Main section

Tabs Navigation

Tabs

Foreword

On 29 June 2022, the Law of Property Act 1922 celebrated its centenary. This legislation had a profound impact on land law in England and Wales.

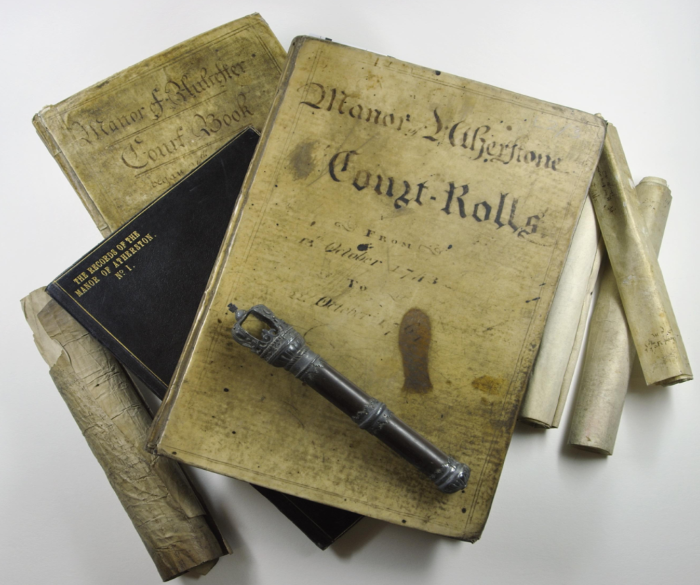

Before 1922, a form of land ownership known as ‘copyhold’ was extremely common across the lands of manors. It was called copyhold because the transfer of the tenancy was written in a manorial court roll, and a copy was handed to the tenant. The 1922 Act abolished copyhold tenure and converted the majority of copyholds into freeholds, something that we are all familiar with today.

The records of copyhold tenure had to be preserved after the changes brought about by the 1922 legislation so that people could prove they held a title to what was former copyhold land. Indeed, the 1922 Act introduced a statutory right to access the original manorial court documents. My predecessor as Master of the Rolls, Lord Hanworth (formerly Sir Ernest Pollock), issued the first Manorial Document Rules in 1926 to give legal protection to these records. At the same time, the Master of the Rolls established the Manorial Documents Register for England and Wales to record both the ownership and the location of manorial documents.

Originally, the Manorial Documents Register was used by the legal profession to trace copyhold records for their clients. Nowadays, as wide range of people access manorial documents for the wealth of information that they contain about the lives of ordinary people across the centuries.

Since the 1920s, the Manorial Documents Register has developed enormously. The National Archives, which maintains the register on my behalf, has led a 30-year programme to improve the Manorial Documents Register and make it available online. I am grateful to all of our partners, including funders, universities, record offices and private owners, who have helped make this huge task possible. They have, by their tireless efforts, unlocked a wealth of insights into our past.

The Right Honourable Sir Geoffrey Vos,

Master of the Rolls

What is a manor?

The manor in England and Wales has a long and complex history. In general, manors were landed estates, held and run by their lords, with dependent tenants living on the land. A manor could be small or large, compact or scattered across a wider area, but it was administered as a single unit. The lord had jurisdiction in the manor and held various rights, including the ability to levy marriage and death duties on unfree tenants. The manor’s ‘private’ court was at the heart of the manorial system and enforced the manor’s customs. The court decided matters such as rights to common land and wasteland, the transfer of property, the conditions of tenancy, the making of byelaws and the appointment of minor officials.

