Leaks, scandal and indiscretion

Spycatcher was, at first glance, an unlikely candidate for the title of ‘most litigated book of all time’. Yet it was on its way there, said Chief Justice Davidson, as he sat in the New Zealand Court of Appeal in 1988. It had only been published the year before.

The book included allegations of Russian double agents within the British government, details of an MI6 plot to assassinate President Nasser of Egypt, and the story of an MI5–CIA conspiracy to overthrow a Labour prime minister. It also discussed at length the practices and techniques used by MI5. Inevitably, it attracted great interest from an intensely curious public.

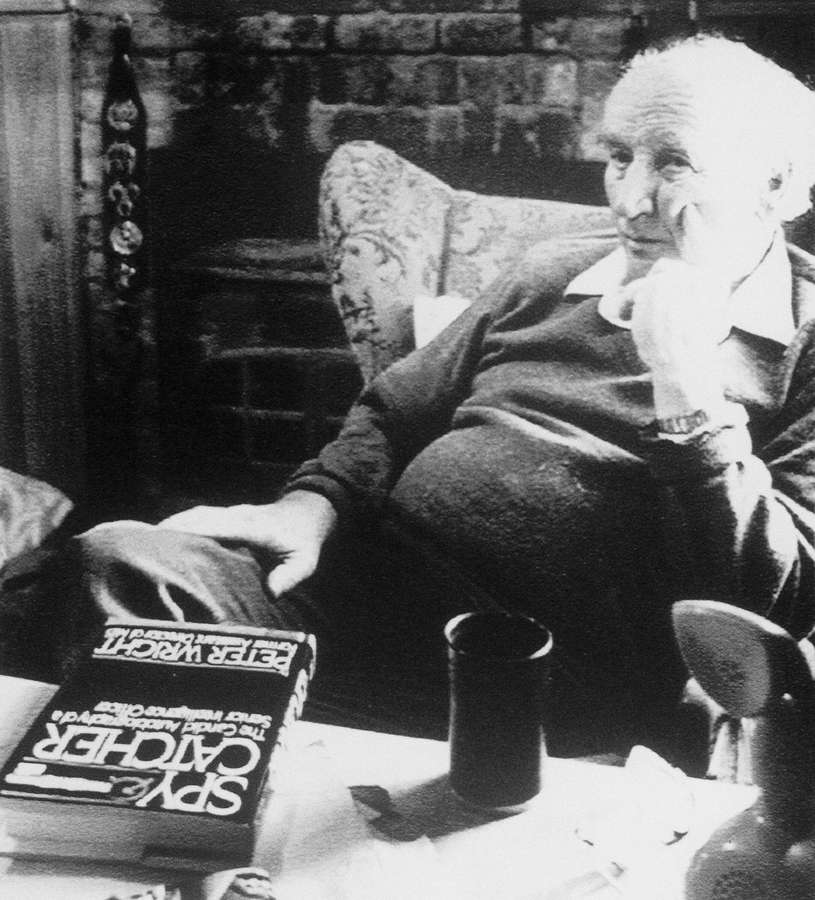

Books about espionage and scandalous tales of Soviet moles, double agents, and the misdeeds of security officers were standard fare in the 1970s and 1980s, authored by the likes of Chapman Pincher and Nigel West. Little within the covers of Spycatcher, however scandalous, was new or surprising. Spycatcher was different in one key respect, however. Its author, Peter Wright, was a retired senior Security Service (MI5) officer, and, in the words of The Times, there was ‘a world of difference between the work of any investigative journalist… and one by a man like Peter Wright, whose knowledge and understanding of Whitehall is so far-reaching.’

Peter Wright speaks to reporters about his court battle, 25 September 1987.

Associated Press / Alamy Stock Photo

This is why the book triggered significant responses from UK government in both the long and short term, which can be traced by reading the Records of the Prime Minister's Office (PREM) held at The National Archives.

