Record revealed

The Monteagle Letter

Is this the most famous anonymous letter in British history? Perhaps it should be. Without it, the Gunpowder Plot might have succeeded.

Past exhibition

Treason: People, Power & Plot was a major exhibition from The National Archives on the history of treason since 1352.

It is now permanently closed. The exhibition brought iconic and unknown archival documents to life, including the original Treason Act and the Monteagle Letter that tipped off the Gunpowder Plot.

From the most famous treason trials such as Guy Fawkes, Anne Boleyn and Charles I, to the cook who poisoned the porridge and the young girl tried as a witch, the exhibition showcased nearly 700 years of treasonous history.

Get a glimpse of what visitors to the exhibition could see and do while it was open.

Image 1 of 3

Examine the trial record of Queen of England Anne Boleyn, who in 1536 was tried for treason, adultery and incest with her brother. Catalogue reference: KB 8/9

Image 2 of 3

See the Tudor Bag of Secrets in which the trial records of Edward, Earl of Warwick, were stored. Catalogue reference: KB 8/2

Image 3 of 3

Read the declaration signed by Guy Fawkes, dated 17 November 1605, in which he named his co-conspirators in the Gunpowder Plot. Catalogue reference: SP 14/216

Watch

Treason: People, Power and Plot exhibition tour

on YouTube

Watch

Treason: People, Power and Plot exhibition tour

on YouTube

Treason.

Dry words on dry parchment have tried to capture my essence.

But those spidery words are mercurial.

Subject to whims of kings and queens.

Of lords and ministers and all those who fear that their power may be challenged.

They are right to fear.

All power is always challenged.

Traitors are only traitors when their plots fail.

The monarch clings to their throne.

The rivals plot to take it.

And once taken…

The work begins again to choke seditious thought at its root.

And the root is always an idea.

And it is always nourished.

By thought and hope and fear and anger and… dreams.

I have always been a thought…

An act of imagination…

Used by those in power to define who is a traitor… and who is not.

Treason is revenge.

Violence.

Murder.

Rebellion.

Execution.

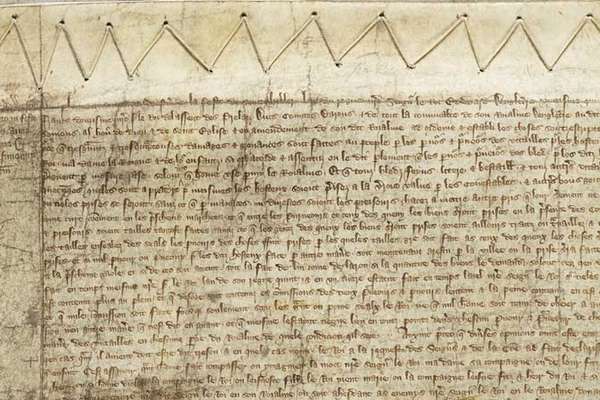

The concept of treason is as old as English law.

In Alfred the Great’s legal code, it is described as the worst crime an individual could commit – an act on a par with Judas’s betrayal of Christ.

Until the mid-1300s, however, the definition of treason was dangerously flexible.

Arbitrary accusations of treason were used to crush rebellions and shatter rival factions competing for power at court.

It was only with this document, the Treason Act of 1352 that a clear definition was established.

The early 1300s were a time of great instability.

During his tumultuous reign, King Edward II had often levelled arbitrary charges of treason against his subjects.

In the end, he was deposed, imprisoned and probably murdered so when his son, Edward III, succeeded him, the new King needed to reset the relationship between the Crown and nobility.

The Treason Act was key to this.

It protected the King and his bloodline but it also answered Parliament’s request for a legal definition of treason.

Never more could the King accuse his subjects of treason on a whim.

Instead, he would have to prove that they were guilty of any of the following:

Plotting the death of the King, his queen or their eldest son or “compassing and imagining the same”; Violating the queen, the King’s eldest daughter out of wedlock, or his eldest son’s wife; Levying war against the King or aiding his enemies; Counterfeiting the King’s seals or money; Or killing the king’s officials, the chancellor, treasurer and certain royal justices while performing their royal duties.

