Extract from an official report on the evacuation from Hong Kong, 1940, Catalogue ref: CO 323/1808/6

In July 1940, as the threat of a Japanese invasion intensified, more than 3,000 British women and children were evacuated from Hong Kong and shipped to Australia, via Manila in the Philippines. In addition, over 9,000 people were evacuated from Malaya. Very few of the evacuees from the colonies were sent to Britain. Most were sent to other nearby colonies and dominions such as Australia, New Zealand, India and South Africa. It was thought that this was much safer than travelling to Britain and allowed the ships to be used to move troops.

Transcript

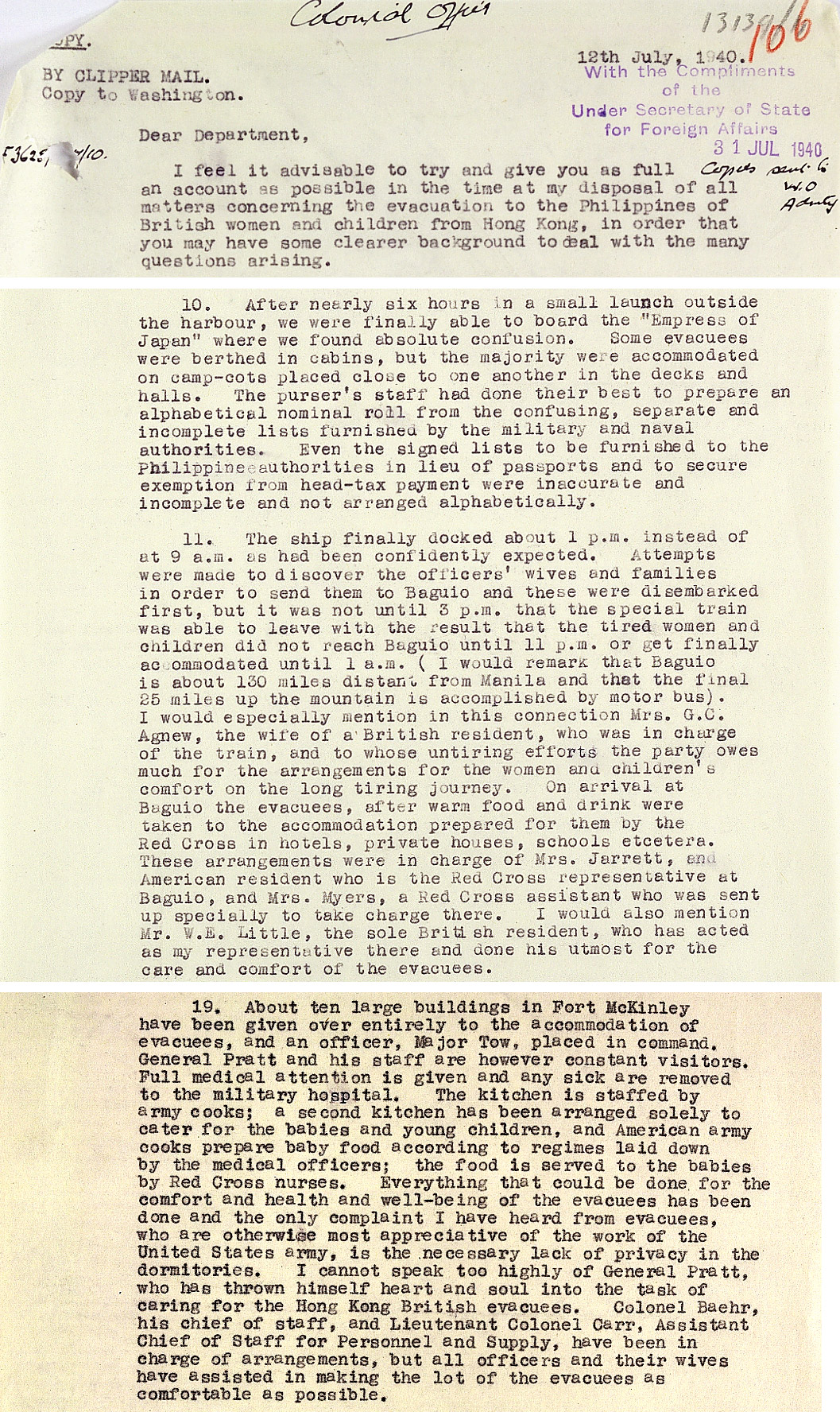

12th July, 1940.

With the Compliments of the Under Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs 31 Jul 1940

COPY.

BY CLIPPER MAIL.

Copy to Washington.

Dear Department,

I feel it advisable to try and give you as full an account as possible in the time at my disposal of all matters concerning the evacuation to the Philippines of British women and children from Hong Kong, in order that you may have some clearer background to deal with the many questions arising.

…

10. After nearly six hours in a small launch outside the harbour, we were finally able to board the “Empress of Japan” where we found absolute confusion. Some evacuees were berthed in cabins, but the majority were accommodated on camp-cots placed close to one another in the decks and halls. The purser’s staff had done their best to prepare an alphabetical nominal roll from the confusing, separate and incomplete lists furnished by the military and naval authorities. Even the signed lists to be furnished to the Philippine authorities in lieu of passports and to secure exemption from head-tax payment were inaccurate and incomplete and not arranged alphabetically.

11. The ship finally docked about 1 p.m. instead of at 9 a.m. as had been confidently expected. Attempts were made to discover the officers’ wives and families in order to send them to Baguio and these were disembarked first, but it was not until 3 p.m. that the special train was able to leave with the result that the tired women and children did not reach Baguio until about 11 p.m. or get finally accommodated until 1 a.m. (I would remark that Baguio is about 130 miles distant from Manila and that the final 25 miles up the mountain is accomplished by motor bus). I would especially mention in this connection Mrs. G.C. Agnew, the wife of a British resident, who was in charge of the train, and to whose untiring efforts the party owes much for the arrangements for the women and children’s comfort on the long tiring journey. On arrival at Baguio the evacuees, after warm food and drink were taken to the accommodation prepared for them by the Red Cross in hotels, private houses, schools etcetera. These arrangements were in charge of Mrs. Jarrett, an American resident who is the Red Cross representative at Baguio, and Mrs. Myers, a Red Cross assistant who was sent up specially to take charge there. I would also mention Mr. W.E. Little, the sole British resident, who has acted as my representative there and done his utmost for the care and comfort of the evacuees.

…

19. About ten large buildings in Fort McKinley have been given over entirely to the accommodation of evacuees, and an officer, Major Tow, placed in command. General Pratt and his staff are however constant visitors. Full medical attention is given and any sick are removed to the military hospital. The kitchen is staffed by army cooks; a second kitchen has been arranged solely to cater for the babies and young children, and American army cooks prepare baby food according to regimes laid down by the medical officers; the food is served to the babies by Red Cross nurses. Everything that could be done or the comfort and health and well-being of the evacuees has been done and the only complaint I have heard from evacuees, who are otherwise most appreciative of the work of the United States army, is the necessary lack of privacy in the dormitories. I cannot speak too highly of General Pratt, who has thrown himself heart and soul into the task of caring for the Hong Kong British evacuees. Colonel Baehr, his chief of staff, and Lieutenant Colonel Carr, Assistant Chief of Staff for Personnel and Supply, have been in charge of arrangements, but all officers and their wives have assisted in making the lot of the evacuees as comfortable as possible.