Extracts from a file entitled ‘Colonial Office working party on the recruitment of West Indians for United Kingdom industries’, 1948-1949. Catalogue ref: LAB 26/226

Contains original language used at the time which is not appropriate today.

- What were the aims of the working party?

- What economic problems existed in the ‘West Indian Islands economies’?

- How successful was the employment of immigrants 1947-1948?

- What was the ‘Westward Ho scheme?

- What concerns did the working party have about the difference between European workers and colonial citizens?

Transcript

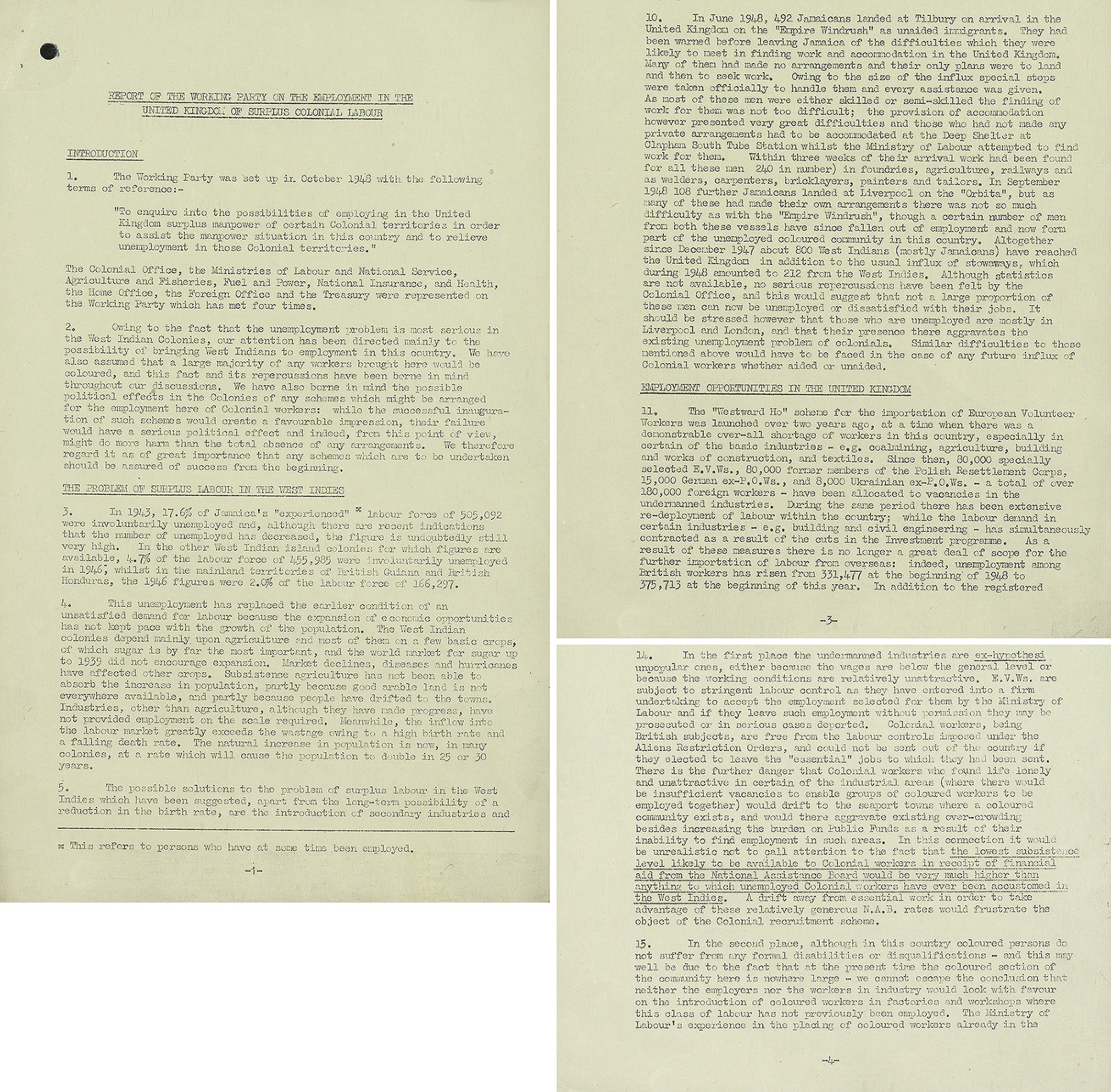

REPORT OF THE WORKING PARTY ON THE EMPLOYMENT IN THE UNITED KINDGOM OF SURPLUS COLONIAL LABOUR

INTRODUCTION

The working party was set up in October 1948 with the following terms of reference:

“To enquire into the possibilities of employing in the United Kingdom surplus manpower of certain Colonial territories in order to assist the manpower situation in this country and to relieve unemployment in those Colonial territories.”

The Colonial Office, the Ministries of Labour and National Service, Agriculture and Fisheries, Fuel and Power, National Insurance, and Health, the Home Office, the Foreign Office and the Treasury were represented on the Working Party which has met four times.

- Owing to the fact that the unemployment problem is most serious in the West Indian Colonies, our attention has been directed mainly to the possibility of bringing West Indians to employment in this country. We have also assumed that a large majority of any workers brought here would be coloured, and this fact and its repercussions have been borne in mind throughout our discussions. We have also borne in mind the possible political effects in the Colonies of any schemes which might be arranged for the employment here of Colonial workers: while the successful inauguration of such schemes would create a favourable impression, their failure would have a serious political effect and indeed from this point of view, might do more harm than the total absence of any arrangements. We therefore regard it as of great importance that any schemes which are to be undertaken should be assured of success from the beginning.