The Treason Act passed into law when Edward III was at the peak of his power, with a string of victories in the French wars behind him.

But it made provision for the future expansion of the definition of treason, to be decided by the King in Parliament.

From then on, Parliament could help to define what constituted treason.

Whenever power ebbed from the Crown, those who controlled Parliament could use that to their advantage.

For the next two hundred years the concept of treason was continually reshaped by rival noble dynasties, power-hungry claimants to the throne, and violent civil war.

Treason was not always a matter of actively conspiring against the monarch.

Here, Eleanor Cobham, Duchess of Gloucester, is accused of encouraging three priests to invoke demons and spirits to predict when King Henry VI would die.

That alone was a treasonous act.

What made it worse was that Eleanor was married to the King’s uncle, the man who would succeed him if he died.

She denied all the charges but her marriage, now seen to be tainted with sorcery, was annulled and she was sentenced to life imprisonment.

From the mid-1400s, there was a new way to comprehensively punish those accused of treason: Parliamentary Attainder.

A declaration was made in Parliament that an individual or group had committed treason.

Those accused were not present to contest the allegations but if Parliament found against them, they became “attainted”: their bloodline was held to be corrupted and their lands, possessions and titles were forfeited to the Crown.

We can see a particularly outrageous example here, in the posthumous attainder of Richard III, who was defeated by Henry Tudor at the battle of Bosworth in 1485.

Richard is accused of numerous crimes and misdeeds, including “unnatural, wicked and great perjuries, treasons, homicides and murders”.

This list of wickedness culminates in high treason against “our said sovereign lord”, Henry Tudor, King Henry VII.

Of course, Henry wasn’t the “sovereign lord” until after Richard’s death.

To make the attainder work, he’d backdated the beginning of his reign to the day before the battle.

Henry VIII’s reign brought with it many new interpretations and punishments for treason, the sure sign of a power-hungry king keen to maintain obedience among his subjects.

His most controversial move is detailed in this, the 1534 Act of Supremacy.

Here, Henry VIII broke from the Catholic Church and declared himself

“Supreme Head of the Church of England”.

Despite many people’s enduring spiritual allegiance to the Pope, it became treason to deny Henry’s supremacy.

The full implications of this rupture would not be felt until after Henry’s death, when the faith of the nation shifted from Protestant to Catholic and back again, cultivating fertile soil for treason to flourish in.

During Henry’s reign, the 1534 Treason Act was passed to punish anyone who said that the King was a heretic and an infidel for titling himself “Supreme Head of the Church of England”.

One of its earliest victims was Sir Thomas More, the former Lord Chancellor who was a staunch opponent of the Protestant Reformation.

More was arrested after he refused to swear the Oath of Succession.

He did not deny the Protestant Anne Boleyn’s position as Queen or the right of her children to succeed to the English throne.

But the oath’s preamble rejected the authority of the Pope, and More would not agree to that.

He explained his divided loyalties at his trial: The law and statute whereby the King is made Supreme Head, be like a sword with two edges.

For if a man say, that the same laws be good, there is danger to the soul; and if he say contrary to the said statute, then it is death to the body.

More was beheaded on Tower Hill in July 1535.

The Gunpowder Treason – the most famous attempted treason in British history was foiled in the early hours of the 5th November 1605.

It was much larger in scope than any conspiracy attempted before or since, targeting not only King James, but his closest family, his councillors, senior officers of the realm, and members of parliament.

This was an unprecedented treason against both the monarch and the state.

The plot was discovered as the result of this letter to Lord Monteagle, a prominent Catholic.

It warns him not to attend the opening of Parliament.

Monteagle immediately informed the King and his council.

The cellars under Parliament were searched and, in a vault beneath the House of Lords, 36 barrels of gunpowder were found.

The vault’s keeper – Guy Fawkes – was immediately arrested for questioning.

The hunt was on for Fawkes’s co-conspirators and Thomas Percy, who had leased the vault under Parliament, was top of the list.

