The story of

Karl Muller and the fatal lemon

When can a lemon have fatal consequences? If it proves you are, in fact, a wartime spy…

Past exhibition

MI5: Official Secrets was a major exhibition that stepped inside the hidden world of MI5 and explored the extraordinary stories behind the security of a nation.

It is now permanently closed. For the first time, MI5’s history was on display to the public, made possible through an unprecedented partnership between the Security Service and The National Archives.

Visitors explored the ever-changing world of espionage and security threats through original case files, photographs and papers, alongside the real equipment used by spies and spy-catchers over MI5’s 115-year history.

From counter-espionage and daring double-agents during the world wars, to chilling Cold War confessions and the counter-terrorism of recent times, this historic exhibition went behind the scenes of one of Britain’s most iconic institutions.

No booking required.

Review from The Daily Telegraph

5 stars

Richly detailed and wholly fascinating

The Daily Telegraph

Get a glimpse of some of the objects on display when the exhibition was open:

Image 1 of 3

The evidence that Josef Jakobs, the last person executed at the Tower of London, was a German spy. Catalogue reference: KV 2/27

Image 2 of 3

MI5's first camera, a pocket-sized 'Ensignette' made by Houghton Ltd, from 1910. On loan from the Security Service.

Image 3 of 3

The advanced radio equipment found buried in the garden of Soviet spies Helen and Peter Kroger in the 1960s. On loan from GCHQ.

Watch

MI5: Official Secrets Exhibition video tour

on YouTube

Watch

MI5: Official Secrets Exhibition video tour

on YouTube

For over 100 years, the men and women of the Security Service, better known as MI5, have worked quietly and tirelessly to protect the United Kingdom and its way of life. These ordinary people, leading extraordinary lives, have operated in secret making courageous and difficult decisions.

In partnership with MI5, The National Archives can now show you never-before-seen exhibits from MI5’s history. To go behind locked doors, to share the bustle of its corridors, the whispered confidences of its meeting rooms, to access its archive of formerly classified documents. To see at last, what were once official secrets.

In the early years of the 20th century, the United Kingdom was in the grip of spy fever. Popular fiction fed a widespread fear that a German invasion was imminent, and that the country had already been infiltrated by an army of spies.

To address these concerns, the government decided to establish a Secret Service Bureau, now known as MI5. For the first time, all the nation’s efforts to counter foreign espionage would be brought under the control of a single organisation.

At first, the Bureau had a staff of just two. Commander Mansfield Cumming, of the Royal Navy, and Captain Vernon Kell, an army officer. It was soon decided that two separate branches were needed. Cumming took charge of the Secret Intelligence Service, later MI6, to run agents abroad, while Kell became head of MI5, responsible for countering threats from subversives and foreign spies at home.

At the heart of MI5’s work in these years was its Registry. A library of hundreds of thousands of index cards and personal files on people who might pose a threat to national security. By 1918 it had grown to a million names. Its largely female staff were led by Edith Lomax, a very talented administrator.

The Home Secretary, Winston Churchill, was supportive of the Secret Service Bureau and in 1911 the Official Secrets Act passed through parliament. Over nearly the next 80 years, it would help secure the conviction of many of the most significant spies MI5 identified.

Armed with this, and with a network of contacts in the police service, MI5 braced itself for its first great test. On 4th August 1914, the United Kingdom declared war on Germany. The next day, the Home Secretary announced that 21 spies and suspected spies had been arrested in the previous 24 hours.

This claim boosted British morale, though some historians have since questioned his numbers.

One of those arrested was Karl Ernst.

From his barber’s shop on the Caledonian Road in north London, he ran a secret ‘Post Office’, connecting German intelligence to a network of spies. He was sentenced to seven years hard labour.

But the spies kept coming.

Karl Muller entered Britain in 1915, claiming to be a Russian shipping agent. The deception failed and Muller was arrested. This lemon was found in a dressing table drawer at his lodgings. Muller used the juice of the lemon to write a secret message about troop movements between the lines of this apparently innocent business letter, which was intercepted.