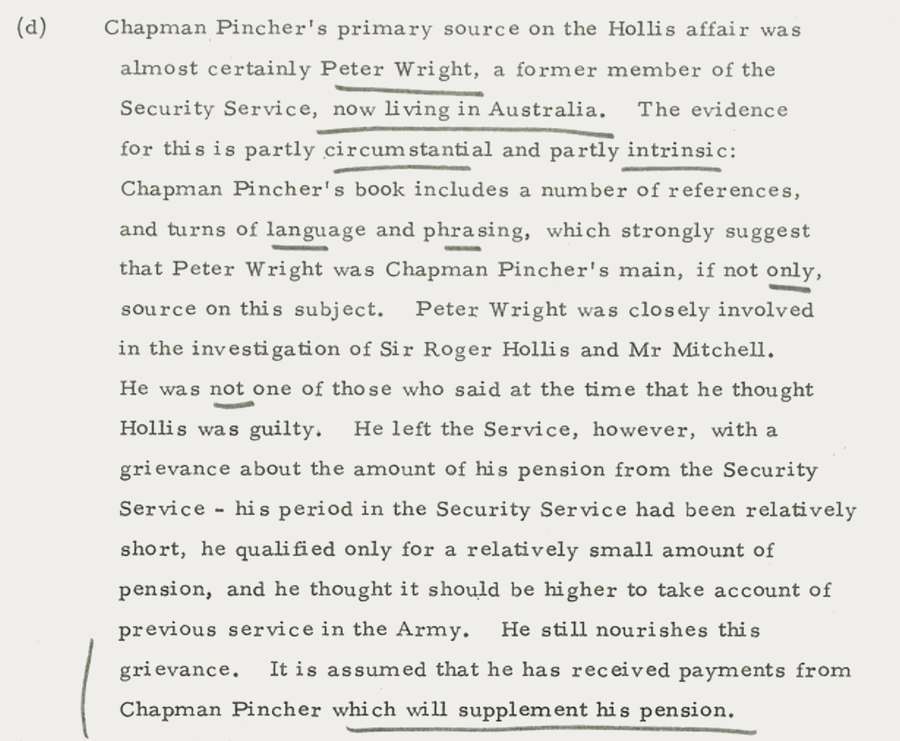

These records confirm, for example, that little of Spycatcher's content was novel precisely because men like Peter Wright had been leaking information to journalists for years. Wright had previously been identified as one of Chapman Pincher’s key sources, in formal legal advice given to the Prime Minister (in the form of a memorandum expanding upon an Attorney General's minute):

(d) Chapman Pincher's primary source on the Hollis affair was almost certainly Peter Wright, a former member of the Security Service, now living in Australia. The evidence for this is partly circumstantial and partly intrinsic:

Chapman Pincher's book includes a number of references, and turns of language and phrasing, which strongly suggest that Peter Wright was Chapman Pincher's main, if not only, source on this subject. Peter Wright was closely involved in the investigation of Sir Roger Hollis and Mr Mitchell.

He was not one of those who said at the time that he thought Hollis was guilty. He left the Service, however, with a grievance about the amount of his pension from the Security Service – his period in the Security Service had been relatively short, he qualified only for a relatively small amount of pension, and he thought it should be higher to take account of previous service in the Army. He still nourishes this grievance. it is assumed that he has received payments from Chapman Pincher which will supplement his pension.

Memorandum concerning the sources of Chapman Pincher’s Their Trade is Treachery, 26 July 1981. Catalogue reference: PREM 19/591

While litigating Spycatcher, the UK government was also seeking to prevent the publication of Joan Miller’s One Girl’s War: Personal Exploits in MI5’s Most Secret Station. They were attempting to manage and respond to multiple stories and publications concerning Security Service ‘scandals’ and revelations at the same time (as discussed in PREM 19/1951/2, PREM 19/1952, PREM 19/2504 and PREM 19/2506/1).

Problematic leaks and indiscretion were not new issues. The same UK government had previously had to deal with Crown servants leaking information for nefarious purposes, as in the case of Michael Bettaney in 1983. It had also had to manage the fall-out from Crown officers leaking information allegedly in the public interest. For example, Clive Ponting had leaked classified documents in 1984 that proved that government statements about the sinking of the ARA General Belgrano were untrue, and Cathy Massiter had blown the whistle on government surveillance of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND), civil liberties organisations, and trade unions in 1985. Selective leaking of classified information had also contributed significantly to the political turmoil and scandal provoked by the so-called Westland Affair in 1986.