THE PROBLEM OF SURPLUS LABOUR IN THE WEST INDIES

- In 1943, 17.6% of Jamaica’s “experienced*” labour force of 505,092 were involuntarily unemployed and, although there are recent indications that the number of unemployed has decreased, the figure is undoubtedly still very high. In the other West Indian Island colonies for which figures are available, 4.7% of the labour force were involuntarily unemployed in 1946; whilst in the mainland territories of British Guiana and British Honduras, the 1946 figures are 2.0% of the labour force of 166, 297.

- This unemployment has replaced the earlier condition of an unsatisfied demand for labour because the expansion of economic opportunities has not kept pace with the growth of population. The West Indian colonies depend mainly upon agriculture and most of them on a few basic crops of which sugar is by far the most important, and the world market for sugar up to 1939 did not encourage expansion. Market decline, diseases, and hurricanes have affected other crops, Subsistence agriculture has not been able to absorb the increase in population, partly because good arable land is not everywhere available, and partly because people have drifted to the towns. Industries, other than agriculture, although they have made progress, have not provided employment on the scale required. Meanwhile, the inflow into the labour market greatly exceeds the wastage owing to a high birth rate and falling death rate. The natural increase in population is now, in many colonies, at a rate which will cause the population to double in 25 or 30 years.

- The possible solutions to the problem of surplus labour in the West Indies which have been suggested, apart from the long-term possibility of a reduction in the birth rate, are the introduction of secondary industries and

*This refers to persons who have at some time been employed.

…

- In June 1948, 492 Jamaicans landed at Tilbury on arrival in the United Kingdom on the “Empire Windrush” as unaided immigrants. They had been warned before leaving Jamaica of the difficulties which they were likely to meet in finding work and accommodation in the United Kingdom. Many of them had made no arrangements and their only plans were to land and then to seek work. Owing to the size of the influx special steps were taken to handle them and every assistance was given. As most of these men were either skilled or semi-skilled the finding of work for them was not too difficult; the provision of accommodation however presented very great difficulties and those who had not made any private arrangements had to be accommodated at the Deep Shelter at Clapham South Tube Station whilst the Ministry of Labour attempted to find work for them. Within three weeks of their arrival work had been found for all these men 240 in number) in foundries, agriculture, railways and as welders, carpenters, bricklayers, painters and tailors. In September 1948, 108 further Jamaicans landed at Liverpool o the “Orbita”, but as many of these had made their own arrangements there was not so much difficulty as with the “Empire Windrush”, though a certain number of men from both these vessels had fallen out of employment and now form part of the unemployed coloured community in this country. Although since December 1947 about 800 West Indians (mostly Jamaicans have reached the United Kingdom in addition to the usual influx of stowaways, which during 1948 amounted to 212 from the West Indies. Although statistics are not available, no serious repercussions have been felt by the Colonial Office, and this would suggest that not a large proportion of these men can now be unemployed or dissatisfied with their jobs. It should be stressed however that those who are unemployed are mostly in Liverpool and London, and that their presence there aggravates the existing unemployment problem of colonials. Similar difficulties to those mentioned above would have to be faced in the case of any future influx of Colonial Workers whether aided or unaided.

EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITIES IN THE UNITED KINGDOM

- The “Westward Ho” scheme for the importation of European Volunteer Workers was launched over two years ago, at a time when there was a demonstrable shortage of workers I this country, especially in certain of the basic industries- e.g. Coalmining, agriculture, building and works of construction, and textiles. Since then, 80,000 specially selected E.V.W.s, 80,000 former members of the Polish Resettlement Corps,15, 000 German ex-P.O.W.s and 8,000 Ukrainian ex-P.O.W.s- a total over 180,000 foreign workers- have been allocated to vacancies in the undermanned industries. During the same period there has been extensive re-deployment of labour within the country; while the labour demand in certain industries-e.g. building and civil engineering-has simultaneously contracted as a result of the cuts in the Invest Programme. As a result of these measures there is no longer a great deal of scope for the further importation of labour from overseas: indeed, unemployment among British workers has risen from 331,477 at the beginning of 1948 to 375,713 at the beginning of this year.

…

- In the first place the undermanned industries are ex-hypothesi [supposedly] unpopular ones, either because the wages are below the general level or because the working conditions are relatively unattractive. E.V.Ws. are subject to stringent labour control as they have entered into a firm undertaking to accept the employment selected for them by the Ministry of Labour and if they leave such employment without permission they may be prosecuted or in serious cases deported. Colonial workers, being British subjects, are free from the labour control imposed under the Aliens Restrictions Orders and could not be sent out of the country if they elected to leave “essential” jobs to which they had been sent. There is further danger that Colonial workers who found life lonely and unattractive in certain of the industrial areas (where there would be insufficient vacancies to enable groups of coloured workers to be employed together) would drift to the seaport towns where a coloured community exists, and would there aggravate existing over-crowding besides increasing the burden on Public Funds as a result of their inability to find employment in such areas. In this connection it would be unrealistic not to call attention to the fact that the lowest subsistence level likely to be available to Colonial workers in receipt of financial aid from the National Assistance Board would be very much higher than anything to which unemployed Colonial workers have ever been accustomed in the West Indies. A drift away from essential work in order to take advantage of these relatively generous N.A.B. rates would frustrate the object of the Colonial Settlement Scheme.

- In the second place, although in this country coloured persons do not suffer from any formal disabilities or disqualifications-and this may well be due to the fact that at the present time the coloured section of the community here is nowhere large-we cannot escape the conclusion that neither the employers or the workers in industry would look with favour on the introduction of coloured workers in factories and workshops where this class of labour has not previously been employed. The Ministry of Labour’s experience in the placing of coloured workers already in the

….