Copies of this proclamation were distributed across the country.

When first arrested, Fawkes had given his name as John Johnson.

During November, his real name and those of his fellow conspirators were tortured out of him.

This was first propounded unto me about Easter last by Thomas Wynter and there were imparted our purpose to three other gentlemen more namely Robert Catesby, Thomas Percy, and John Wright, who all five consulting together of the means how to execute the same.

Catesby propounded to have it performed by Gunpowder.

Fawkes’s contorted signature on this confession is mute witness to the agonies he must have suffered.

Fawkes was tried with six of his co-conspirators in January 1606.

So serious was their crime that the records of the trial were removed from the main King’s Bench record series and placed in this leather bag known as the “baga de secretis”, the “bag of secrets”, and locked away.

Since 1352, treason laws had protected the life and authority of the monarch.

But did these same laws equally protect the state and its people?

The gunpowder plotters in 1605 had acknowledged that, to achieve their aims, they needed to remove not just the head – King James I – but the entire body – Parliament.

And if treason laws protected the state as well as the king, who did they protect when the king and his kingdom were at odds?

This question would be definitively answered during the reign of James’s son, Charles I.

Charles I couldn’t bring himself to acknowledge Parliament’s sovereignty within the realm.

He jealously guarded his authority, bitterly resisting what he saw as Parliament’s attempts to encroach upon it.

By 1642, relations between the two had broken down completely, leading to years of bloody civil war.

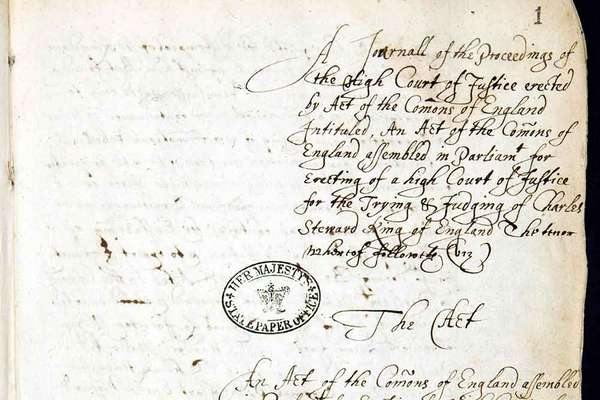

But after Parliament’s victory over the King in 1648, it was decided to make Charles pay for his crimes against the state.

For the first time, a king was tried for treason against “the Parliament and the Kingdom of England”.

Charles refused to accept the authority of the High Court of Justice that had been specially convened to try him, but to no avail.

On the 27 January 1649, John Bradshaw, Lord President of the Court, passed sentence in these words: “Charles Stuart, as a tyrant, traitor, murderer, and public enemy to the good people of this nation, shall be put to death by the severing of his head from his body.”

Three days later, the King was executed, and a republic was proclaimed, lasting until 1660.

After the death of Oliver Cromwell in 1658 and the subsequent collapse of the English Commonwealth, Charles II was recalled from exile and restored as monarch in 1660.

While determined to avenge his father's death, Charles II made it clear that he had no desire to reignite the civil wars.

Instead, he declared his wish to heal the divided nation “with as little Blood and Damage to our people as is possible”.

But he was intent on pursuing his father’s killers.

Parliament passed several acts that explicitly named those guilty of treason for their involvement in the King’s death, exonerating the rest of the population for any involvement in the civil wars.

Charles II was careful to use Parliament and the courts to pursue only those “Persons actively instrumental in the Murder of His late Majesty” – in other words, the men who had passed sentence on Charles I on 27 January 1649.

Some of those men had died in the intervening years but that wasn’t enough to get them off the hook.

This is the order from the House of Commons for the bodies of Oliver Cromwell, John Bradshaw, Henry Ireton, and Thomas Pride to be dug up, ritually executed and their mutilated remains publicly displayed.

For those regicides who had survived, a more agonising fate awaited.

They were traitors to the Crown for their part in the death of King Charles I and trials and public executions followed.

