Extracts from an account of a deputation to the Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin to formally report the results of the Peace Ballot organised by the League of Nations Union, 23rd July, 1935 (PREM 1/178)

An unofficial referendum, the Peace Ballot posed six questions on the theme of disarmament and collective security which were answered by 11 million Britons.

Transcript

…

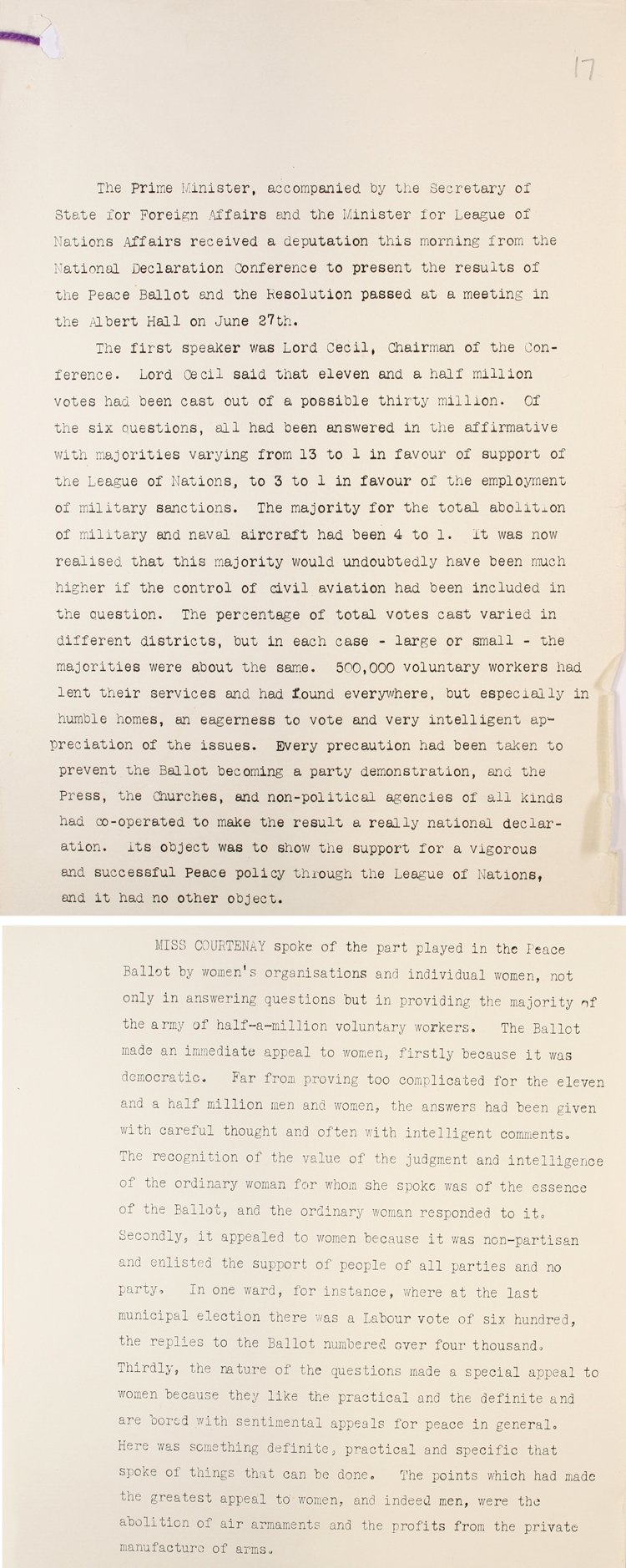

The Prime Minister, accompanied by the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs and the Minister for League of Nations Affairs received a deputation this morning from the National Declaration Conference to present the results of the Peace Ballot and the Resolution passed at a meeting in the Albert Hall on June 27th.

The first speaker was Lord Cecil, Chairman of the Conference. Lord Cecil said that eleven and a half million votes had been cast out of a possible thirty million. Of the six questions, all had been answered in the affirmative with majorities varying from 13 to 1 in favour of support of the League of Nations, to 3 to 1 in favour of the employment of military sanctions. The majority for the total abolition of military and naval aircraft had been 4 to 1. It was now realised that this majority would undoubtedly have been much higher if the control of civil aviation had been included in the question. The percentage of total votes cast varied in different districts, but in each case- large or small- the majorities were about the same. 500,000 voluntary workers had lent their services and had found everywhere, but especially in humble homes, an eagerness to vote and very intelligent appreciation of the issues. Every precaution had been taken to prevent the Ballot becoming a party demonstration, and the Press, the Churches, and non-political agencies of all kinds had co-operated to make the result a really national declaration. Its object was to show the support for a vigorous and successful Peace policy through the League of Nations, and it had no other object.

…

MISS COURTENAY spoke of the part played in the Peace Ballot by women’s organisations and individual women, not only in answering questions but in providing the majority of the army of half-a-million voluntary workers. The Ballot made an immediate appeal to women, firstly because it was democratic. Far from proving too complicated for the eleven and a half million men and women, the answers had been given with careful thought and often with intelligent comments. The recognition of the value of the judgement and intelligence of the ordinary woman for whom she spoke was of the essence of the Ballot, and the ordinary woman responded to it.

Secondly, it appealed to women because it was non-partisan and enlisted the support of people of all parties and no party. In one ward, for instance, where at the last municipal election there was a Labour vote of six hundred, the replies to the Ballot numbered over four thousand. Thirdly, the nature of the questions made a special appeal to women because they like the practical and the definite and are bored with sentimental appeals for peace in general. Here was something definite, practical and specific that spoke of things that can be done. Two points which had made the greatest appeal to women, and indeed men, were the abolition of air armaments and the profits from the private manufacture of arms.

…