Important information

This page includes a quote with archaic description of poor mental health.

Early life and career

Born on 11 March 1810, Henry was baptised the following day as a Roman Catholic in St Mary’s Pro-Cathedral, Dublin. His parents, William and Jane, were affluent brewers and bakers who owned Raheny House in County Dublin. In 1829 Henry entered Trinity College, partly due to the passing of the Roman Catholic Relief Act that same year. This act removed many civil restrictions on Roman Catholic citizens, including the right to enter higher education. At Trinity College, Henry obtained a bachelor's degree and later studied to become a barrister, an unusual but not completely uncommon profession for a Catholic in post-Union Ireland. In 1837 he was admitted to the bar at the King’s Inns, Dublin.

By 1841 Henry had left Ireland, though it is not known why.

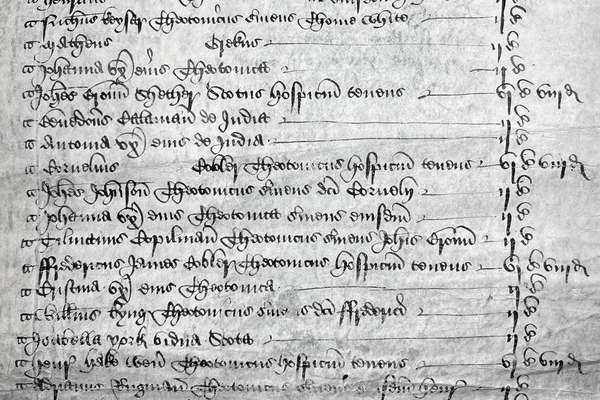

The England and Wales census records him lodging on Manchester Square in Marylebone, London. This census describes him as ‘aged thirty’ and of ‘independent means’.

Entry for Henry Sweetman, 6 Manchester Square, Marylebone, England and Wales Census 1841 (Catalogue reference: HO 107/680/11)

Henry was clearly fond of Marylebone as, in the 1851 census, he was recorded as lodging there again, though he had relocated to 11 Bentinck Street, a five-minute walk away from his previous boarding house. This census records that Henry, now forty-one, was a ‘barrister not practicing’, so it is likely he had a sizeable private income, probably from lands the family held in counties Dublin and Armagh.

Historical scholarship

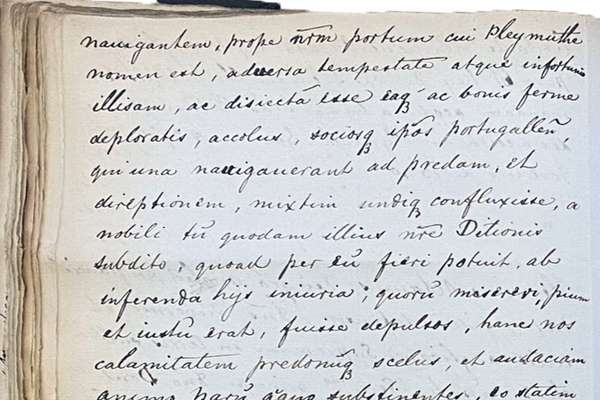

During the 1850s, we begin to see Henry’s engagement in the antiquarian scholarship, which resulted in his Calendar of documents relating to Ireland in Her Majesty’s Public Record Office, 1171–1307.

From later correspondence, we know that in 1864 he submitted a proposal for a project to calendar, essentially summarised translations, documents relating to Ireland in the newly opened Public Record Office on Chancery Lane. Yet, it appears that the Deputy Keeper, Thomas Duffus Hardy, and his staff showed little enthusiasm as Henry worked hard to show the value of his project and his suitability to undertake it in the following years.

Making progress

In 1868, Henry compiled a collection of extracts of deeds and writings found on the King's Remembrancer memoranda rolls (Catalogue series E 159) for the reign of Edward I (1272–1307). This demonstrated he could engage with documents and had good historical deciphering skills. In the same year, on 14 December, he gave a lecture to the Royal Irish Academy on records relating to Ireland housed in England.

H. S. Sweetman (ed.), Remarks on The Early English Public Records relating to Ireland (Chiswick Press, 2 June 1870). (Catalogue reference: LRRO 11/5)

This presumably provided the foundation for the pamphlet he published in London on 2 June 1870, entitled ‘Remarks on the early English public records relating to Ireland’, which highlighted the need for the project.

Henry’s plan

By the time Henry’s pamphlet came out, he had returned to London, living at 4 Dorset Street, Manchester Square.

Here, on 6 April 1872, Henry wrote to Hardy to stress his eagerness to revive his Calendar ambitions.

Henry’s letter reveals the full scope of his proposal: he would calendar documents relating to Ireland in the Public Record Office from the reign of King Henry II (1154–1189) or King John (1199–1216) up until the reign of Queen Victoria (1837–1901).

In subsequent supportive letters sent by Hardy to government officials, the timeline was pared back to end with the reign of Henry VII (1485–1509), to compliment an ongoing project to calendar the Tudor State Papers, led by Hardy and John Sherren Brewer. Accordingly, Henry was finally able to undertake this work, now that its scope suited the State.

