Andrés Manuel de Villarreal: a bourbon ‘multi-archivist’ in the Colonial Santiago of Chile

By Claudio Ogass Bilbao

Andrés Manuel Villarreal performed multiple recordkeeping and archival duties in five different institutions both as secretary and as archivist in Santiago of Chile – the capital of the remotest colony of the Spanish monarchy – between the end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century. During that period, he created the first written official register of public and royal notaries in the city and asked the political authorities for the establishment of a College of Notaries to encourage better, standardized practices among the local public servants. Furthermore, he persecuted and dismantled a smuggling network that had been stealing and selling public records with complete impunity, a great portion of them under his custody. Finally, he formed several indexes and inventories that contributed enormously to the development and dissemination of organization and description knowledge and practices among his colleagues.

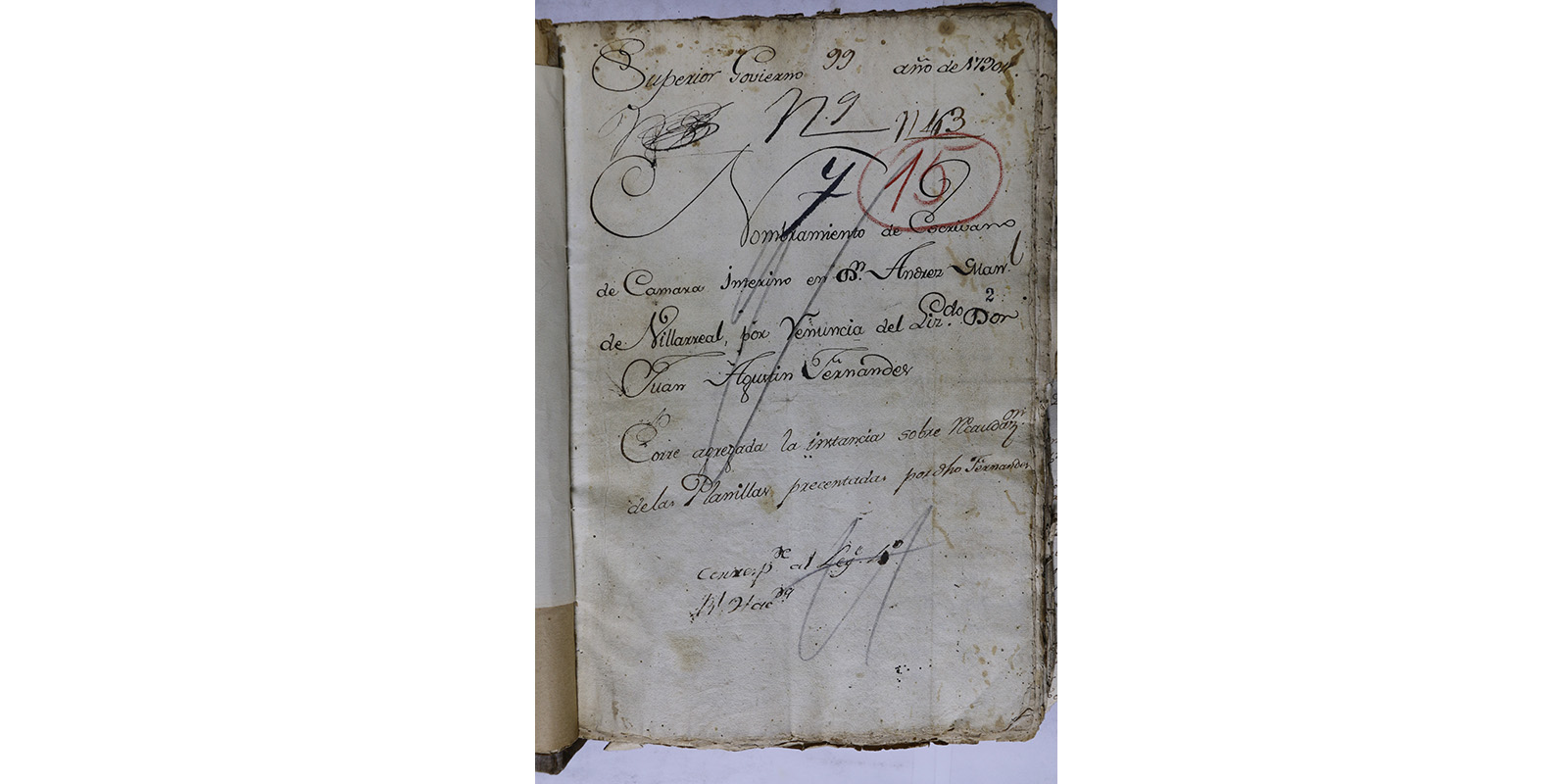

Moreover, Villarreal’s main contribution to Chile’s archival history – and, maybe, to the Latin-American one as well – was that he followed the ‘principle of provenance’ while he managed diverse documentary institutional evidence. Between 1788 and 1809, he administered the First Notary and the Cabildo offices, while he performed as interim secretary on the Secretariat of Chamber on the Royal Audience. Additionally, he was the notary on the Direction of Tobacco and the Mining Notary, but the exact dates are unknown. In this regard, he could be considered as a ‘multiarchivist’ as he served simultaneously on at least three different Archives, according to his testimonies.

In all those political, judicial, and economic institutions, he oversaw the writing, the organization, the description, and the appraisal of official documents, taking care of not mixing them, advice he strongly recommended be taken by his assistants. In his own words: ‘I never transferred a piece of paper from the Secretariat of the Chamber to the council office (Cabildo) of my position (…) I have had them [the different records] separated from each other in different drawers, with their respective inventories and letterheads (brevetes), and with due arrangement regarding those offices’. This case strongly demonstrates that this principle of provenance is more practical than theoretical, and its empirical use can be traced long before the ideas by Natalis de Wailly (1841) and the Dutch Manual (1898) were formulated and became widespread.

