British Sign Language Digital Zine

Words by Kate O’Neill, Sound Archivist and Damien Robinson, Artist

Summary of the project

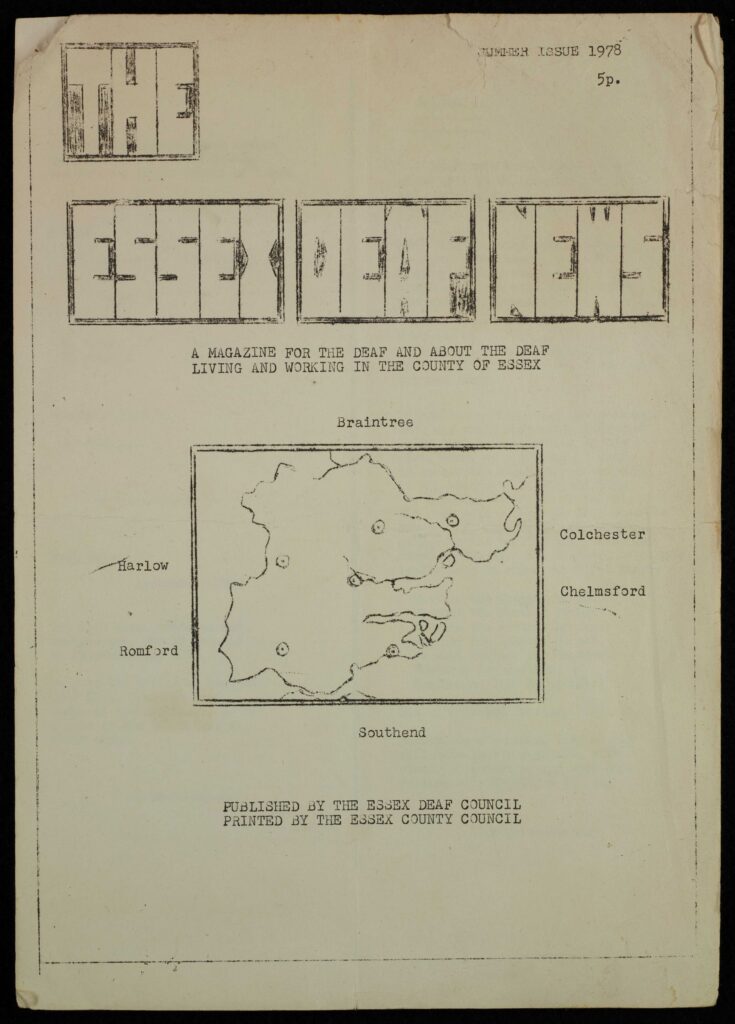

The Essex Record Office (ERO) partnered with Deaf artist Damien Robinson to hold a series of workshops exploring the history of the D/deaf community in Southend-on-Sea. The project, funded by an Engagement Grant from The National Archives, resulted in a digital zine telling the story of Southend’s Deaf history through existing archives, material collected through the workshops, and memories of the participants, filmed in British Sign Language (BSL). The zine is preserved in the Essex Sound and Video Archive.