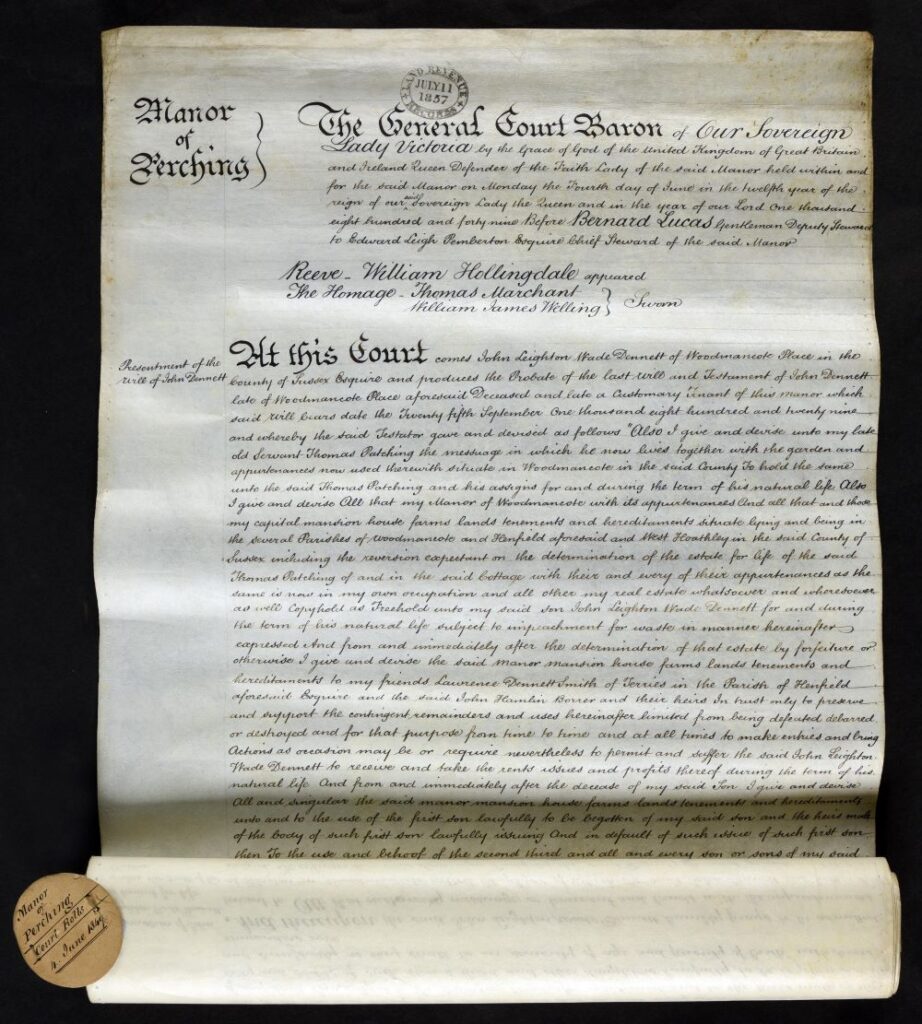

There were two main types of manorial courts – the ‘court baron’ and the ‘court leet’. The court baron upheld the customs of the manor, enforced the payment of dues, and managed the terms of land tenancy. The court leet, held twice a year, was the lowest court of royal civil and criminal jurisdiction, which had been given to local lords to run. It dealt with issues such as petty offenses (e.g. assault) and road maintenance, while handing more serious issues over to higher courts. The manorial court was normally run by the lord’s steward and was held within the manor, perhaps in the hall of the manor house, an inn, or a purpose-built courthouse. The importance of manor courts declined over time but some manor courts were still active in the 20th century, and a few remain so today.

What are manorial documents?

