The story of

Judy, the only dog registered as a prisoner of war

Judy's remarkable story is one of capture, survival and courage, and offers a unique tale of internment during the war.

Past exhibition

Great Escapes was a major exhibition at The National Archives revealing iconic and under-told stories of prisoners of war and civilian internees during the Second World War.

It is now permanently closed. Visitors were able to explore famous escape attempts such as the escape from Stalag Luft III that we know as 'the Great Escape', and British officer Airey Neave’s escape from Colditz Castle dressed as a German soldier. They could discover remarkable stories of individuals seeking escape through art, music and finding love.

Drawing on The National Archives' vast collections of wartime era documents and photographs, the exhibition featured never previously displayed records from MI9 – a highly secretive British government agency set up to help military personnel evade and escape capture. It included recently-catalogued War Office records and incredible loans from organisations including:

The exhibition let visitors glimpse the courage and ingenuity possible in desperately hard times.

Review from The Telegraph

4 stars

A revelatory insight into the prisoner-of-war experience

The Telegraph

Get a glimpse of what visitors to the exhibition could see and do while it was open.

Image 1 of 4

A bright yet plain tunnel marked the threshold to the exhibition.

Image 2 of 4

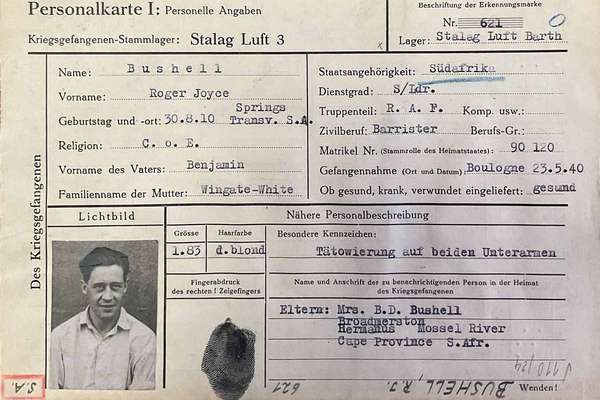

Examine the PoW card of Peter Butterworth, a Lieutenant in the Royal Navy who helped establish the camp theatre in Stalag Luft III after his capture in 1941. Catalogue reference: WO 416/53/114

Image 3 of 4

See never previously displayed records from MI9 – the highly secretive British government agency set up in 1939 to help military personnel evade and escape capture. Catalogue reference: WO 208/3268

Image 4 of 4

Read how 24-year-old Airey Neave became the first British officer to successfully escape Colditz, the infamous castle used as a Second World War prisoner of war camp. Catalogue reference: WO 208/3308

Watch

Great Escapes: Exhibition Tour

on YouTube

Watch

Great Escapes: Exhibition Tour

on YouTube

Life in Japanese captivity was brutal.

Food was scarce, disease common and punishment frequent.

Escape was next to impossible. But Ralph Goodwin managed it.

He was a prisoner in Sham Shui Po camp in Hong Kong.

On the night of 16th/17th July 1944, Goodwin slipped out from under his mosquito net, grabbed his pack and water bottle and walked out of his hut.

It was a dark and rainy night and he encountered no one on his way.

He swam to mainland China and managed to evade capture for 11 days.

Thankfully, he met up with Chinese civilians who helped him travel thousands of miles to safety.

This is an exhibition about the experiences of people from the United Kingdom and Commonwealth who fell into enemy hands during the Second World War, and those held captive by the British; how they endured their captivity, and how they endeavoured to transcend and escape it.

The Second World War broke out in 1939. It was a global struggle between the Axis forces - Nazi Germany, imperial Japan and Fascist Italy and the Allies - the British imperial and Commonwealth countries, the United States, the Soviet Union, China and France.

During its course, millions of men, women and children were taken prisoner.

Most were held in camps: Prisoner of War camps for combatants and internment camps for civilians.

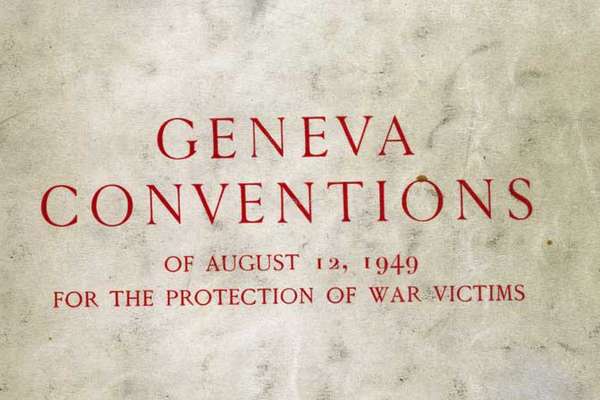

This is the Geneva Convention of 1929. It was an attempt to set a standard for the treatment of Prisoners of War, but it was not observed everywhere, and – crucially – it did not cover civilians.