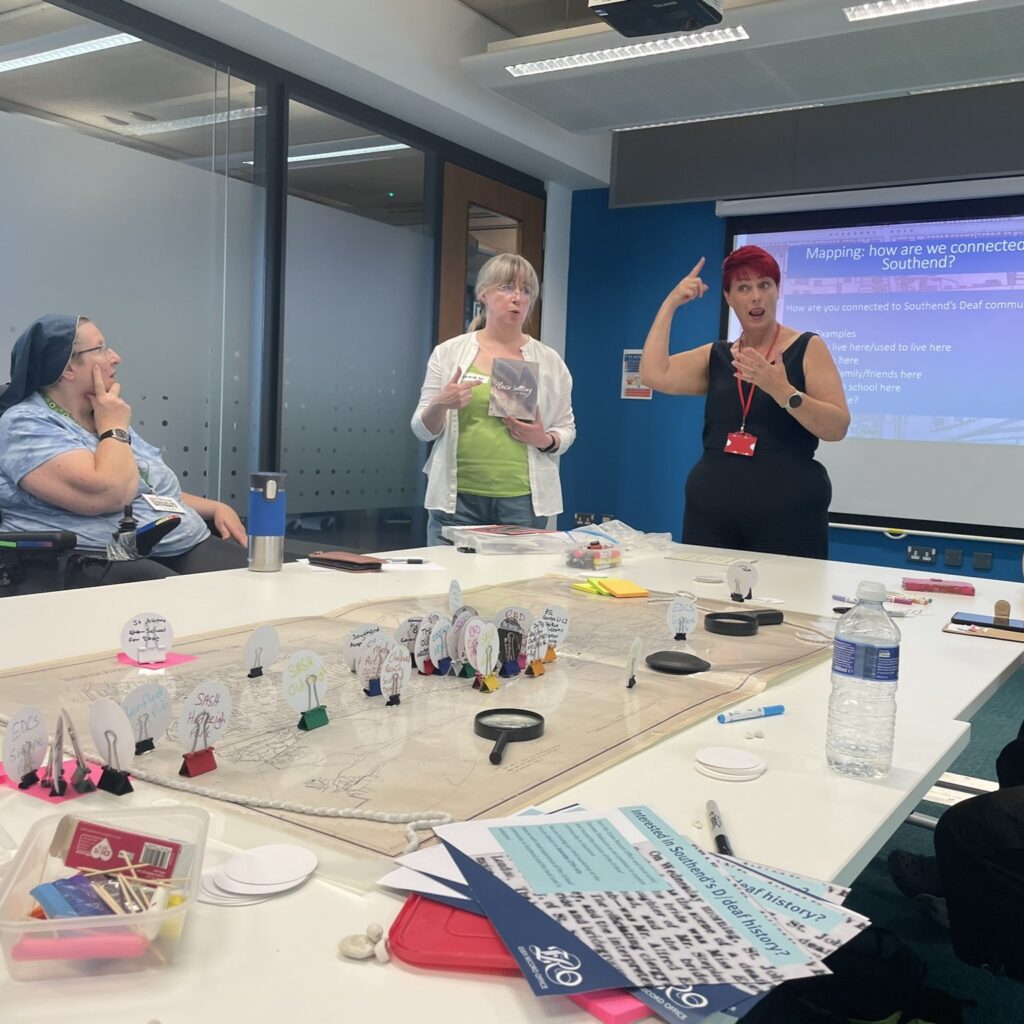

The June workshop on Southend’s Deaf history

Please describe any challenges or opportunities you faced and how you responded to those challenges and opportunities

The project itself was an opportunity to develop Damien’s research into D/deaf history in East Anglia (‘A Kind of Vanishing’). From that project, we knew that there was little recorded in official archives about local Deaf history, and that the D/deaf community in Southend wanted to be involved in changing that.

Having said that, we knew that it might be a challenge to let people know about the workshops and encourage people to come along. We advertised the workshops on social media and online, which was a starting point. But we also printed physical flyers that Damien took to events run by Southend Deaf Pub and the Wickford BSL group. That Damien handed out the flyers and discussed the project (in BSL). This was crucial to raising awareness and building trust. We were also lucky to have the support of Camille Piper, who set up Southend Deaf Pub and helped spread the word about the project. Speaking to people in person had much better outcomes than sharing information online. We also tried to space the workshops out so there was enough time for participation to build organically; after participants came to one session, they generally came back to the next one and told other people about it. It might be obvious to say, but it was also important to make it clear that the workshops themselves were accessible, in terms of the space, structure, and content, with BSL interpreters at each event.