For those who eluded justice, if caught, they too would face the traitor’s death: hanging, drawing, and quartering.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, waves of revolutions and revolutionary ideas swept across the world.

Demands for liberty, equality and political representation collided with the British state and empire as workers, overseas subjects and enslaved and colonised people agitated both peacefully and violently for change.

The charge of treason remained the British state’s supreme weapon, with which it could destroy people and attempt to silence subversive ideas.

In Britain, parliamentary reformers and revolutionaries faced contentious treason charges in jury trials.

Overseas, courts martial used the charge of treason to make short work of those who defied them.

But that did not work everywhere.

For many years, Britain’s 13 American colonies had been left to run their own affairs, in a policy known as “salutary neglect”.

But from the mid-1760s onwards, the British government argued that the colonists should pay for their defence during the Seven Years’ War of 1756 - 1763.

This was the first time taxes of any magnitude had been levied directly from London and the colonists objected fiercely.

In 1773, chests of British East India Company tea were thrown into the sea an act that became known as the Boston Tea Party.

According to the British authorities, this was treasonous.

It constituted levying war against the King and obstructing the execution of a British Act of Parliament.

By August 1775, many people in the American colonies were in open rebellion against King George III.

This proclamation, made by the King, uses the language of treason against them, exhorting loyal subjects in the colonies to “disclose and make known all treasons and traitorous conspiracies”.

But there was no stemming the revolutionary tide.

In Philadelphia, on 4th July 1776, the American Declaration of Independence was made formally rejecting the King’s authority and labelling him a “tyrant”.

One clause describes how “he has plundered our seas, ravaged our coasts, burnt our towns, and destroyed the lives of our people”.

The King may have declared those colonists in rebellion traitors, but to the Americans that signed the Declaration of Independence, George III was the traitor.

Jamaica was Britain’s most important Caribbean colony.

Enslaved people, working in brutal conditions on sugar plantations had generated unimaginable wealth for their oppressors.

But in 1807, the slave trade was abolished in the British Empire, and it became increasingly clear that slavery itself would eventually be outlawed.

By Christmas 1831, the enslaved people of Jamaica could wait no longer.

They rebelled across the northwest of the island, particularly around Montego Bay.

Samuel Sharpe is named the principal leader of the rebellion in this proclamation by the Governor of Jamaica.

Enslaved people were not legally capable of committing treason because in law they were not the King’s subjects.

Instead, they could be executed for “compassing and imagining the death” not just of the King, but of “any white person”.

Sharpe was hanged on 23rd May 1832.

His “owner” marked the “decrease” in his “property” in the slave register.

The court paid him compensation of £6 and 10s, the “value” they calculated for Sharpe’s life.

The Slavery Abolition Act, ending slavery throughout Britain and its empire, was passed the next year.

During the First and Second World Wars, Britain used martial law and emergency powers to try and eliminate any real or imagined treachery.

But in civilian courts, the Treason Act could no longer be relied upon to secure convictions in the highest-stake state trials.

The outbreak of the First World War in 1914 put a stop to the introduction of a bill for Home Rule in Ireland.

This would have offered the administration in Dublin the powers to run its domestic affairs while still being part of the British Empire.

But even this level of independence had been fiercely resisted, especially in Ulster, and many in Ireland thought that the British government would not seek to revive the legislation when war ended.

At Easter, 1916, with Britain distracted by the global conflict, Irish Republicans, under the leadership of Patrick Pearse, seized several key buildings in Dublin, including the General Post Office, and proclaimed a fully independent Irish Republic.

But the rebels were soon overwhelmed by the British Army.

After almost a week of fighting, Pearse surrendered.

Although the Irish law officers argued against the use of courts martial to try the rebels, British authorities didn’t want to give them the public platform of a civil trial.

On 2nd May 1916, Pearse, Tom Clarke and Thomas MacDonagh were tried and found guilty of “taking part in an armed Rebellion and in Waging War against His Majesty the King”.

They were executed by firing squad at dawn the next day.