Intercepting and checking letters was vital to counter-espionage work, so vital that a special postal censorship department, MI9, was established. By the end of the war, it had a staff of 4,861, three quarters of them women.

MI5 struggled to find a place for itself when peace came in 1918. By the 1920s, staff numbers had dwindled from 133 to a mere 16. Their focus in these years was on the threat posed by the newly formed Soviet Union.

The Communist International, or ‘Comintern’, advocated world revolution. Those who supported it, or were suspected of doing so, within the Communist Party of Great Britain, or even the wider Labour and Trade Union movement, came under suspicion.

During the General Strike of 1926, five agents were sent to investigate reports of communist subversion in the Aldershot military base. Striking up conversations in pubs with soldiers and labourers, they failed to find any evidence of disloyalty.

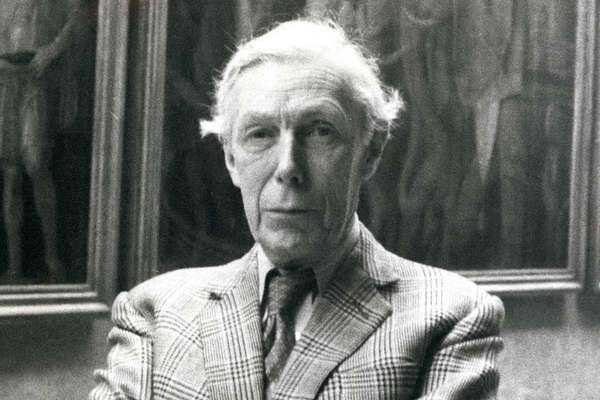

This is Maxwell Knight. Outwardly he was an eccentric, larger than life figure, and he later became a famous BBC personality. But he was also important in the intelligence community. Under his influence, MI5 came to rely less on informants, and more on agents who infiltrated suspect organisations.

In 1924, Knight himself infiltrated the British Fascisti movement. By 1933, his ‘M’ section had agents working inside both the Communist Party of Great Britain and the British Union of Fascists, a far-right party founded by Sir Oswald Mosley in 1932.

The British Union of Fascists received funding from Mussolini’s Italy, wore paramilitary style black shirt uniforms and engaged in frequent street brawls with their political enemies. Mosley was a powerful speaker, his speeches virulently antisemitic, but he was also a well-connected establishment figure.

Successive home secretaries, who regarded him as fundamentally patriotic, refused MI5’s requests for a warrant to monitor his correspondence.

MI5 had been slow to recognise the danger posed by fascism, but by the late-1930s, it saw that Nazi Germany was the main threat to Britain. This report highlights Hitler’s territorial ambitions, and his contempt for British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain and his belief in ‘peace in our time’.

MI5 started the war on the back foot. Newly relocated to Wormwood Scrubs prison, where working conditions were poor and morale low, it was under-resourced and quickly overwhelmed. Kell was blamed and forced to step down.

Confidence was restored with the appointment of Sir David Petrie as Director General in April 1941. In 1940, Nazi Germany launched an espionage campaign in Britain ahead of a planned invasion.

German spies arrived by boat, submarine and parachute. Many were poorly trained and some spoke no English. Nearly all of them were detected and many were interrogated at Camp 020 on Ham Common in Richmond-upon-Thames.

Josef Jakobs was arrested after breaking his ankle when he parachuted into Huntingdonshire. He was interrogated at Camp 020 but proved uncooperative. Tried under the 1940 Treachery Act, he became the last person to be executed in the Tower of London.

Not all German agents proved so loyal. Many agreed to be turned by their MI5 handlers into double agents, sending back false information to their former masters in Berlin.

One such was Wulf Schmidt. Codenamed TATE after his recruitment by MI5, the false intelligence that Schmidt relayed was so convincing that the Germans awarded him the Iron Cross. Schmidt was part of a network of over 120 double agents.

Known as ‘Double Cross’, this system was one of MI5’s most dazzling successes. As part of Operation Fortitude, they helped convince the Germans that the main Allied landings in 1944 would happen along other areas of the European coast, including the Pas-de-Calais, rather than Normandy.