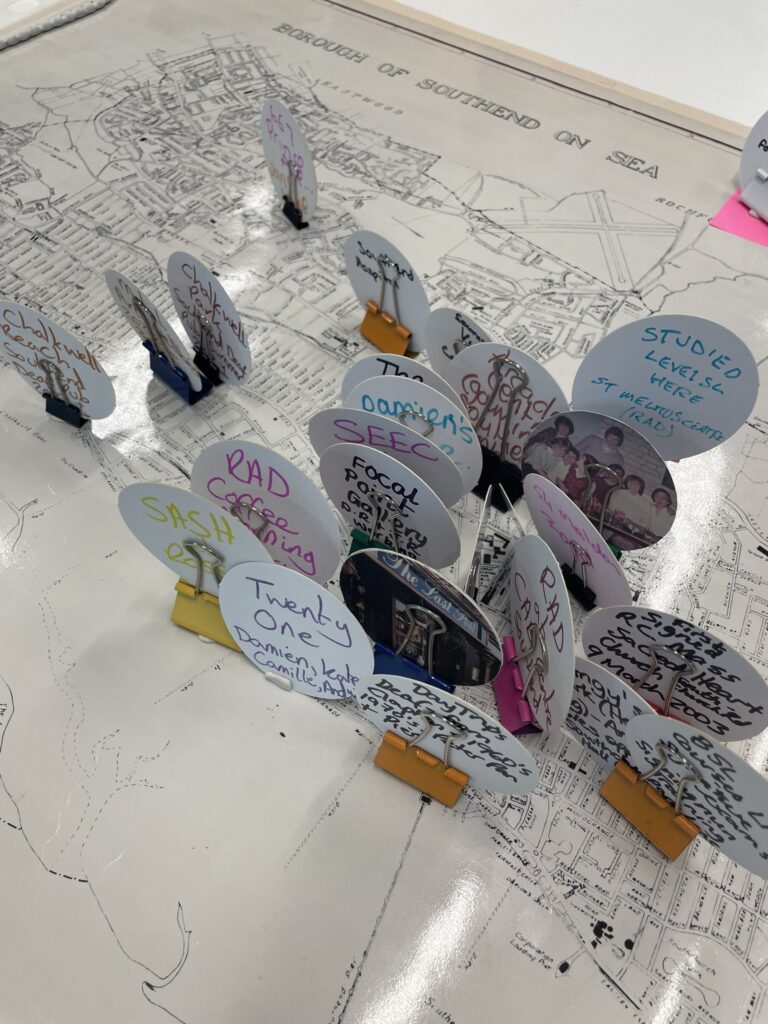

Another challenge was making an output by the end of the project. We wanted to ensure that it included some of our research on existing archival material, responded to what participants wanted and featured their contributions to the project, while being accessible to D/deaf and hearing audiences. In addition, it would need to fit within the project budget! After looking at various other projects (to name just two: Gill Crawshaw’s zine ‘A Handsome Testimonial’ and Nina Crawshaw’s ‘Place Setting’ project) we settled on a digital zine. We are really pleased with the result and hope it will stand as both a legacy for the project and a potential model for future research and engagement around Deaf history in Southend and across Essex.

Markers on the map in the July workshop

What were the outcomes for service users or the parent body?

The feedback we received from people who came along to the workshops suggested that they weren’t just enjoyable to attend, but that they created an important space to discuss, record, and ultimately value Deaf history, and the history of the local community. One participant said that the workshops were “inspiring, liberating, and informative”, while another said that it was “the first project that makes me feel that ‘Deaf Lives Matter’; we can contribute to the world, our lives are just as rich as hearing people, that our legacy and stories are as valuable and interesting too”.

Creating the zine also helped us reach our aim of raising awareness of Deaf history to wider audiences, beyond the workshop participants. Again, we created physical flyers with QR codes, linking to the zine, to hand out at the Royal Association for Deaf people carol service at Chelmsford Cathedral and other Deaf Pub and BSL group events, as well as our stand at Southend City Day. The project has been publicised across Essex County Council networks and in the ‘Explore Essex’ magazine, which can be found at culture and heritage sites across the county.

