Citizenship is often in the news but what is it? How has it changed over the centuries?

This resource has been archived as the interactive parts no longer work. You can still use the rest of it for information, tasks or research. Please note that it has not been updated since its creation in 2004.

You can find more content on this topic in our other resources:

Themed collections

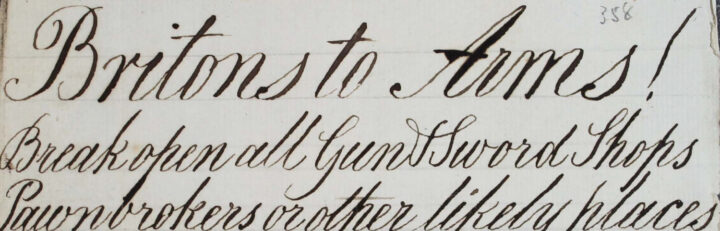

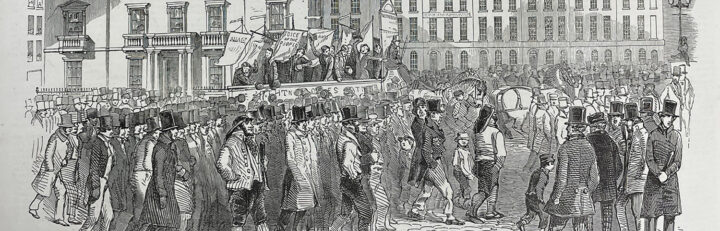

- Protest and Democracy 1816 to 1818, part 1

Was this the start of mass politics in Britain? - Protest and democracy 1818 to 1820, part 2

How close was Britain to revolution?

Lessons

- What was Chartism?

- Why was radical writer Thomas Paine significant?

- What caused the 1832 Great Reform Act?

Political and social reform in 19th century Britain - Mangrove Nine protest

What does this reveal about police brutality and racism in ’70s Britain?