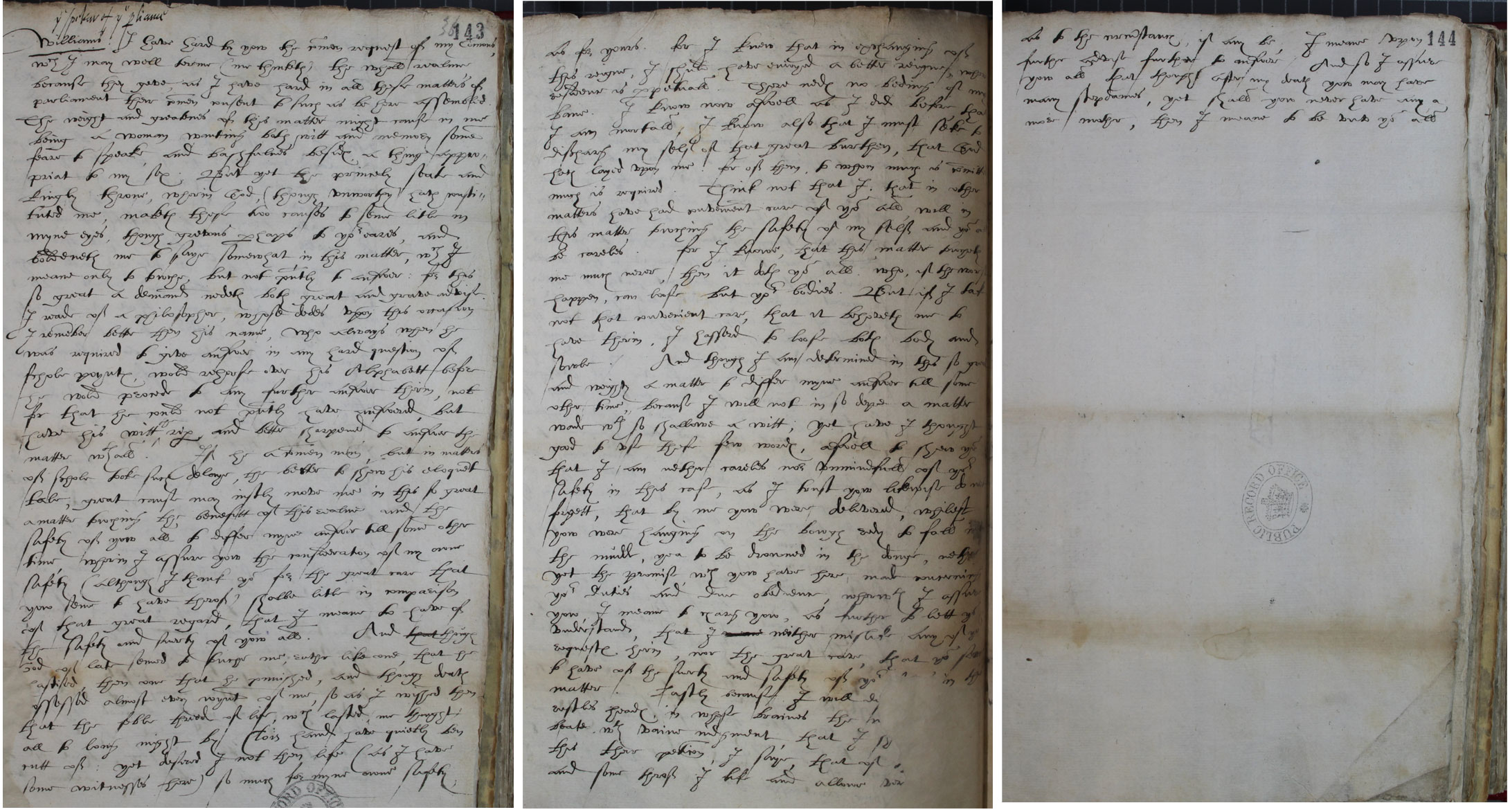

Answer of the Queen to the addresses of both Houses of Parliament delivered to Mr Speaker Thomas Williams, 28 January 1563 (SP 12/27 f.143r-144v)

