This document comes from a file entitled ‘The Commonwealth Immigrants Act 1968: Qualification for entry into the UK’. Catalogue ref: FCO 50/329

It is a summary from the British High Commissioner in Kenya sent to the Secretary of State for Commonwealth Affairs about the impact of the new Commonwealth Immigrant Act on Kenya, 21 May 1968.

The British colonial rule came to an end in 1963 when an ethnic Kenyan majority government was elected and the independent Republic of Kenya formed in 1963.

In 1968, the Labour government passed the Commonwealth Immigration Act, which restricted UK citizenship to those born in the UK and their children or grandchildren. Those living in the ex-colonies without a direct family connection to the UK were no longer entitled to enter the country.

- Find out the terms of the Commonwealth Immigration Act 1968.

- Find out how and why Kenya became independent from Britain.

- How did the 1968 Common Immigration Act affect Kenya, according to the British High Commissioner?

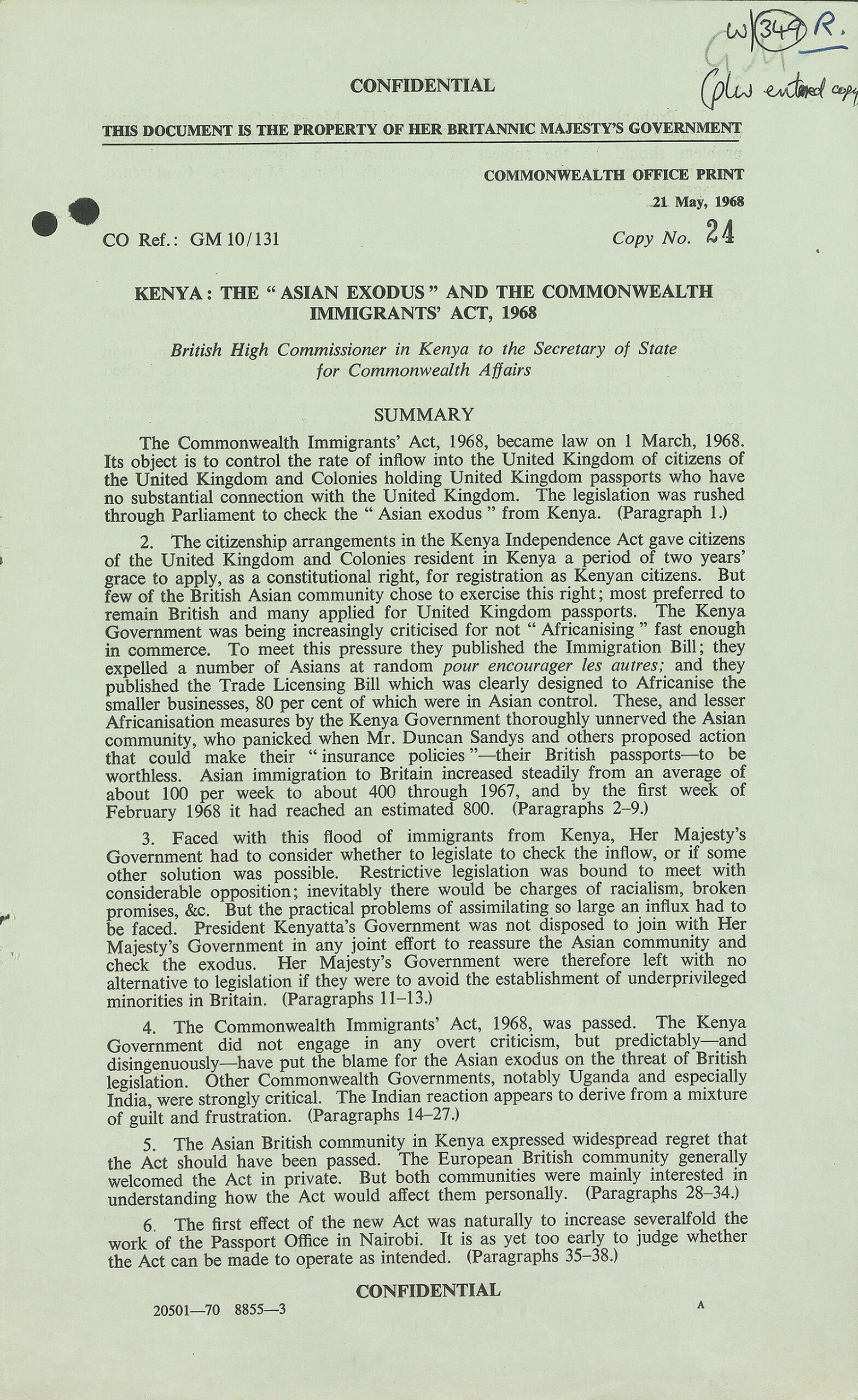

Transcript

COMMONWEALTH OFFICE PRINT

21 May,1968

KENYA: THE “ASIAN EXODUS” AND THE COMMONWEALTH IMMIGRANTS’ ACT, 1968

British High Commissioner in Kenya to the Secretary of State for Commonwealth Affairs

SUMMARY

The Commonwealth Immigrants’ Act, 1968, became law on 1 March 1968. Its object is to control the rate of inflow into the United Kingdom of citizens of the United Kingdom and Colonies holding United Kingdom passports who have no substantial connection with the United Kingdom. The legislation was rushed through Parliament to check the “Asian exodus” from Kenya. (Paragraph 1.)

- The citizenship arrangements in the Kenya Independence Act gave citizens of the United Kingdom and the Colonies resident in Kenya a period of two years’ grace to apply, as a constitutional right, for registration as Kenyan citizens. But few of the British Asian community chose to exercise this right; most preferred to remain British and many increasingly criticised for not “Africanising” fast enough in commerce. To meet this pressure they published the Immigration Bill; they expelled a number of Asians at random, pour encourager les autres [encourage the others] and they published the Trade Licnesing