Henry was officially commissioned late in 1872 to compile a calendar of documents from the reigns of Henry II to Henry VII (1154–1509). He was to be paid £200 annually from 1 April 1873 and at £5 per sheet, each volume containing 40 sheets (or 640 pages).

Henry’s response affirmed that he would have ‘much pleasure in undertaking the calendar in question’.

Letter signed by H[enry] S[avage] Sweetman to Thomas Duffus Hardy, Deputy Keeper of Public Records, noting his hope that his Calendar ‘would prove of great and lasting public utility both in Ireland and elsewhere’. London, 4 April 1872 [Ref. PRO 1/37]

Letter of Henry Savage Sweetman to Thomas Duffus Hardy, Deputy Keeper of Public Records, advocating for his Calendar of records relating to Ireland in the Public Record Office, London, 6 April 1872. [Catalogue reference: PRO 1/37]

Calendar of Documents Relating to Ireland in Her Majesty’s Public Record Office, 1171–1307, ed. H. S. Sweetman with G. F. Hadcock, 5 volumes (Dublin, 1875-86)]

The first volume (covering 1171–1251) appeared in 1875. Thanks to a letter sent on 9 October of that year by the Deputy Keeper to the Under-Secretary of State at the Home Office, Adolphus Liddell, we know where official copies were sent, including to Queen Victoria’s library, the library of the India Office, the Royal Irish Academy in Dublin (of which Henry was now an elected member), the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, and Chetham’s Library in Manchester.

Triumph

At the time of the first volume’s publication, Henry was living at 8 Abbey Gardens, Abbey Road, London, five doors down from where Abbey Road Studios of Beatles fame were later located.

He subsequently moved to 38 Alexandra Road, about a ten-minute walk away, where he lived from 1877 until 1881 as a boarder with the historical author Sutherland Menzies.

Entry for Henry Sweetman, 38 Alexandra Road, St John’s Wood, England and Wales Census 1881 (Catalogue reference: RG 11/173/69)

Throughout the following years Henry worked with determination: the second volume (1252–1284) appeared in 1877, the third (1285–1292) in 1879, and the fourth (1293–1301) in 1881. The Calendar includes accounts, letters sent to, from, and about Ireland, as well as records of court cases in England which concerned Ireland.

The importance of these documents is enhanced by the fact that the majority of records produced by the English government in Ireland were lost during medieval and modern conflicts. This was most catastrophically the case in 1922, during the Irish Civil War, when Ireland’s Public Record Office was destroyed and with it the rich remnants of the country’s medieval past.

Importantly, the Calendar identifies and provides easy access to some of the earliest records of nearly eight centuries of English/British lordship over Ireland. You can find digital versions of the Calendar with searchable metadata and other reconstructed series of ‘lost’ medieval (and later records) on the Virtual Record Treasury of Ireland website.

Later tragedy

Little is known of Henry’s later activities until 9 February 1884. Here, we find a letter by his nephew, John Andrew Sweetman, which was sent to the Master of Rolls, William Baliol Brett, 1st Viscount Esher. According to his nephew, in September 1883 Henry, whom he described as ‘of the Record Office’, was knocked down by a black cab in London, causing concussion of the brain which resulted in ‘absolute and hopeless lunacy’.

John sought financial support for his uncle from the British government, for which he secured the support of the Deputy Keeper, William Hardy. It is not clear whether Henry returned to Ireland after the accident, though we know from his death certificate that he died in Brooke House Asylum, Hackney, on 5 August 1884 of 'Cerebral Anaemia', where the brain is deprived of sufficient oxygen and may ultimately lead to a stroke. Brooke House was a private institution, suggesting that Henry had a patron or relative able to afford the fees.

Henry’s legacy

By pulling together several strands we can uncover the rich life of Henry Savage Sweetman and how his calendar of documents fits into it.

Unfortunately, much remains unknown. Questions such as what inspired the project, and whether he was influenced by the contemporary debates around Home Rule in Ireland, may go unanswered. Yet we do know that Henry himself was an inspiration. His work on Ireland stimulated a similar project calendaring documents relating to Scotland in the Public Record Office.

In the preface to the first volume of his calendar, its editor Joseph Bain paid homage to Sweetman, ‘whose valuable Calendar has been the model on which the present one has been drawn up, he has been often indebted for counsel’.

In addition to inspiring his contemporaries through this monumental work, compiled before the wonders of technology transformed archival access and analysis, Henry has galvanised countless subsequent historians, affirming the importance of English records for understanding medieval Ireland.

This article was written in collaboration with Dr John Marshall of Trinity College Dublin.

Read more

Calendar of documents relating to Scotland, preserved in Her Majesty's Public Record Office, London: Volume 1, 1108–1272, ed. Joseph Bain (Edinburgh, 1881).

More on Irish history

Record revealed

A medieval Irish roll with hidden grievances

This roll provides a glimpse into how medieval Ireland was governed, but today plays a starring role in the development of scientific methodologies.

Record revealed

Letter patent with the Great Seal of Ireland attached

This unexpected gem is a document granting land in Ireland to a John Farrell. Attached is the Great Seal of Ireland, indicating approval from King Charles II.