From the very beginning of her reign, Elizabeth was determined never to marry. In an age when women were considered naturally subservient to, and in need of guidance from men, this was deeply shocking to her advisers and subjects. Moreover, the kingdom needed an heir so it was imperative that the queen take a husband. But having battled so hard for the throne, Elizabeth was not minded to cede any of her authority to a husband. Fully appreciating the diplomatic importance of keeping her various suitors in play, however, she proved a master of procrastination and giving ‘answers answerless’.The matter became more pressing after the queen’s near-fatal attack of smallpox in October 1562, so Parliament again petitioned her to marry. Elizabeth cleverly used her gender to side-step the issue, claiming that she could not respond as a woman ‘wanting wit and memory’, and that she was too bashful to speak of marriage.

Transcript

Williams: I have hard [heard] by yow the common request of my Commons, which I may well terme (me thinketh) the whole realme because they geve, and I have hard [heard] in all these matters of parliament their common consent to such as be hear assembled. The weight and greatnes of this matter might cause in me being a woman wanting both witt and memory some feare to speake and bashfulnes besides, a thing appropriat to my sex. But yet the princely seate and Kingly throne, wherein God (though unworthy) hath constituted me, maketh these two causes to seme litle in myne eyes, though grevous perhaps to your eares, and boldeneth me to saye somewhat in this matter, which I meane only to touche but not presently to answer: for this so great a demand needeth both great and grave advise. I read of a philosopher, whose dedes upon this occasion I remember better then his name, who always when he was required to give answer in any hard question, of schole [school] poyntes, wold rehearse over his Alphabett before he wold procede to any further answer therin, not for that he could not presently have answerd, but have his witt the riper and better sharpened to answer the matter withal. If he a common man, but in matters of schole [school] tooke suche delaye, the better to show his eloquent tale, great cause may justly move me in this so great a matter touching the benefit of this realme and the safety of you all, to differ [defer] myne answer till some other time, wherin I assure you the consideration of my owne safety (although I thank you for the great care that you seme to have therof) shalbe litle in comparison of that great regard, that I meane to have of the safety and surety of yow all. And thoughe God of late semed to touché me, rather like one, that he chastised, then that he punished, and thoughe death possessed almost every joint of me, so as I wyshed then that the feble thread of life, which lasted, me thought, all to longe, might by Clotho’s hand have quietly ben cut off: yet desired I not then life (as I have some witnesses hear) so much for myne owne safety as for yours. For I know that in exchanging of this reigne, I shuld have enjoyed a better reigne, where residence is perpetuall. There nedes no boding of my bane. I know now aswell as I did before that I am mortall. I know also that I must seke to discharge my self of that great burthen, that God hath layed upon me. For of them, to whom much is committed, much is required. Think not that I that in other matters have had convenient care of you all, will in this matter touching the safety of my self and you all be careless. For I know, that this matter toucheth me much nearer, then it doth you all. Who, if the worst happen, can loose but your bodies. But if I take not that convenient care, that it behoveth me to have therin, I hazzard to loose both body and soule. And though I am determined in this so great and weighty a matter to differ [defer] myne answer till some other time, because I will not in so depe a matter wade with so shallowe a witt; yet have I thought good to use these few wordes, aswell to shew you that I am nether careles nor unmindfull of your safety in this case, as I trust yow likewise do not forgett, that by me you were delivered, whilest you were hanging on the bowgh [bough] redy to fall into the mudd, yea to be drowned in the dogne [dung], nether yet the promise, which you have here made concerning your dutis and due obedience, wherewith I assure you, I meane to charge you, as further to let you understand, that I neither mislike any of your requestes herin, nor the great care, that you seme to have of the surety and safety of yourselves in this matter. Lastly because I will discharge some restles heads, in whose braines the needless hammers beate with vaine judgement, that I should mislike this their petition, I saye, that of the matter and some thereof I like and allowe very well. As to the circumstances, if any be, I meane upon further advyse further to answer, And as I assure you all that though after my death yow may have many stepdames, yet shall yow never have any a more mother, then I meane to be unto you all.