Extract from a printed account by the London Corresponding Society on the arrest of Thomas Hardy, 12 May 1794, Catalogue ref: TS 24/3/33

Transcript

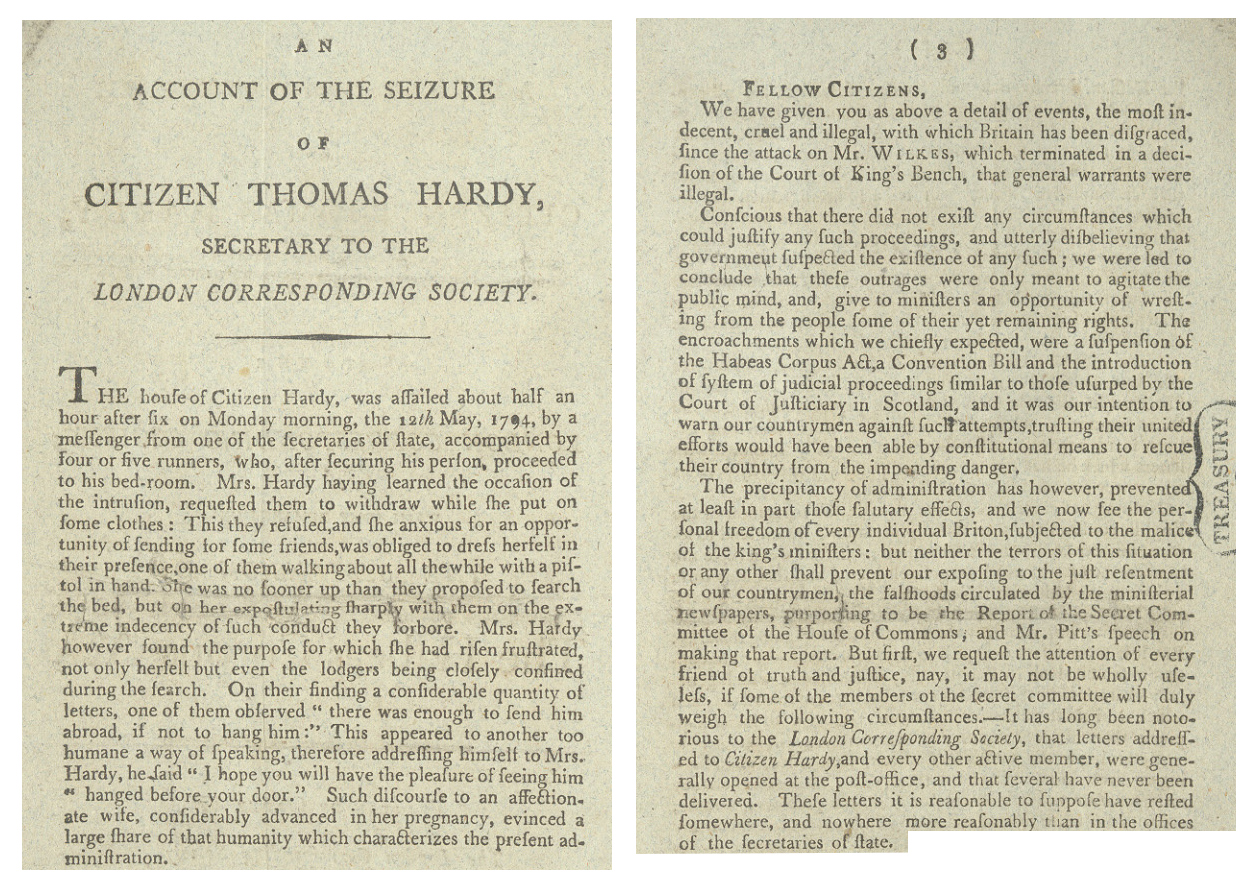

AN

ACCOUNT OF THE SEIZURE

OF

CITIZEN THOMAS HARDY,

SECRETARY TO THE

LONDON CORRESPONDING SOCIETY.

