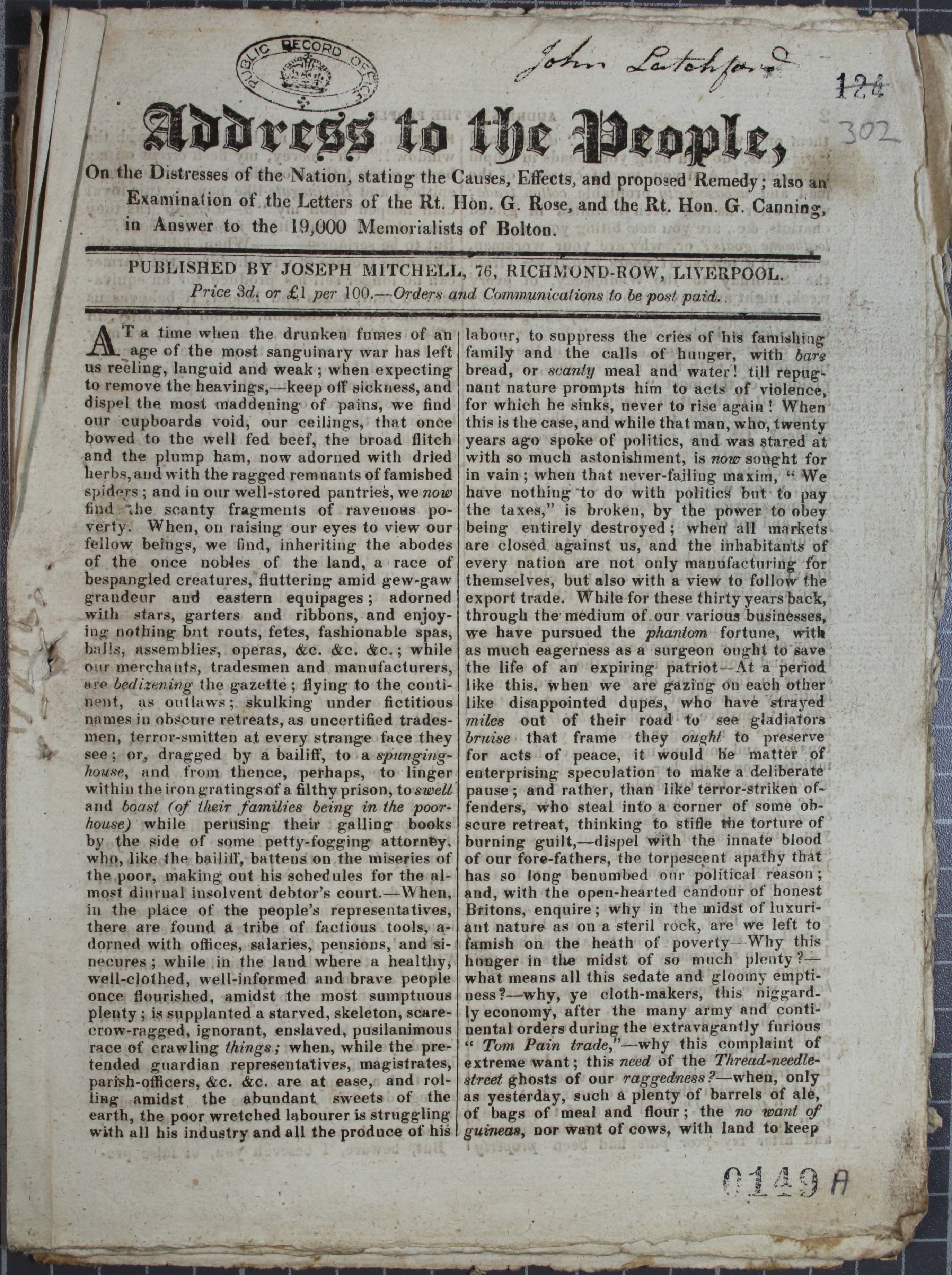

This is the first page of a pamphlet from a collection of printed material found on radical prisoners – in this case John Latchford, 1815-1817. It is called an ‘Address to the People’ by the Lancashire radical Joseph Mitchell. It is important for its political analysis of causes of poverty (war, tax, corruption). It predates William Cobbett’s more famous ‘Address to Journeymen and Labourers’ by a month and is from the north of England, c early October 1816. (HO 40/9 f302)

Transcript

On the Distresses of the Nation, stating the Causes, Effects, and proposed Remedy; also an Examination of the Letters of the Rt. Hon. G. Rose, and the Rt. Hon. G. Canning, in Answer to the 19,000 Memorialists of Bolton.