Perhaps the greatest double agent of them all was a Spanish farmer and passionate anti-Nazi, Juan Pujol Garcia. Recruited by MI5, and codenamed GARBO, he co-created an entirely fictional network of 27 sub-agents which enabled him to flood the Germans with misleading information.

Even after the Normandy landings had taken place, GARBO maintained that they were a sideshow, and the true Allied invasion was yet to come, in the Pas-de-Calais. The Germans took the bait. Throughout July and August, they maintained two armoured and 19 infantry divisions in the Pas-de-Calais and consequently, the Normandy bridgehead was kept safe.

By diverting German resources away from the real D-Day invasion force, MI5, especially the men and women of Double Cross, contributed to the success of the Normandy landings and so played a key role in the eventual Allied victory.

No sooner did one war stop, than another began. Even before the surrender of Germany in 1945, the Soviet Union had been identified as a growing threat to British interests. The Cold War that followed, with the USA and its western allies on one side, and the Soviet Union on the other, was to last for 46 years.

Detonation of the atomic bombs over Hiroshima and Nagasaki had helped bring the Second World War to an end. The world-changing power of this new weapon meant that the Soviets were desperate to know more. It was partly MI5’s job to identify anyone leaking atomic secrets.

Scientist Klaus Fuchs fled Nazi Germany for Britain before being sent to the US in 1943 to work on the atomic bomb. Despite being vetted three times by MI5, he had actually been a Soviet spy since 1941. He passed the Soviets a huge amount of detailed information, including the plans for the first atomic bomb.

MI5 first put Fuchs under surveillance in 1946 and 1947, and this was renewed in 1949. A listening device was placed in his home at Harwell, the Atomic Energy Research Establishment. Under the expert interrogation of former Special Branch officer William Skardon, Fuchs eventually confessed, but he never named his contacts. He was sentenced to 14 years in prison, the maximum term for espionage.

MI5 went on to adopt a far more intensive vetting process. Soviet attempts to penetrate the military continued. In the early 1960s, the government of Harold Macmillan was plagued by a series of spy scandals.

The Portland Spy Ring was one of the most notorious. Two British employees at the Admiralty Underwater Weapons Establishment, Harry Houghton and Ethel Gee, also known as ‘Bunty’, were passing secrets to the Soviets. Here they are during a trip to meet their KGB handler, Konon Molody, who was operating under the false identity of a Canadian vending machine salesman called Gordon Lonsdale.

A Polish double agent informed the CIA of the conspiracy, and they alerted MI5 who mounted a surveillance operation against Houghton and Gee. Here, amid domestic chatter about tinned pears, they were heard talking about getting access to documents.

MI5 followed the documents from Molody, who passed photographic copies of them to Morris and Lona Cohen, American-born KGB agents posing as respectable antiquarian booksellers Peter and Helen Kroger. The Krogers used their bookselling business as cover to send the information to Moscow.

When MI5 searched the Krogers’ rented bungalow in suburban Ruislip, they found it was full of espionage equipment. This tin of talcum powder found in Lonsdale’s flat has hidden compartments in which a microdot reader and pieces of film were concealed. Microdots contain text and images reduced to the size of a full stop.

The Krogers’ radio equipment was state of the art. It could send messages to the Soviets at extremely high speeds.

MI5 were also confronted by threats from within, most notably the Cambridge Spies. Harold ‘Kim’ Philby, Guy Burgess, Donald Maclean, Anthony Blunt and John Cairncross formed the most infamous spy ring of the 20th century. All graduates of Cambridge University, they were recruited by Soviet intelligence during the 1930s.

By the early 1950s, they had penetrated all the major institutions of British state security. Donald Maclean, passed many vital secrets to the Soviets during his career as diplomat. But he found the strain of living a double life increasingly difficult to cope with. In 1951, thanks to the efforts of Philby and Burgess, he was tipped off that US codebreakers had found evidence of his treachery.

Burgess had supplied his Russian handlers with secrets gleaned from his work at the BBC, MI6 and the Foreign Office. His passport contains many diplomatic visas for the journeys he undertook in these roles.

