The rise and decline of the first global empire.

This resource has been archived as the interactive parts no longer work. You can still use the rest of it for information, tasks or research. Please note that it has not been updated since its creation in 2003.

You can find more content on this topic in our other resources:

Lessons

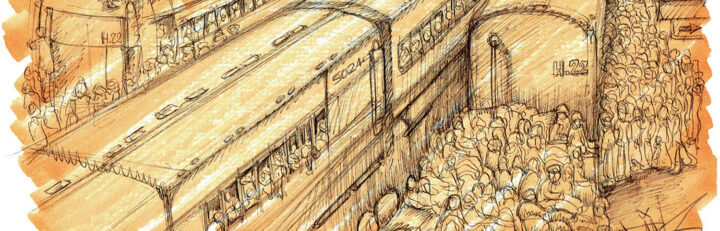

- Partition of British India

What can The National Archives documents reveal about the partition of British India? - The Search for ‘Terra Australis’

What did Captain Cook’s secret mission involve? - Irish Partition

Why was Ireland divided in 1921? - Native North Americans

What was early contact like between English colonists and Native Americans?

Themed collections

- Indian Independence

What led to Partition in 1947? - Loyalty and dissent

How did Indian soldiers respond to the First World War?