Conditions in the camps could be brutal, treatment cruel and food in short supply. Even in the best circumstances, prisoners were tormented by powerlessness, boredom and simply not knowing when their captivity would end.

Many took refuge in sporting activities and theatrical productions. Most camps had libraries and religious provision.

Attempts at physical escape were a regular occurrence and acts of resistance were a part of everyday life.

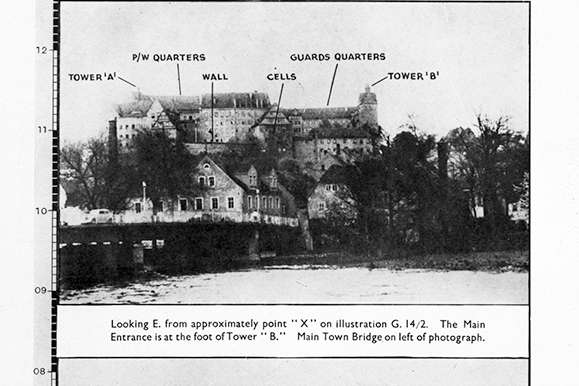

The most famous POW camp of all was Oflag IV-C: Colditz. The Germans used it to house over 800 prisoners they considered to be particularly important, dangerous or likely to escape.

Built high on a rocky outcrop in Saxony, they believed Colditz to be escape proof. They were wrong.

This is a plan of Colditz made with the help of Lieutenant Airey Neave.

On the night of January 5th, 1942, Neave knocked through the floor of the camp theatre – shown at the centre of the plan. He dropped into the guard room beneath it. He was wearing a fake German uniform and carrying forged papers.

With a fellow prisoner, a Dutch officer, Neave walked past the guards and out of the camp.

The two men took this escape route to the Swiss border. The going was hard. Neave and his companion arrived in Switzerland half-starved. But they’d done it.

He was the first British officer to escape from Colditz. After his safe return to England, Neave joined MI9, a secret department of the War Office.

It was MI9’s job to help military personnel evade capture and escape captivity.

They gathered intelligence from POWs, from concealed letters like this one from Lieutenant Peter Gardner, hidden in the middle of a postcard.

They also provided maps of escape routes.

This prototype is made of paper, later maps would be printed on silk, which is more durable.

And this hairbrush contained a hidden map, saw and compass.

But POWs also constructed their own means of escape.

The most remarkable was this, the glider known as the ‘Colditz Cock’.

The brainchild of Lieutenant Tony Rolt, it was built in an attic room in Colditz castle with improvised tools such as this saw made from floorboards and a gramophone spring.

The plan was to launch it from the roof of the castle, but the camp was liberated before it could take to the air.

This kind of ingenuity and daring also characterised attempted escapes from other camps.

Sited in what is now Poland, Stalag Luft III was built to house allied airmen.

On 29th October 1943 a hollow vaulting horse made from Red Cross boxes was carried out to the camp’s exercise yard.

Hidden inside were three men: Michael Codner, Oliver Philpot and Eric Williams.

Once in position, they broke the surface of the ground into a tunnel they had been digging for the past 114 days.

Here is Philpot recalling the moment of escape:

“We’re watching the watch carefully and when we reckoned it was, it was dark then Williams said ‘Ah, we’re breaking now.’

He shouted back to me, ‘Follow me.’

I got up to the front of the tunnel and, and there I could see the night’s sky above, and I looked up and I saw the German looking in.

He’s looking in to the camp, fortunately.

Well there’s no time to study him or anything, so I hoicked my bundles up one after another and followed them up, and then streaked across the little road, hauled myself out, streaked across the little road and in to those heavenly pine trees, which gave cover.”

Ironically, Stalag Luft III had been built on sandy ground in an attempt to make tunnelling impossible.

But the very next year it was the site of the most famous tunnel escape of them all: the so-called ‘Great Escape’.

Hundreds of men were involved: creating disguises, forging IDs and constructing three tunnels, code-named ‘Tom’, ‘Dick’ and ‘Harry’.

After waiting a week for a moonless night, on Friday 24th March, 1944, 76 men crawled through the 102 metres of tunnel ‘Harry’.

The 77th was spotted by a guard and the escape was stopped.

All but three of the men who escaped were recaptured. 50 of them were subsequently murdered by the Gestapo.

This put a stop to all further escape attempts, and those responsible for the murders were tried at the Nuremberg International Military Tribunal after the war.

The stories of both the Wooden Horse and the Great Escape were later made into celebrated films.