From prison, Pearse wrote to his mother:

Our hope and belief is that the Government will spare the lives of all our followers,

but we do not expect that they will spare the lives of the leaders. We are ready to die. And we shall die cheerfully and proudly. Personally, I do not hope or even desire to live. You must not grieve for all this. We have preserved Ireland’s honour and our own. Our deeds of last week are the most splendid in the land’s history. People will say hard things for us now, but we shall be remembered for posterity and blessed by unborn generations. You too will be blessed because you are my mother.

In total, 15 men were executed for their part in the Easter Rising.

Far from putting a stop to Irish nationalism, the secrecy of the trials, and the speed with which the executions of Pearse and his allies followed them, turned the tide of public opinion in the rebels’ favour.

British Prime Minister Asquith had ordered that no woman should be executed for her part in the Rising.

So what to do with Constance Markievicz?

She’d been second-in-command to a troop of Irish Citizen Army combatants.

Instead of being found guilty of rebellion, she was convicted of attempting “to cause disaffection among the civilian population of His Majesty”.

Her death sentence was immediately commuted to life imprisonment “solely and only on account of her sex”.

This is William Joyce, the last man to be executed for treason in the UK.

Joyce was a fanatic - a fascist who fled from Britain to Nazi Germany on the eve of the Second World War.

He worked as a radio propagandist, trying to undermine morale.

The drawling upper class accent that he affected in his broadcasts aimed at Britain led to him being nicknamed “Lord Haw-Haw”.

The arguments at his trial focused on his nationality.

Joyce was Irish-American, so how could he be guilty of treason against the British King?

Joyce might have escaped with his life but for a fraudulent British passport.

This is the renewal form he submitted.

The Crown claimed that as he had benefited from the King’s protection, he owed him allegiance, and was therefore a traitor.

Convicted on this technicality, Joyce hanged.

There has been no trial for treason since.

Joyce’s crimes were undeniable, but by framing the case against him in terms of the 1352 Act, it was touch and go whether the state could secure a conviction.

The Act had been revised a number of times in the 600 years since it had been passed, but it was clearly no longer fit for purpose.

In the 76 years that have followed, legislation better suited for our times such as the Official Secrets Acts and the 2000 Terrorism Act – have taken its place.

But the core elements of the Act still remain on the statute book, and the ideas of “treason” and “traitor” stick deep in the national consciousness.

The relationship between the powerful and the rest of us is always in flux.

But, as in all relationships, the one thing that can never be discounted is betrayal.

This video can also be viewed on YouTube with optional closed captions. Watch "Treason: People, Power and Plot exhibition tour" on YouTube.

The National Archives is the official archive of the UK government, and England and Wales. We are the guardians of over 1,000 years of iconic national documents.

Everyone is welcome to visit our headquarters in Kew. We put on exhibitions, events and displays and offer reading rooms giving access to our collections there.

The National Archives is located by the River Thames in Kew, 30 minutes from Central London. We offer advice on travelling to us by car, bike, train or bus.

Love Letters opens on 24 January 2026.

See our opening times.

Everyone is welcome to visit this exhibition.

We provide a warm welcome to visitors of all ages, including children and family groups.

We have a café and coffee bar provided by Maids of Honour, a historic local tea room and bakery. It has spacious indoor and outside seating and a soft play area.

On the menu is a variety of high-quality lunchtime meals, sandwiches, snacks, soft drinks, tea and coffee. Vegetarians, vegans and other dietary requirements are all catered to.

Find out all about a range of treasonous plots – and their consequences...

Record revealed

Is this the most famous anonymous letter in British history? Perhaps it should be. Without it, the Gunpowder Plot might have succeeded.

In pictures

First defined by the 1352 Treason Act, our collections detail centuries of treasonous plots, described in statute rolls, legal records, and state papers

The story of

Through documents held at The National Archives, we can piece together a great deal about the life and reign one of Britain's most infamous medieval monarchs.

Record revealed

The Treason Act defined the crime of ‘high treason’ in law for the first time. It is one of the oldest pieces of legislation still on the statute book today.

Browse our curated collection of Treason-themed gifts.