This surveillance report contains the last sighting MI5 had of Maclean, and the observations made of a recent meeting between him and Burgess. The observation that there was ‘an air almost of conspiracy between the two’ is something of an understatement. The two men took the ferry to St Malo together, travelling through Switzerland and Prague to Moscow where they defected.

As well as many unpaid debts, Burgess left behind him two cases at the Reform Club in London. MI5 collected this dispatch case. The other, a briefcase, was taken by Anthony Blunt, who later handed it to MI5 minus any potentially incriminating items.

Blunt, who had worked for MI5 from 1940-45, was not then under suspicion. A distinguished art historian and Surveyor of the King’s Pictures, he had passed top secret military intelligence to the Soviets during the war. Blunt had made a sweep of Burgess’s flat when the diplomat disappeared, but left behind documents that incriminated Cairncross.

Thirteen years later, Blunt was living in this flat, above the Courtauld Institute of Art, of which he was the Director. Here he was visited by MI5 officer Arthur Martin. In return for immunity from prosecution, Blunt confessed to having been a spy for the Soviet Union, though he was never fully open about his role.

When the Queen was told about him in 1973, not long after he had stepped down from his position as Surveyor of the Queen’s Pictures, she reacted ‘very calmly and without surprise.’

For many years, little was known about the fifth man of the Cambridge Spy Ring, John Cairncross. Arthur Martin had also interviewed him, shortly before speaking to Blunt. Cairncross was then living in the US and teaching at a university in Cleveland, Ohio. He had previously worked at the Foreign Office, the Treasury, the Government Code and Cypher School at Bletchley Park and MI6, and had passed many highly classified documents to Moscow after being recruited by Soviet intelligence back in 1936.

As this telegram from Washington informs MI5, Cairncross confessed to spying from 1936-1951. He declined to repeat the confession under caution in Britain.

But the most ruthless and successful of all the Cambridge spies was this man, Harold ‘Kim’ Philby. His work with MI6 during the war gave him access to many high-level secrets. By passing them to his Soviet handlers, Philby cost scores of people their lives.

In August 1945, Konstantin Volkov, a Soviet intelligence officer, contacted the British vice consul in Istanbul. In return for money and political asylum in the west, he promised to deliver valuable intelligence including details of Soviet agents in Britain. Word got back to Philby, and he informed his Soviet contact immediately. Volkov and his wife Zoya were drugged, taken to Moscow, interrogated and executed.

Four years later, in 1949, Philby was MI6 Station Chief in Washington DC, a prestigious post in British Intelligence. But the defection of his friends Burgess and Maclean in 1951 brought him under ‘grave suspicion’ and he lost his job.

As Director General White’s memorandum demonstrates, the authorities could do no more about Philby, whom they now codenamed PEACH. They had no evidence. It wasn’t until 1962 that Flora Solomon, who had known Philby since the 1930s, revealed that he had tried to recruit her as a Soviet agent before the war.

This, at last, was proof, and in January 1963, one of Philby’s MI6 colleagues, was sent to Beirut, where Philby was working as a journalist and an MI6 agent. During one of their meetings, Philby handed the MI6 officer a typed confession, though the account of his treachery was incomplete, only covering the years from 1932-1940.

In the transcripts of their conversations, Philby claimed to have spied for the Soviet Union from 1934-1946 but he gave no meaningful explanation of why he allegedly stopped. It amounted to disclosure of a sort, but on Philby’s terms.

Philby fled to the Soviet Union on 23rd January. Neither Philby, nor any of the other Cambridge spies, were ever prosecuted.

The revelations about the Cambridge Spies led to an atmosphere of paranoia in the 1960s and 70s. Even the Prime Minister himself, Harold Wilson, accused MI5 of conspiring against him.

In 1986, the British government attempted to block the publication of ‘Spycatcher’, a memoir by former MI5 Scientific Adviser, Peter Wright. It repeated Wilson’s allegations about a plot against him. Former KGB employee Oleg Gordievsky debunked one of Wright’s key claims, that former MI5 Director General Sir Roger Hollis had been a Soviet spy.

As the Cold War came to an end, MI5’s focus changed. From being a largely counter-espionage organisation, it now had to adapt to confront a rising threat: terrorism.