PUBLISHED BY JOSEPH MITCHELL, 76, RICHMOND-ROW, LIVERPOOL.

Price 3d. or £1 per 100. Orders and communications to be post paid.

At a time when the drunken fumes of an age of the most sanguinary war has left us reeling, languid and weak; when expecting to remove the heavings, — keep off sickness, and dispel the most maddening of pains, we find our cupboards void, our ceilings, that once bowed to the well fed beef, the broad flitch and the plump ham, now adorned with dried herbs, and with the ragged remnants of famished spiders; and in our well-stored pantries, we now find the scanty fragments of ravenous poverty. When, on raising our eyes to view our fellow beings, we find, inheriting the abodes of the once nobles of the land, a race of bespangled creatures, fluttering amid gew-gaw grandeur and eastern equipages; adorned with stars, garters and ribbons, and enjoying nothing but routs, fetes, fashionable spas, balls, assemblies, operas, &c. &c. &c.; while our merchants, tradesmen and manufacturers, are bedizening the gazette; flying to the continent, as outlaws; skulking under fictitious names in obscure retreats, as uncertified tradesmen, terror-smitten at every strange face they see; or, dragged by a bailiff, to a spunging-house, and from thence, perhaps, to linger within the iron gratings of a filthy prison, to swell and boast (of their families being in the poor-house) while perusing their galling books by the side of some petty-fogging attorney, who, like the bailiff, battens on the miseries of the poor, making out his schedules for the almost diurnal insolvent debtor’s court. — When, in the place of the people’s representatives, there are found a tribe of factious tools, adorned with offices, salaries, pensions, and sinecures; while in the land where a healthy, well-clothed, well-informed and brave people once flourished, amidst the most sumptuous plenty; is supplanted a starved, skeleton, scarecrow-ragged, ignorant, enslaved, pusilanimous race of crawling things; when, while the pretended guardian representatives, magistrates, parish-officers, &c. &c. are at ease, and rolling amidst the abundant sweets of the earth, the poor wretched labourer is struggling with all his industry and all the produce of his labour, to suppress the cries of his famishing family and the calls of hunger, with bare bread, or scanty meal and water! till repugnant nature prompts him to acts of violence for which he sinks, never to rise again! When this is the case, and while that man, who, twenty years ago spoke of politics, and was stared at with so much astonishment, is now sought for in vain; when that never-failing maxim, “We have nothing to do with politics but to pay the taxes,” is broken, by the power to obey being entirely destroyed; when all markets are closed against us, and the inhabitants of every nation are not only manufacturing for themselves, but also with a view to follow the export trade. While for these thirty years back, through the medium of our various businesses, we have pursued the phantom fortune, with as much eagerness as a surgeon ought to save the life of an expiring patriot —At a period like this when we are gazing on each other like disappointed dupes, who have strayed miles out of their road to see gladiators bruise that frame they ought to preserve for acts of peace, it would be matter of enterprising speculation to make a deliberate pause; and rather, than like terror-stricken offenders, who steal into a corner of some obscure retreat, thinking to stifle the torture of burning guilt, —dispel with the innate blood of our fore-fathers, the torpescent apathy that has so long benumbed our political reason; and, with the open-hearted candour of honest Britons, enquire; why in the midst of luxuriant nature as on a steril rock, are we left to famish on the heath of poverty —Why this hunger in the midst of so much plenty? —what means all this sedate and gloomy emptiness? —why, ye cloth-makers, this niggardly economy, after the many army and continental orders during the extravagantly furious “Tom Pain trade,” —why this complaint of extreme want; this need of the Thread-needle-street ghosts of our raggedness? —when, only as yesterday, such a plenty of barrels of ale, of bags of meal and flour; the no want of guineas, nor want of cows, with land to keep them on;