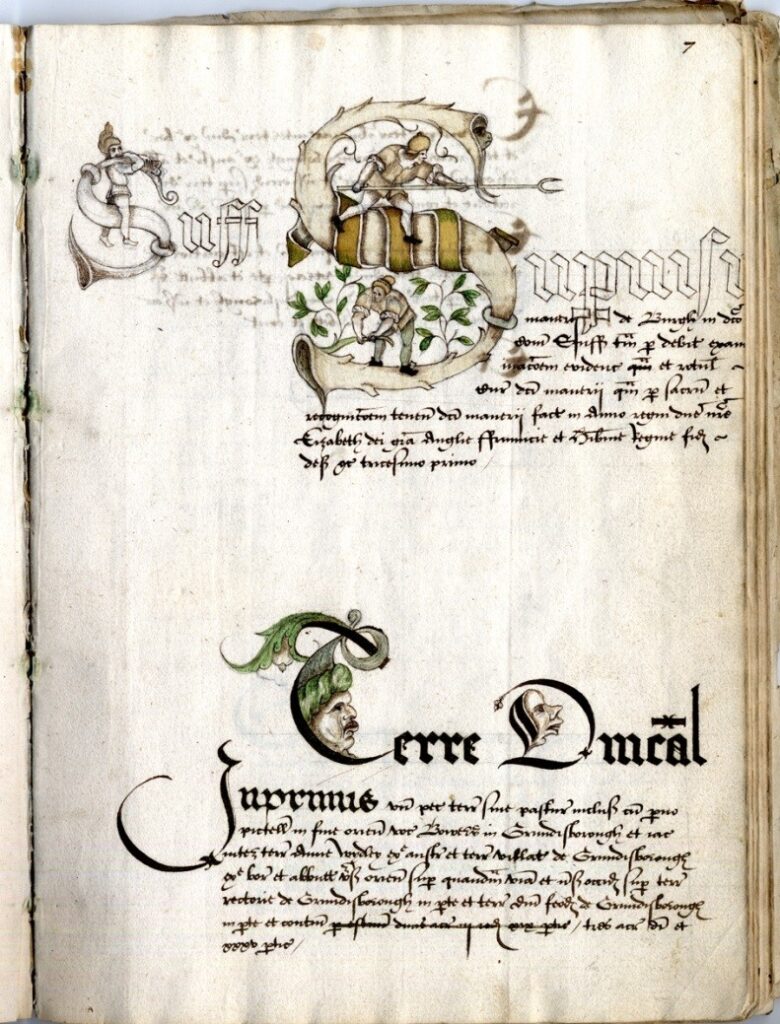

These documents are the administrative records created by the manorial system. They are legally defined as ‘court rolls, surveys, maps, terriers, documents and books of every description relating to the boundaries, wastes, customs or courts of a manor’ excluding title deeds. These records date back to the 12th century but survive in increasingly large numbers from the 14th to the 20th century.

Discoveries using manorial documents

Heriots

A heriot was a death levy that a copyhold tenant’s heir had to pay before they could take over the former tenant’s holding. It usually took the form of the tenant’s best beast. Kent Archives holds an unusual collection of hair from different animals, serving as a record of the payments made. All these animals were chosen as heriots and handed over to the lord of the manor of Yalding between 1845 and 1864. Sometimes a heriot was a money or in-kind payment. When a Robert Adams died in the manor of Penkridge Deanery, Staffordshire, in 1805, the executors of his will were asked for four silver spoons, which were later discovered in a box of court papers.

Wreck records

Some manor lords with coastal manors held the ‘right of wreck’, entitling them to cargo and flotsam washed ashore from shipwrecks. The manor allowed the finder of a wreck to claim one half of the cargo’s value, provided that it was recorded in the manor court. In 1385, one person paid ten pence for his half-share of the clothes off a drowned sailor on the Sizewell coast in Suffolk. In the manor of Winnianton, Cornwall, two tenants risked secretly carrying off all 54 gallons of wine from a wreck for themselves. However, the empty cask was presented as evidence at court and the lord handed them hefty fines.

Another interesting wreck find in the manor of Methleigh was an elephant’s ‘tooth’ (tusk). Kresen Kernow in Cornwall holds a document written by the manor’s steward in 1765, which mentions a French ship thrown ashore within the manor. The commercial trade in ivory was nearing its peak at this time and manorial documents can provide us with an excellent snapshot of the historical trade in goods.

The value of manorial documents

Manorial documents provide a snapshot of daily life for ordinary people from the 14th to the 20th century, making these records an important source for local, social, family and economic history. Researchers use manorial records to study a wide variety of subjects, such as land ownership, buildings, archaeology, crime, diet, gender, welfare, landscape and agriculture. Some manors contained markets, fairs and even towns, and their records contain details of commercial activity, urban growth and industrial developments.

These records are full of information about the local community, including the use of land, the transfer of property among tenants, the election of local officials and the resolution of disagreements. They can also tell us a great deal about the social structure of the manor’s community, both men and women, from the relatively wealthy to the lowest members of the social hierarchy.