The Provisional Irish Republican Army bombed civilian, military and political targets in mainland Britain from 1972-1997. In February 1991, the Provisional IRA launched three mortar bombs at 10 Downing Street.

MI5’s C branch had recently advised that the windows there should be replaced with reinforced laminated glass. A C branch insider later remarked, ‘had it not been for the windows, the place would have been shredded’.

One of the worst terrorist attacks ever to take place in the UK occurred on 21st December 1988. A PanAm Boeing 747, bound for New York, was brought down over the Scottish town of Lockerbie. All 259 passengers, and 11 people on the ground, were killed.

A search of the wreckage by MI5, the FBI and the Scottish police, identified a suitcase which had contained an improvised explosive device, or IED. MI5’s IED expert identified the circuit board used in the device, which eventually led investigators to Abdelbaset al-Megrahi, the Libyan intelligence officer found guilty of murder for the bombing.

After the 9/11 attacks in the US in 2001, Islamist terrorism became the most significant threat to the UK. Today, it makes up about 75% of MI5’s work.

Between 2017 and 2024, MI5 and the police disrupted 43 late-stage attack plots. In addition, certain states have in recent years conducted sabotage, espionage, cyber attacks and assassination attempts against the United Kingdom.

As MI5 Director General Ken McCallum has put it, ‘These threats mean we now live in the most complex threat environment the UK has ever faced.’ But during its long history, MI5 has proved itself able to develop and adapt in the face of a multitude of threats and challenges.

In a dangerous and uncertain world, MI5 will continue to use all its resources and ingenuity to keep the country safe.

This video can also be viewed on YouTube with optional closed captions. Watch "MI5: Official Secrets Exhibition video tour" on YouTube.

The National Archives is the official archive of the UK government, and England and Wales. We are the guardians of over 1,000 years of iconic national documents.

Everyone is welcome to visit our headquarters in Kew. We put on exhibitions, events and displays and offer reading rooms giving access to our collections there.

The National Archives is located by the River Thames in Kew, 30 minutes from Central London. We offer advice on travelling to us by car, bike, train or bus.

Monday: CLOSED

Tuesday: 10:00–19:00

Wednesday: 10:00–17:00

Thursday: 10:00–19:00

Friday: 10:00–17:00

Saturday: 10:00–17:00

Sunday: 11:00–16:00

Last entry to this exhibition is one hour before it closes each day.

We recommend checking our full opening times and bank holiday closure dates when planning your visit.

Groups of ten people or more must book in advance, at least seven days before your visit.

We unfortunately cannot accept group bookings in the first and last two weeks the exhibition run.

Find out more about booking group visits and our exclusive entry packages for groups.

Everyone is welcome to visit this exhibition.

We provide a warm welcome to visitors of all ages, including children and family groups.

We have a café and coffee bar provided by Maids of Honour, a historic local tea room and bakery. It has spacious indoor and outside seating and a soft play area.

On the menu is a variety of high-quality lunchtime meals, sandwiches, snacks, soft drinks, tea and coffee. Vegetarians, vegans and other dietary requirements are all catered to.

Keen to explore espionage right now? Read articles on the exhibition’s themes.

The story of

When can a lemon have fatal consequences? If it proves you are, in fact, a wartime spy…

Focus on

The book Spycatcher sparked one of the most controversial courtroom battles of the 1980s, bringing questions around state secrecy to a global audience.

The story of

A life of charm, high-stakes, and duplicity saw Elvira Chaudoir play a cunning role in the Allied victory at D-Day.

The collection

Inspired to discover tales of espionage and intrigue? Find out how to start researching the records of MI5 and British intelligence services we hold.

Focus on

In 1938, thanks to years of work by a remarkable female agent, MI5 ensured a package of British defence plans stayed secret.

The story of

Security Service files paint a vivid picture of what happened when Anthony Blunt – then employed in the royal household – admitted spying for the Soviet Union.

The story of

Virginia Hall (1906–1982) was an American who served with the British Special Operations Executive in France in 1941–1942 and built a career in espionage.

Browse the very best books about spy history and more...