Newspaper article from the Express and Star [Wolverhampton] 9 August 1956. Catalogue ref: AST 7/1125

Contains original language used at the time, which is not appropriate today.

- Why was this article was written?

- What does it reveal about the difficulties of finding decent accommodation and jobs for some Jamaicans?

- What does the article reveal about attitudes in British society towards immigration at that time?

Transcript

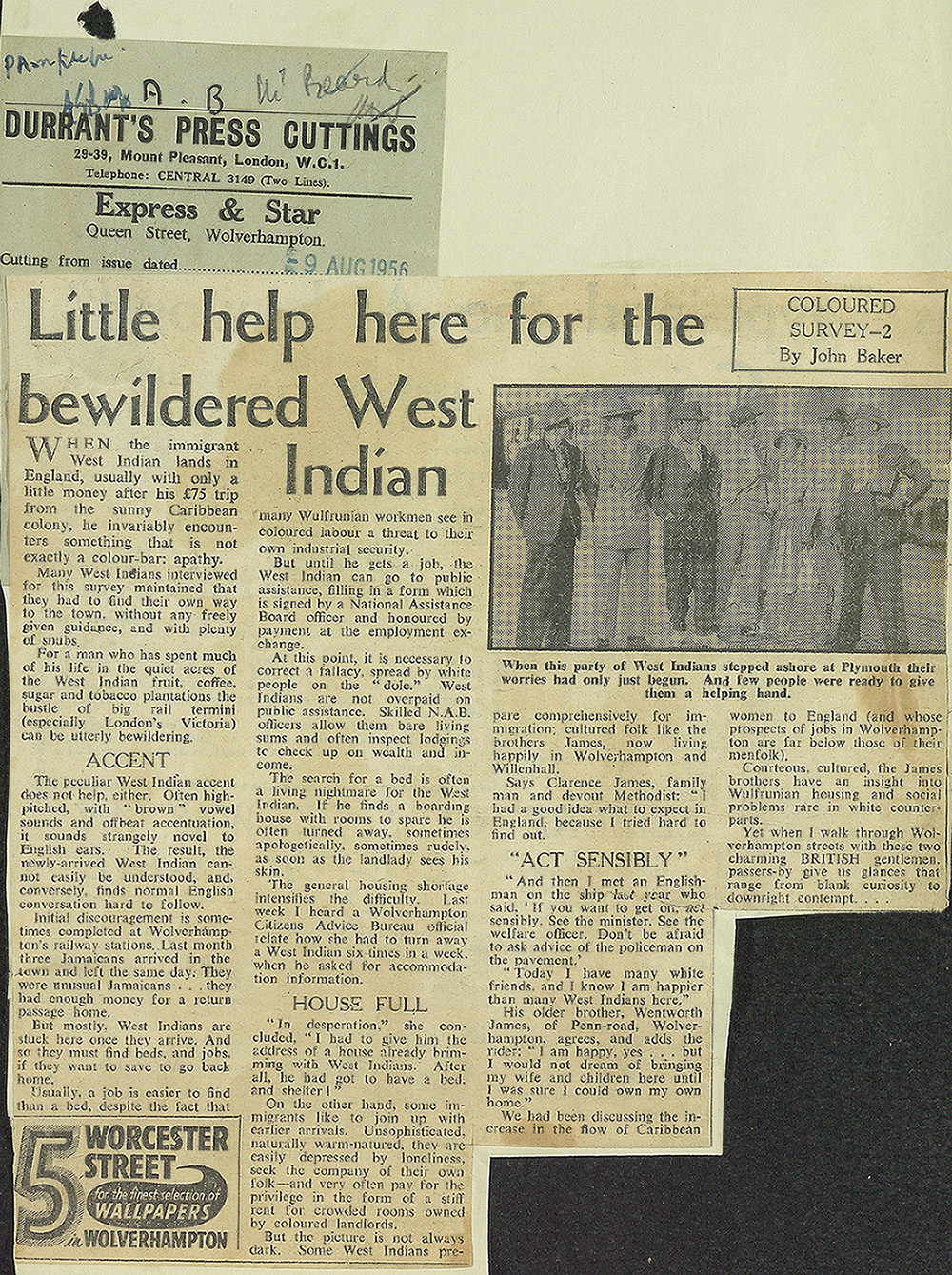

Caption for the photo:

When this party of West Indians stepped ashore at Plymouth their worries had only just begun. And few people were ready to give them a helping hand.

