Memo sent by the Secretary of State to the Home Office, Secretary of State for Scotland and Minister for Education, 25th November 1954 (PREM 11/858)

Transcript

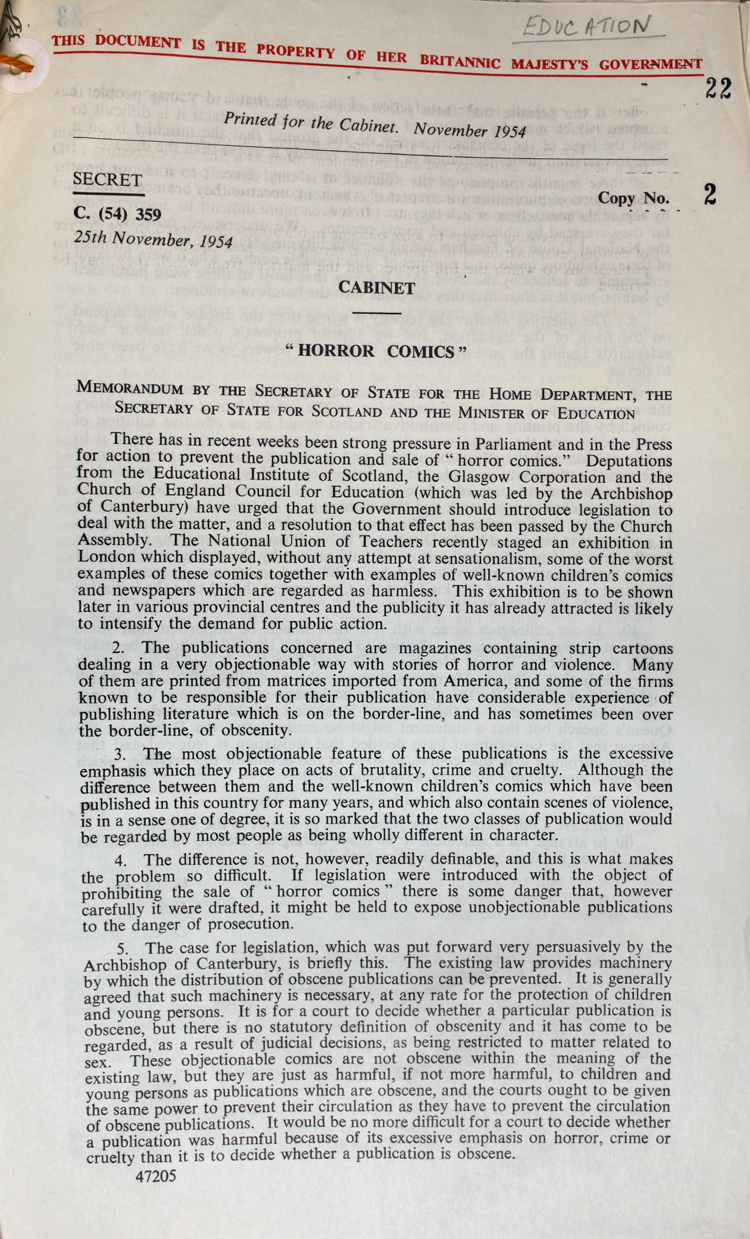

SECRET

C. (54) 359

25th November, 1954

“HORROR COMICS”

MEMORANDUM BY THE SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE HOME DEPARTMENT, THE SECRETARY OF STATE FOR SCOTLAND AND THE MINISTER OF EDUCATION

There has in recent weeks been strong pressure in Parliament in the Press for action to prevent the publication and sale of “horror comics”. Deputations from the Education Institute of Scotland, the Glasgow Corporation and the Church of England Council for Education (which was led by the Archbishop of Canterbury) have urged that the Government should introduce legislation to deal with the matter, and a resolution to that effect has been passed by the Church Assembly. The National Union of Teachers recently staged an exhibition in London which displayed, without any attempt at sensationalism, some of the worst examples of these comics together with examples of well-known children’s comics and newspapers which are regarded as harmless. This exhibition is to be shown later in various provincial centres and the publicity it has already attracted is likely to intensify the demand for public action.

2. The publications concerned are magazines containing strip cartoons dealing in a very objectionable way with stories of horror and violence. Many of them are printed down from matrices imported from America and some of the firms known to be responsible for their publication have considerable experience of publishing literature which is on the border-line, and has sometimes been over the border-line, of obscenity.

3. The most objectionable feature of these publications is the excessive emphasis which they place on acts of brutality, crime and cruelty. Although the difference between them and the well-known children’s comics which have been published in this country for many years, and which also contain scenes of violence, is in a sense one of degree, it is so marked that the two classes of publication would be regarded by most people as being wholly different in character.

4. The difference is not, however, readily definable, and this is what makes the problem so difficult. If legislation were introduced, with the object of prohibiting the sale of “horror comics” there is some danger that, however carefully it was drafted, it might be held to expose unobjectionable publications to the danger of prosecution.

5. The case for legislation, which was put forward very persuasively by the Archbishop of Canterbury, is briefly this. The existing law provides machinery by which the distribution of obscene publications can be prevented. It is generally agreed that such machinery is necessary, at any rate for the protection of children and young persons. It is for the court to decide whether a particular publication is obscene, but there is no statuary definition of obscenity and it has to be regarded, as result of judicial decisions, as being restricted to matter related to sex. These objectionable comics are not obscene within the meaning of the existing law, but they are just as harmful, if not more harmful to children and young persons as publications which are obscene, and the courts ought to be given the same power to prevent their circulation as they have to prevent the circulation of obscene publications. It would be no more difficult for a court to decide whether a publication was harmful because of its excessive emphasis on horror, crime or cruelty than it is to decide whether a publication is obscene.