If knowledge was power, then the ability to control the flow of government information was essential to the conduct of effective government. Repeated leaks seriously compromised that control.

A series of court battles

Spycatcher was litigated in a series of cases across the Commonwealth, as well as in England and Scotland. Legal action aimed to obtain injunctions preventing the book's publication, to recover the profits accruing from wrongful publication, and, in England, to pursue those guilty of contempt of court.

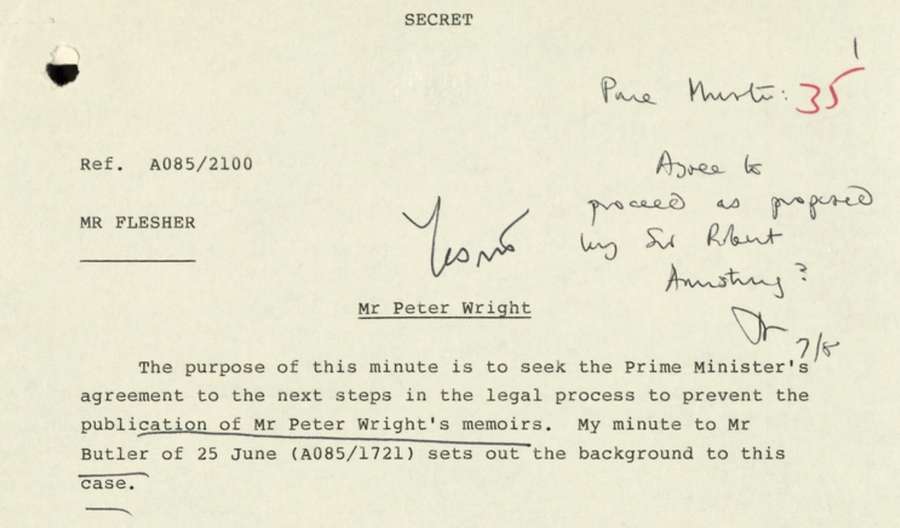

The purpose of this minute is to seek the Prime Minister's agreement to the next steps in the legal process to prevent the publication of Mr Peter Wright's memoirs. My minute to Mr Butler of 25 June (A085/1721) sets out the background to this case.

Minute by the Cabinet Secretary, Robert Armstrong, to Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, 7 August 1985 – lighting the blue touch paper on legal efforts to prevent publication. Catalogue reference: PREM 19/1951/1

They began with action in Australia, where Wright lived, against the author and his publisher. Elsewhere, action was taken against newspapers for publishing extracts or serialised excerpts from the book. They culminated in an appeal to the European Court of Human Rights, where the British newspapers alleged that their Article 10 right to free expression was being breached.

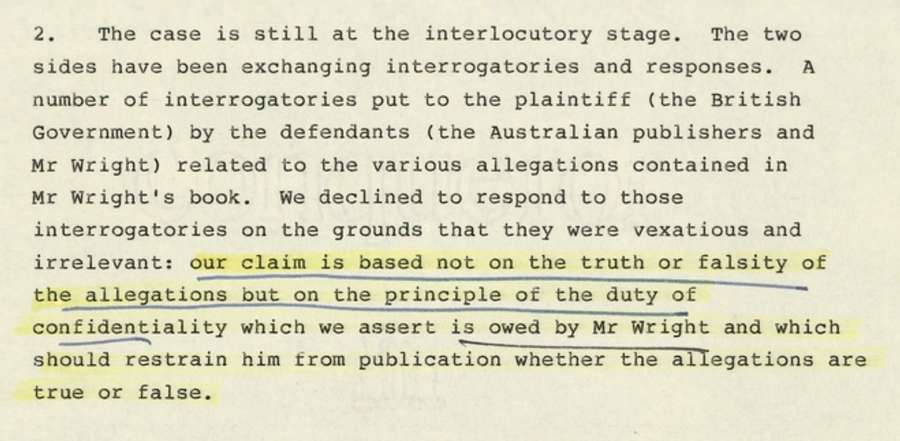

Wherever its legal actions took it, at the heart of the UK government’s case lay the assertion that civil servants owed a lifelong duty of confidentiality to the Crown. They did so because they held, or had held, positions of trust and confidence. The public interest and national security required that they should be held to that duty.

