As a style of drawing, caricature, or the exaggeration of a person’s physical features for comic effect, has been used more frequently to make a political point, leading to the development of the sort of cartoons we are now familiar with. Caricature was first was used in Italy early in the seventeenth century. It was introduced into England in the eighteenth century by those returning from the Grand Tour, an extended cultural trip around Europe for wealthy young men to finish their education.

The Eighteenth Century

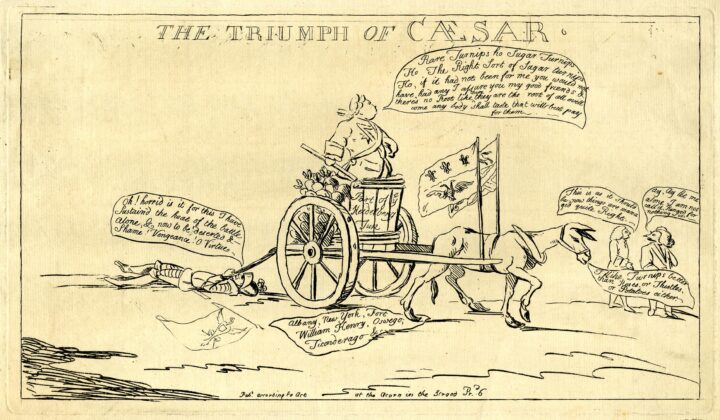

George Townshend, later Marquis Townshend (1724-1807), was among the first to use caricature as a means of political satire in the 1760s. He produced comic portraits which were used in the London Magazine, the Political Register, and the Town and Country Magazine. Here is one of his cartoons from 1757 entitled ‘The Triumph of Caesar’.

The cartoon shows the Duke of Cumberland, Prince William driving a farm cart containing turnips. The cartoon is critical of William’s focus on the alliance with Prussia during the Seven Year’s War in Europe at the neglect of British colonial interests in North America (shown listed on a paper on the ground.) There are also politicians in the cartoon: Henry Fox, (Lord Holland) and Thomas Pelham-Holles, (Duke of Newcastle) with the King of Prussia, Frederick the Great, nephew of George II, shown as a soldier lying down next to a Prussian flag). The royal house of Hanover was German in origin and symbolised in the cartoon by the reference to turnips grown in Hanover.

From the eighteenth century, the political cartoon became a recognised form of social and political commentary, taking serious issues or figures of the day and presenting them accessible way designed to affect the viewer’s opinion.

In Britain, James Gillray (1757-1815) and Thomas Rowlandson (1756-1827) made fun of political figures and issues. Unlike today’s cartoonists, Gillray was unable to publish his work in the newspapers. He displayed it in his publisher’s shop window in New Bond Street, London. Customers could buy a copy for a few shillings or even rent the pictures for a dinner-party to amuse their friends.

‘The plumb-pudding in danger’ is one of Gillray’s most famous cartoons. It shows British Prime Minister William Pitt and Napoleon Bonaparte dining together. Pitt wears a regimental uniform and hat and both men use huge swords to carve up a large plum pudding in the appearance of the globe. The men help themselves, one taking the land, the other the sea, as if by right. They are both very thin, hence their ‘insatiable’ appetites, according to the caption. Clearly, they need to be fed. This explains why the world or ‘the plumb pudding’ is ‘in danger’. Napoleon Bonaparte and William Pitt are both intent on their task. Pitt appears calm, careful, and controlled, spearing the pudding with a trident fork, a symbol of Britain’s superior navy. He claims the oceans and the West Indies. His ‘slice’ is much larger than Napoleon’s. Pitt is shown as the more powerful figure with Napoleon, his inferior, trying to get what he can. Bonaparte is drawn smaller; his hat too large and standing at the table rather than sitting. His greedy eyes are fixed on the prize of Europe as he cuts his slice of the ‘pudding’.

Wikipedia Commons Public domain. Transcript: ‘The plumb-pudding in danger: – or – State epicures [a person dedicated to good food and drink] taking un [a] Petit Souper [small dinner]. The great globe itself and all which it inherit is too small to satisfy such insatiable appetites”

The cow-pock – or – the wonderful effects of the new inoculation / Js. Gillray, del. & ft. Abstract/medium: 1 print : engraving, color., 1802. Gillray, James, 1756-1815, artist. Courtesy of U.S. Library of Congress

The cartoon reflects the controversy over inoculation against smallpox and was rumored to cause cow-like growths on the body. A boy holds a container of the vaccine (taken from cowpox blisters as it gave immunity to smallpox) and in his pocket is a paper on the ‘Benefits of the Vaccine’. Cowpox was a mild infection often caught by those who worked with cows. We can also see a tub on the desk called ‘Opening mixture’. A bottle next to the tub is labeled ‘vomit’. These suggest there may be other side effects to the vaccine. Finally, a painting on the wall shows ‘Worshippers of the Golden Calf’, to reflect supporters of vaccination.