Bill which was clearly designed to Africanise the smaller businesses, 80% of which were in Asian control. These, and lesser Africanisation measures by the Kenyan Government thoroughly unnerved the Asia community, who panicked when Mr. Duncan Sandys and others proposed action that could make their “insurance policies”- their British passports- to be worthless. Asian immigration to Britain increased steadily from an average of about 100 per week to about 400 through 1967, and by the first week of February 1968 it had reached an estimated 800. (Paragraphs 2-9).

- Faced with this flood of immigrants from Kenya, Her Majesty’s Government had to consider whether to legislate to check the inflow, or if some other solution was possible. Restrictive legislation was bound to meet with considerable opposition, inevitably there would be charges of racialism, broken promises etc. But the practical problems of assimilating so large an influx had to be faced. President Kenyatta’s Government was not disposed to join with Her Majesty’s Government in any joint effort to reassure the Asian community and check the exodus. Her Majesty’s Government was therefore left with no alternative to legislation if they were to avoid the establishment of underprivileged minorities in Britain. (Paragraphs 11-13.)

4.The Commonwealth Immigrants Act was passed. The Kenya Government did not engage in any overt criticism, but predictably-and disingenuously-have put the blame for the Asian exodus on the threat of British legislation. Other Commonwealth Governments, notably Uganda and especially India, were strongly critical. The Indian reaction appears to derive from a mixture of guilt and frustration. (Paragraphs 14-17.)

- The Asian British Community in Kenya expressed widespread regret that the Act should have been passed. The European British Community generally welcomed the Act in private. But both communities were mainly interested in understanding how the Act would affect them personally. (Paragraphs 28-34.)

- The first effect of the new Act was naturally to increase sevenfold the work of the passport Office in Nairobi. It is as yet too early to judge whether the Act can be made to operate as intended as intended. (Paragraphs 35-38.)

CONFIDENTIAL