Peter Butterworth, the comic actor best known for the ‘Carry On’ films, auditioned for a part in The Wooden Horse.

He didn’t get it, which is ironic because in 1943 he was actually one of the camp inmates who helped cover for the escapers.

But for the most part, Butterworth sought other ways of escape. He was much admired by fellow POWs for his good humour, and he poured his energies into the camp’s theatre.

He directed and appeared in many shows that helped to lift morale while also being loud enough to cover the noise of tunnels being dug.

Such alternatives to physical escape were a tribute to prisoners’ ingenuity and fortitude of spirit and took many forms.

This is Patrick Nelson. Patrick was born in Jamaica. He spent four and half years as a POW. His friend and former lover was the painter and member of the Bloomsbury group, Duncan Grant.

In one of his many poignant letters to Grant, Nelson wrote, “I have not wasted a single day since I am in captivity.” He studied languages and the law and even sought to commune with his friend through clairvoyance.

Guy Griffiths, on the other hand, was able to combine an imaginative escape with an ingenious way of misleading his captors. He would draw these sketches of impressive, but entirely fictitious, aircraft and leave them around for the Germans to find.

Probably the most famous civilian internee was the English comic novelist PG Wodehouse. At the outbreak of war, he had been living in Le Touquet in France.

Interned in an overcrowded camp in Tost, Upper Silesia, Wodehouse took refuge from the grim conditions by writing. He completed two novels and maintained his genial public image in an article for the American ‘Saturday Evening Post’.

The nearest Wodehouse got to acknowledging the true misery of his plight was, characteristically, in a joke. “If this is Upper Silesia,” he wondered, “what on earth must Lower Silesia be like?”

But the joke turned sour when the German authorities realised Wodehouse’s propaganda value. Released from captivity, but still living in Germany, he made radio broadcasts to his fans in America, which had not yet entered the war.

It was a decision he would later regret. Widely denounced as a collaborator, Wodehouse never returned to Britain.

An altogether stranger story is that of another British civilian. Oswald Job. A shopfitter and decorator living in Paris, Job was arrested on 30th July 1940 as an enemy alien and sent to an internment camp in a suburb of the French capital. But in November 1943, he turned up in England, claiming to have escaped captivity and made his way across the Channel in secret.

His story unravelled when British intelligence officers intercepted secret correspondence with the German authorities. Job’s escape had been faked and he had been sent back to spy. He was arrested, tried for treachery, and executed.

In the years that followed the Second World War, Ronald Searle would become one of the most famous illustrators and cartoonists in the world. But in 1942 he was a 22-year-old in the Royal Engineers.

After Singapore fell to the invading Japanese army, Searle was sent to the notorious Changi Camp.

He later worked on the construction of the Thai-Burma “Death Railway” during which 16,000 men died.

Escape was impossible.

Instead, in secret, Searle would draw - using his unique talent to capture every detail of his ordeal.

As he remembered years later, “With my back to the wire, under gently swaying coconut palms, I had – for half an hour at least – transported myself to another, less sordid island.”

This is the collar of Judy the dog, the only animal to be given the official status of Prisoner of War.

Aircraftman Frank Williams found her in Gloegoer Camp in Indonesia and they formed a lifelong bond.

She was a great support to Frank, but also barked at guards when they tried to maltreat prisoners, kept snakes and scorpions at bay, and brought food for inmates.

As well as a number of POW camps, she and Frank survived a shipwreck together.

At the end of the war, Judy was awarded the PDSA Dickin medal, the equivalent of the Victoria Cross.

For civilians, physical escape from Japanese captivity was out of the question. So they sought other ways to resist and endure.

This is Margaret Dryburgh.

She was interned in Palembang Camp on the island of Sumatra in 1942.

Members hummed the sounds of different instruments, and sang a variety of hymns, including Margaret’s own composition, The Captives’ Hymn.

Margaret died in April 1945, just four months before the camp was liberated.

Douglas Ward was only two years old when he and his family were sent to Stanley Internment Camp.

His older brother attended classes in the camp but Douglas was too young.

He spent his time playing and sword fighting with the other children, visiting the beach, growing vegetables and searching the camp for food.

When the war ended, like many in the camp, Douglas and his family were sent to Australia.

Many of those interned were refugees from Nazi persecution. At one point, over 80% were Jewish.

Others had fled to Britain because of their political beliefs.

One was Margarete Klopfleisch, an art student and member of the German Communist Party.

She was sent to the Isle of Man in May 1940.

The number of internees was so great that 4,000 were transported overseas.

When her husband Peter was sent to Australia on the HMT Dunera, Margarete suffered a miscarriage.