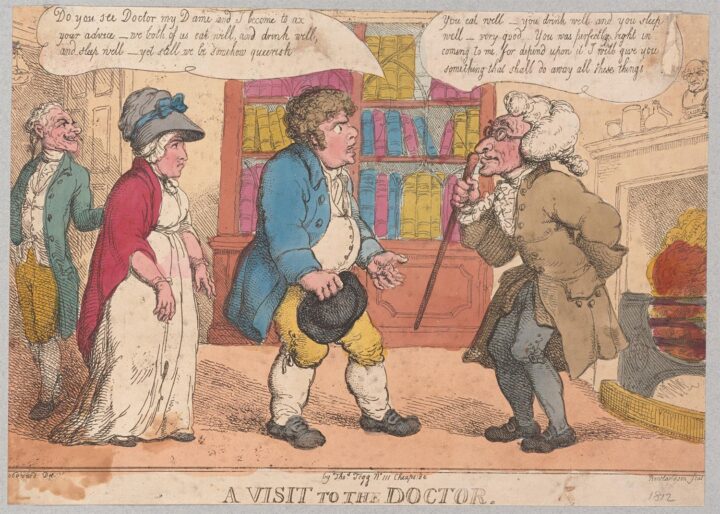

Another caricaturist, Thomas Rowlandson (1756-1827), did not hold back when making fun of political figures and issues either. Rowlandson created many images of life in Georgian London as a social and political observer. In this cartoon ‘A visit to the doctor’ he satirized the medical profession.

In the cartoon there is a bust of Gallen on the mantelpiece. This is important as Claudius Gallen c.130 AD-c.210 AD was one of the most important doctors within the Roman Empire who developed the idea of the experimental method in medical investigation. The cartoon criticised the medical profession for unnecessary expensive treatments. It suggests that treatments can also cause harm to the health of the patient. His work included the creation of a character called John Bull to represent the British common man from about 1790, a character developed by James Gillray and George Cruikshank.

‘A visit to the doctor’, circa 1809 (Courtesy of the Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University). Man: Do you see Doctor my Dame and I come to [ask] your advice- we both of us eat well and drink well and sleep well- yet still we be somehow queerish [unwell]. Doctor: You eat well- you drink well and you sleep well- very good. You are perfectly right in coming to me, for depend upon it I will give you something that shall do away all these things.

The example concerns the marriage of George Prince Regent and his wife Caroline of Brunswick. George was about to be crowned king, on the death of his father. He wanted a divorce and, exclude Caroline from the coronation. The ‘Pain and Penalties Bill was introduced into Parliament to deprive her of her position and grant the divorce. In the 1830s Cruikshank also produced book illustrations, notably for Charles Dickens’s Sketches by Boz (1836) and Oliver Twist (1838). In later life he embraced the cause of temperance (for moderation or abstinence in drinking) with his series The Bottle (1847) and The Drunkard’s Children (1848).

The later nineteenth century

In Britain, the weekly humour and satirical magazine Punch started in 1841 and featured the work of men like John Leech (1817-1864) whose drawings were the first to be called cartoons. Prints ceased to be published as single sheets and became part of newspaper and periodical illustration.

John Tenniel (1820-1914) was another cartoonist to emerge. He was who was very influential, especially for his use of symbols such as Britannia, John Bull, Uncle Sam, the British Lion, and the Russian Bear. At the start of the twentieth century, the production of daily newspapers grew, and the political cartoon became a regular and established feature of journalism.

Twentieth Century

The two world wars and the subsequent peace treaties provided fertile ground for cartoonists such as Low, Dyson, Strube, Vicky and Illingworth. David Low’s work was highly influential, with his creation of ‘types’ which were reminiscent of Gillray and Cruikshank’s ‘John Bull.’

During wartime, the political cartoon was a powerful weapon, used to boost morale and use as propaganda. In Britain, the Ministry of Information made extensive use of them.

The use of cartoons continued to grow after the Second World war. The Times adopted a daily cartoon in 1966. In any newspaper today and you can see the latest offering from this profession. The work of Ronald Searle (1920–2011), Gerald Scarfe (1936–), and Ralph Steadman (1936–) captured some of the brutality of Gillray and Rowlandson. This continues with an anti-establishment position which can be seen in the cartoons of ‘Private Eye’ magazine (founded in 1961).

In the age of television, Peter Fluck and Roger Law, produced three-dimensional caricatures of a savagery reminiscent of Gillray for the ITV series ‘Spitting Image’ (1984–96).

Sources for cartoons

Use the links below to find the work of various cartoonists and satirists. Practice your skills with these types of images.

- Find more 20th century cartoons in the data base for the British Cartoon Archive at University of Kent.

- Why was the work of William Hogarth significant?

- Explore more works by George Cruikshank.

- Learn about the life and work of caricaturist and artist, James Gillray .

- Explore a large collection of 18th British satire and caricature.

- Search Punch Archive for 19th century political cartoons.