In 1791, the judge Juan Rodríguez Ballesteros asked the Cabildo notary to make a list of the public notaries who had held the position in the last 30 years. To make this certificate, Villarreal reviewed the books kept in the Archive of the institution, realizing the difficulty of establishing the exact dates of duration of his predecessors, since his colleagues usually did not enroll their titles in the organization. On 29 October of that year, he requested the creation of a College of Notaries, becoming one of the first promoters of union and labour cooperation in the city. Following some institutional models and examples from Spain and Mexico, his idea was to standardize official practices to improve public service in the Kingdom by holding regular meetings to share experiences and problems and clarify daily doubts. However, this initiative was ignored by the authorities.

Eleven years later, on 14 May 1800, Villarreal dismantled a notarial document smuggling network made up of 13 buyers and seven sellers. According to his testimony, Pedro de Villanueva, one of his officers at the Santiago notary, used his keys to open his office at night and sell his old records mainly to chocolatiers wanting to use the paper to wrap their products, trying to profit considering the general context of scarcity and rising prices of paper. For this reason, Villarreal went to houses, stores, offices, and chocolate shops to retrieve the stolen records. In total, he recovered 55 files, 86 notebooks, two reams and innumerable old protocol papers belonging to scribes between 1597 and 1679. Although he tried to have those involved punished for betraying public faith, only a few were imprisoned.

In this sense, his encouragement of greater unionization, his archival awareness expressed in the strong defense of the value of documents and archives as guarantors of public faith and, the order of his offices (avoiding the mixing of papers of different origins) transformed Andrés Manuel Villarreal into a valuable character in Chilean, Latin American and global archival history. The work history and fragments of Andrés Manuel Villarreal’s archival thought are known mainly from the requests he presented at the Royal Audience of Santiago. Unfortunately, its history is incomplete due to the further neglect and lack of awareness of colonial archives in the country.

Image credit: Nombramiento de Escribano de Cámara interino de don Andrés Manuel Villarreal, 1790, ID: Fondo Real Audiencia, volumen 3168, f. 1, Archivo Nacional (Chile)