Little help here for the bewildered West Indian Coloured Survey-2 by John Baker

When the immigrant West Indian lands in England, usually with only a little money after his £75 trip from the sunny Caribbean colony, he invariably encounters something that is not exactly a colour bar: apathy.

Many West Indians interviewed for this survey maintained that they had to find their own way to the town without any freely given guidance and with plenty of snubs.

For a man who has spent much of his life in the quiet acres of the West Indian fruit, coffee, sugar, tobacco plantations the bustle of big rail termini (especially London’s Victoria) can be utterly bewildering.

ACCENT

The peculiar West India accent does not help either. Often high-pitched, with “brown” vowel sounds and offbeat accentuation, it sounds strangely novel to English ears. The result, the newly arrived West Indian cannot easily be understood, and conversely, finds normal English conversation hard to follow.

Initial discouragement is sometimes completed at Wolverhampton’s railway stations. Last month three Jamaicans arrived in the town and left the same day… they had enough money for a return passage home.

But mostly, West Indians are stuck here once they arrive. And so, they must find beds, and jobs, if they want to save to go back home.

Usually a job is easier to find than a bed, despite the fact that many Wulfrunian [person from Wolverhampton] workmen see in coloured labour a threat to their own industrial security.

But until he gets a job, the West Indian can go to public assistance, filling in a form which is signed by a National Assistance Board officer and honoured by payment at the employment exchange.

At this point, it is necessary to correct a fallacy, spread by white people on the “dole”, West Indians are not overpaid on Public Assistance. Skilled N.A.B officers allow them bare living sums and often inspect lodgings to check up on wealth and income.

The search for a bed is often a living nightmare for the West Indian. If he finds a boarding house with rooms to spare he is often turned away, sometimes rudely, as soon as the landlady sees his skin.

The general housing shortage intensifies the difficulty. Last week I heard a Wolverhampton Citizen’s Advice Bureau official relate how she had to turn away a West Indian six times in a week, when he asked for accommodation.

HOUSE FULL

“In desperation”, she concluded, “I had to give him the address of a house already brimming with West Indians. After all, he had got to have a bed and shelter!”

On the other hand, some immigrants like to join up with earlier arrivals. Unsophisticated, naturally warm-natured, they are easily depressed by loneliness, seek the company of their own folk-and very often pay for the privilege in the form of a stiff rent for crowded rooms owned by coloured landlords.

But the picture is not always dark. Some West Indians prepare comprehensively for immigration; cultured folk like the brothers James, now living happily in Wolverhampton and Willenhall.

Says Clarence James, family man and devout Methodist: “I had a good idea what to expect in England because I tried hard to find out”

“ACT SENSIBLY”

“And then I met an Englishman on the ship last year who said, “If you want to get on, act sensibly. See the Minister. See the Welfare Officer. Don’t be afraid to ask the advice of the policeman on the pavement.”

“Today I have many white friends, and I know I am happier than many West Indians here.”

His older brother, Wentworth James, of Penn-road, Wolverhampton, agrees, and adds the rider: “I am happy, yes… but I would not bring my wife and children here until I was sure that I could own my own home.”

We have been discussing the increase in the flow of Caribbean women to England (and whose prospects of jobs in Wolverhampton are far below those of their menfolk).

Courteous, cultured, the James brothers have an insight into Wulfrunian housing and social problems rare in white counterparts.

Yet when I walk through Wolverhampton streets with these two charming BRITISH gentlemen, passers-by give us glances that range from blank curiosity to downright contempt.