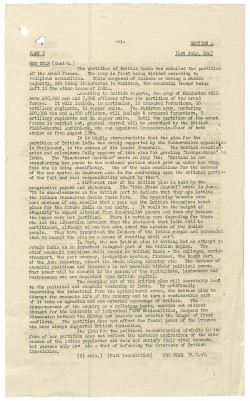

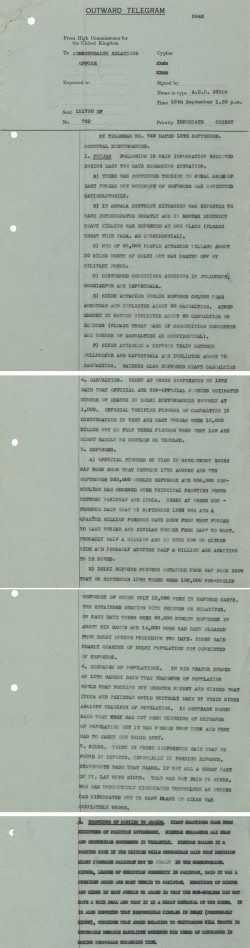

The Quit India Movement of Gandhi, the cost of the Second World War, and the Indian Naval Mutiny in 1946 made Britain realise that India could no longer be ruled. Hence, the newly formed Labour Party British government under Clement Attlee in July 1945, which was sympathetic to India’s self-determination but determined to safeguard British economic interest and influence in South Asia, sent a Cabinet Mission in 1946 to discuss the formation of independent India. The Mission failed and the League called for a popular agitation for Pakistan demand which led to killings of Hindus by Muslims in Calcutta accompanied by a reactionary violence by Hindus in Calcutta and other parts of India. [Read the British Military Report on the Great Calcutta Killings].

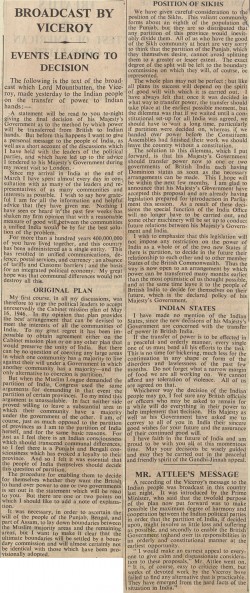

The British decided to leave by June 1948, but the Viceroy Louis Mountbatten moved this forward to August 1947. The press in the USA praised Attlee’s decision of actual withdrawal as otherwise, the New York Herald Tribune noted, “The British might easily have lingered on in India, playing off Hindu against Moslem, prince against peasant, presiding over a tense and costly stalemate in the interests of imperial prestige.”

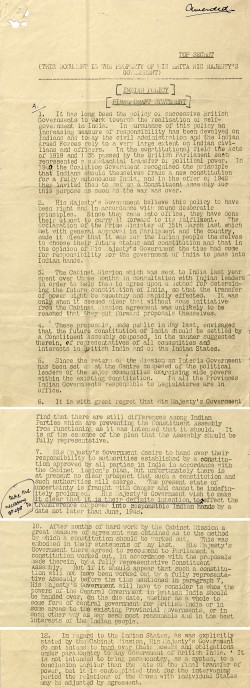

Sir Cyril Radcliffe was asked to draw border lines of the two nations within six weeks. As Muslims concentrated on both the East and the West side of British India, Pakistan was split into two awkward regions: the West-side Pakistan and the East Pakistan (which became Bangladesh in 1971). Jinnah was unhappy with a truncated Bengal and Punjab, though his goal of a sovereign nation for Muslim was achieved. [Figure out his discontent from his 1947 statement]. What followed the creation of Pakistan on 14th August 1947 was a large migration of Hindus and Sikhs from Pakistan to India and of Muslims to Pakistan resulting in one of deadliest communal violence between the two communities amidst building tensions on religious lines, lack of law and order at the time of quick power transfer, uncertain migration.

About one million people died, more than seventy-five thousand women were raped, and 10 million people were displaced along with a huge destruction of property. The horrors of partition violence left a never-ending legacy onto the families and psyche of migrants who lost their homes, family members, experienced significant years of life in harsh displacement (migrant camps and refugee colonies) and witnessed violence first hand.

Although historians’ focus has moved away from determining the causes of the partition and the role of elites to the meanings of partition and its violence on the two communities, this document collection of official papers covers key moments leading to the partition between 1939-47: the Second World War, the ideas of Indian nationalist leaders and their differences such as of Jinnah, Gandhi, Bose, the British officials’ thought on the transfer of power, the partition violence, and the fate of Pakistan. Along with these, you could also listen to the voices of partition-affected people from these oral histories, collected by TNA, which have emerged as a key source for historians to integrate memory as a source of history writing with official documents.

Dr Arun Kumar

Assistant Professor in British Imperial, Colonial & Post-Colonial History

University of Nottingham

https://twitter.com/arun_historian

Dr. Heena

The Newton International Fellow

Edinburgh University

External links

- 1947 Partition Archive

The 1947 Partition Archive records life stories shaped by Partition - Bangla Stories

Accounts of emigrants from Bengal after independence. The website also includes resources for students and teachers - British Pathé

Pathé hold a large amount of footage relating to India and independence which can be watched online - Flashback to Indian partition

Listen to archive recordings of Jinnah, Nehru and Mountbatten from the BBC - Manas: History and Politics of India

Useful UCLA site with a number of bibliographies - Child of Empire

Project Dastaan have created this VR experience to mark the 75th anniversary of the Partition of India - National Army Museum: Independence and Partition, 1947

This website from the National Army Museum contains information on the impact of Partition and a video called ‘Reflections and Recollections’