Her trauma found expression in this sculpture, ‘Despair’.

Margarete was released in May 1941 and reunited with Peter.

The Dunera was one of five vessels that transported internees to Australia and Canada.

It had a maximum capacity of 1,500 but over 2,500 internees were crammed aboard.

Jewish refugees were forced to share the cramped conditions with Nazi and Fascist sympathisers.

One of the Jewish passengers was Heino Alexander.

He tried to cope with the experience by keeping a diary which recorded the many indignities he suffered.

The journey – through waters patrolled by German U-Boats – was extremely hazardous.

After 58 days, they arrived in Sydney.

The medical adviser who first went aboard was shocked by the conditions and the army officer in charge, Lieutenant Colonel William Scott, was court martialled.

Tragically, on 2nd July 1940, another of the ships – the SS Arandora Star – was torpedoed and sunk.

Over half of those aboard, including 470 Italians, lost their lives.

The British public was outraged and its sympathy swung behind the internees.

By December, 1941, over 8,000 had been released from captivity.

Heino Alexander was one of them. In 1948, he became a British citizen.

Camp 198 in Bridgend in Wales held German POWs.

On the night of 10th March 1945, 70 officers used a tunnel to break out of it,

the biggest mass escape in the UK.

One of the officers was Steffi Ehlert.

He and two others stole a doctor’s car.

When it wouldn’t start, four unsuspecting prison guards helped them get it going.

The escapees drove to Birmingham in search of an airport but were eventually recaptured.

But not all Germans were so eager to get home.

Heinz Fellbrich was a POW in Southampton when he met June Tull.

They fell in love and, despite the misgivings of some of her friends and family, June agreed to marry Heinz.

Many fellow POWs were invited to attend the wedding in August 1947.

Here is a picture of June and Heinz on their wedding day. You can see in the background a sign for the POW camp.

All POWs - including Heinz – had to return to the camp that night.

It was another year before Heinz and June could live together.

After his release, Heinz became a British citizen and remained in the UK for the rest of his life.

He and June had six children.

For some, returning home was a joyful occasion.

The government provided tips on how to resume a normal life.

Others struggled to adapt and reintegrate after their traumatic experiences.

Their physical and psychological suffering continued long after the war and many never spoke about what they had endured.

On 12th August 1949 a new Geneva Convention was signed.

In contrast with its predecessor, it made provision for the humane treatment of all “persons taking no active part in the hostilities”: civilians.

Never before had so many people been taken into captivity.

Millions of service personnel and hundreds of thousands of civilians spent anything from a few weeks to the entire duration of the war in confinement.

What united them all was their inspiring stories of resilience, strength, friendship, survival and hope.

This video can also be viewed on YouTube with optional closed captions. Watch "Great Escapes: Exhibition Tour" on YouTube.

The National Archives is the official archive of the UK government, and England and Wales. We are the guardians of over 1,000 years of iconic national documents.

Everyone is welcome to visit our headquarters in Kew. We put on exhibitions, events and displays and offer reading rooms giving access to our collections there.

The National Archives is located by the River Thames in Kew, 30 minutes from Central London. We offer advice on travelling to us by car, bike, train or bus.

Love Letters opens on 24 January 2026.

See our opening times.

Everyone is welcome to visit this exhibition.

We provide a warm welcome to visitors of all ages, including children and family groups.

We have a café and coffee bar provided by Maids of Honour, a historic local tea room and bakery. It has spacious indoor and outside seating and a soft play area.

On the menu is a variety of high-quality lunchtime meals, sandwiches, snacks, soft drinks, tea and coffee. Vegetarians, vegans and other dietary requirements are all catered to.

Keen to explore Second World War captives' stories? Read articles on the exhibition’s themes.

The story of

Judy's remarkable story is one of capture, survival and courage, and offers a unique tale of internment during the war.

Focus on

Discover how this guerrilla group played a significant role in opposing Japan and aiding Allied prisoners of war around Hong Kong.

The story of

Roger Bushell (1910–1944) was a pilot, prisoner of war (POW), and mastermind of the ‘Great Escape’ from Stalag Luft III in March 1944.

Record revealed

During the Second World War, some British prisoners of war were able to send secret messages and intelligence back home via creative and unusual ways.

Record revealed

This document sets out the laws its signatory nations agreed to follow around the treatment of prisoners of war, those in medical need, and civilians.

In pictures

Discover how Allied prisoners of war survived and daringly tried to escape this seemingly secure fortification.

The story of

14-year-old cabin boy John Giles Hipkin became Britain's youngest Second World War prisoner of war in 1941 after he was captured at sea.

Browse our specially selected Great Escapes books, gifts and more.