The house of Citizen Hardy, was assailed [attacked] about half an hour after six on Monday morning, the 12th May, 1794, by a messenger from one of the secretaries of state, accompanied by four or five runners [policemen], who, after securing his person, proceeded to his bed-room. Mrs. Hardy having learned the occasion of the intrusion, requested them to withdraw while she put on some clothes: This they refused, and she anxious for an opportunity of sending for some friends, was obliged to dress herself in their presence, one of them walking about all the while with a pistol in hand. She was no sooner up than they proposed to search the bed, but on her expostulating [protesting] sharply with them on the extreme indecency of such conduct they forebore [held back]. Mrs Hardy however found the purpose for which she had risen frustrated, not only herself but even the lodgers being closely confined during the search. On their finding a considerable quantity of letters, one of them observed “there was enough to send him abroad, if not to hang him:” [enough evidence to convict him and transport him from England]. This appeared to another too humane a way of speaking, therefore addressing himself to Mrs. Hardy, he said “I hope you will have the pleasure of seeing him “hanged before your door.” Such discourse to an affectionate wife, considerably advanced in her pregnancy, evinced [revealed] a large share of that humanity which characterizes the present administration. …

FELLOW CITIZENS

We have given you as above a detail of events, the most indecent, cruel and illegal, with which Britain has been disgraced, since the attack on Mr. WILKES, which terminated in a decision of the Court of King’s Bench, that general warrants were illegal.

Conscious that there did not exist any circumstances which could justify any such proceedings, and utterly disbelieving that government suspected the existence of any such; we were led to conclude that these outrages were only meant to agitate the public mind, and give to ministers an opportunity of wresting [taking] from the people some of their yet remaining rights. The encroachments [limitations] which we chiefly expected, were a suspension of the Habeas Corpus Act, a Convention Bill and the introduction of system of judicial proceedings similar to those usurped by the Court of Justiciary in Scotland, and it was our intention to warn our countrymen against such attempts, trusting their united efforts would have been able by constitutional means to rescue their country from the impending danger.

The precipitancy [hasty action] to administration has however, prevented at least in part those salutary [improving] effects, and we now see the personal freedom of every individual Briton, subjected to the malice of the king’s ministers: but neither the terrors of this situation or any other shall prevent our exposing to the just resentment of our countrymen, the falsehoods circulated by the ministerial newspapers, purporting [claiming] to be the Report of the Secret Committee of the House of Commons, and Mr. Pitt’s [WiIliam Pitt the Younger] speech on making that report. But first, we request the attention of every friend of truth and justice, nay, it may not be wholly useless, if some of the members of the secret committee will duly weigh the following circumstances. – It has long been notorious to the London Corresponding Society, that letters addressed to Citizen Hardy, and every other active member, were generally opened at the post-office, and that several have never been delivered. These letters it is reasonable to suppose have rested somewhere, and nowhere more reasonably than in the offices of the secretaries of state.

Thomas Hardy, founder of the London Corresponding Society and eleven other leading radicals who demanded political reform were arrested. Hardy was taken to jail and later interrogated by a committee that included the Prime Minister William Pitt and some cabinet ministers. Soon after, Parliament passed a bill that suspended ‘habeas corpus’ and allowed the government to imprison all twelve men in the Tower of London without formal charge in a court for several months.

- In what manner was Thomas Hardy arrested according to this account?

- The document mentions ‘the attack on Mr Wilkes’ – use the Background to find out more.

- According to this account, how did the government limit political rights in the 1790s?

- Why do you think Thomas Hardy is described as ‘Citizen Hardy’ and readers are called ‘Fellow citizens’ in this source?

- Does this source infer why the government feared radicals like Thomas Hardy?

- How would you describe the tone and attitude of this source?

- Thomas Hardy was found not guilty of treason due to lack of evidence. Is this verdict surprising? Read the article in the External links about the details of his trial.