Manorial documents are therefore extremely valuable in capturing the experience of a broad range of people. Manorial documents can also show us how life differed across the country as population density, tenancy type and customs varied from manor to manor. Even inheritance customs varied, with the land either going to the oldest child (primogeniture), to the youngest, or being split equally between all offspring. Manorial documents record the activities of many ordinary people so can be very useful for researching named individuals. Court rolls mainly deal with manorial tenants who had to attend the court and who were sometimes minor officials or jurors (potentially a sign of prominence within the community). They also reference non-tenants who were involved in private legal action or had flouted the manor’s customs, such as fishing illegally.

Manorial surveys and rentals both name individual tenants. Surveys provided an overall view of the manor at a given time, listing the tenants and their holdings with a record of the rents, labour services and payments owed to the lord. Rentals contain details of the land that each tenant held, the amount of rent paid and the type of tenure. Freehold tenants are rarely mentioned in court rolls so rentals may provide the only evidence of freehold ownership. Manorial accounts summarise how the manor was managed each year, including cash flows and the production of grain and livestock.

Researching with manorial documents

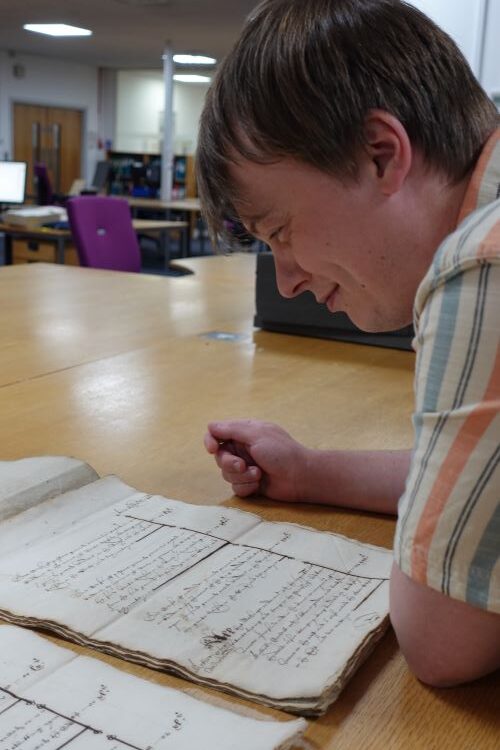

How do I read manorial documents?

Formal manorial records before 1733 were written in Latin but many of the supporting documents began to change to English from the 1500s. The Commonwealth period of 1650 to 1659 is an exception where all records were written in English. Fortunately, the wording and structure of manorial documents was highly formulaic so, if your knowledge of Latin is limited, you can start with the later manorial records in English to help you learn their shared style and format. To use manorial documents, you will need to be able to read older forms of handwriting and be aware of some vocabulary from the time. However, once you are armed with this knowledge, you will be able to access a surprising amount of information. Printed and online guides to manorial documents can provide extra help with the documents’ contents, language and form over time.

How do I find the manorial documents I need?

The records for one manor alone can be held by different local record offices, privately held family estates, cathedral or college collections, and national repositories such as the British Library and The National Archives. To help with this, we have made the Manorial Documents Register available online, bringing all of this information together for you in one place.

The Manorial Documents Register

The Manorial Documents Register (MDR) is the official index of English and Welsh manorial records. You can use the register to identify manors in each county of England and Wales, and to find out which records survive from these manors. The register also provides you with the location of the documents, which could be in public or private hands. Compiled over decades, the original MDR was paper-based. However, it was difficult to update this register effectively and it needed improvements to fulfil its great potential as a resource for everyone. In 1992, The Historical Manuscripts Commission started a programme to update the register county by county and make it available online.

Since 2004, The National Archives and its partners have invested £1.4 million in the Manorial Documents Register and you can now access the entire register for England and Wales from wherever you are in the world. The online MDR is far more detailed and accurate than the original paper indexes, and you can search for manorial records by manor, parish, county, document type and date. Our county-based approach has enabled us to work with partners locally to raise the profile of manorial documents and increase funding opportunities. We’ve also worked closely with the archive services and private owners who hold the majority of the surviving manorial records and who have helped complete the online register.