There were plenty of positive outcomes for the ERO, too. We hadn’t previously worked specifically with D/deaf audiences, so it was an important step forward for us in terms of understanding Deaf culture and history more generally, as well as potential barriers to accessing the ERO for D/deaf people so we could work to address those in future. The project also led to the ERO arranging Deaf Awareness training for members of staff, which spread that learning beyond just me. Damien put together a fantastic document around working with BSL interpreters, for both us and the Forum library in Southend, where we hosted the workshops. The document isn’t publicly available – it was addressed to the library staff doing the tours for us, and some of it is quite specific to that context. But we’ll continue to use it internally and potentially pass it on to partners.

The project also gave us valuable experience in working with an artist and co-creating an output with a specific audience; these lessons will be taken into our engagement project ‘Open the Box’, which is funded by the National Lottery Heritage Fund and aims to open the archives up to a wider audience over the next two years. In the meantime, the project raised awareness of the ERO more generally; although we already had an existing access point in the Forum library, the project renewed the relationship between ourselves and the library staff, leading to the provision of better digital access to the ERO collections.

Essentially the library had been designated as an ‘access point’ since the full branch closed there several years ago, but we weren’t in touch with the library staff very frequently. The ‘access’ provided to ERO collections was really just the provision of microfilm/fiche copies. We got in touch with them to ask for their support before we sent the Engagement Grant application to The National Archives and then spoke quite a bit ahead of the tour they provided, which re-established the relationship. From those conversations we then went on to arrange free access to our digital subscription service on Essex Archives Online, which includes digital images of many of the records that had previously only been accessible on microfilm/fiche. That is now in place and we’re still talking about ways to work more collaboratively.

Essex Deaf News (reference: A16326)

Describe what you learned from the process: What went well? What didn’t go quite as well?

I personally learnt a lot from Damien about Deaf history and culture, and engaging with audiences in a workshop format. Her input into the way the project was structured and run ensured that everything ran smoothly (or meant that we had a back-up option if it didn’t!).

The project also involved a lot of learning on the job. I hadn’t recorded filmed interviews before, not least with an interpreter present, or created captions for films in BSL. Neither Damien or I had created anything like the digital zine before, so ensuring that all the different components worked and that it was accessible after the project ended was another learning curve. Damien’s previous experience and technical knowledge was invaluable in both cases!

Working with a Deaf translator to make the final output accessible was new to both of us but definitely worthwhile. In Damien’s words: “It’s an important area of work and language autonomy for Deaf individuals and the community and I think will grow as time goes on – so it’s good for us to lay down a marker about best practice in a project of this scale.”

If someone was thinking about taking on a similar project, what would be the one piece of advice you would give them?

Be realistic in setting out what you can achieve within the scope of the project and the funding available to you. This can be especially difficult when you’re working with histories or audiences that have been marginalised, when there is still so much to be done. Damien and I had a lot of discussions about this when putting the funding application together. After we were awarded the funding, working in partnership helped us keep that focus and our feet on the ground.

Interview with Camille Piper (reference: SA975)

How will this work be developed in the future?

Over the next few months, we will continue to raise awareness of the digital zine, in Southend and beyond. We would also like to record longer interviews with people who came to the workshops; due to the number of participants, we were limited to 10-minute interviews, which wasn’t enough (as many of them said)! This would give us an opportunity to test out recording full interviews in BSL, which could in turn contribute to ongoing discussions about making ‘oral’ history methodologies more inclusive (see the work of Georgia Anderson, Kirstie Stage, and others) and raising awareness of other life story projects focusing on Deaf history.

In addition to recording interviews, we would like to work with one of the workshop participants to archive her personal collection of material relating to Deaf activism, and in doing so take another look at some of our accessioning procedures – for example, our depositor form – to make them more accessible to future depositors.

In the longer-term future, it was always the intention that the project could be a pilot for future projects exploring Deaf history – potentially in other areas of Essex, or in working with schools (particularly those with Deaf Resource Bases) to create and share resources about Deaf history.