Understanding this is the key to understanding why the UK government continued to litigate long after imported copies of Spycatcher were freely available and their contents widely known. To permit or acquiesce in publication, at least without a fight to the legal death, was tantamount to abandoning the duty of confidentiality.

2. The case is still at the interlocutory stage. The two sides have been exchanging interrogatories and responses. A number of interrogatories put to the plaintiff (the British Government) by the defendants (the Australian publishers and Mr Wright) related to the various allegations contained in Mr Wright's book. We declined to respond to those interrogatories on the grounds that they were vexatious and irrelevant: our claim is based not on the truth or falsity of the allegations but on the principle of the duty of confidentiality which we assert is owed by Mr Wright and which should restrain him from publication whether the allegations are true or false.

Minute on the ‘Wright Case’, 5 September 1986. Catalogue reference: PREM 19/1951/1

Though the UK government ultimately, and at great expense, failed in its efforts to prevent publication, it could nevertheless claim at least a partial victory. The House of Lords, the highest court in the UK at that time, upheld the principle that civil servants owed a lifelong duty of confidentiality to the Crown.

Reforming the Security Service

Historically, not even the existence of the Security Service was officially acknowledged, and neither the organisation itself, nor its activities, had any legal basis.

The role and objectives of its Director General were set out in the non-legal Maxwell-Fyfe directive of 1952, under which they were directly responsible to the Home Secretary. The resulting picture looked like an intensely pragmatic mix of ‘plausible deniability’, ‘need to know’, and what Peter Hennessey has famously called the ‘good chap’ theory of government.

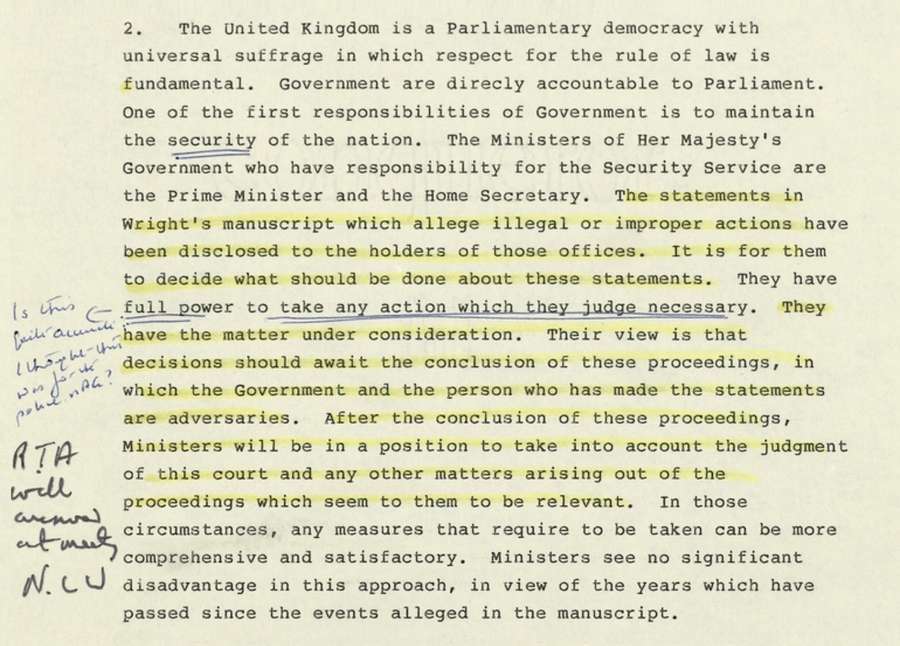

The Ministers of her Majesty's Government who have responsibility for the Security Service are the Prime Minister and the Home Secretary. The statements in Wright's manuscript which allege illegal or improper actions have been disclosed to the holders of these offices. It is for them to decide what should be done about these statements. They have full power to take any action which they judge necessary. Their view is that decisions should await the conclusion of these proceedings, in which the Government and the person who has made the statements are adversaries. After the conclusion of these proceedings, Ministers will be in a position to take into account the judgment of this court and any other matters arising out of the proceedings which seem to them to be relevant.

Minute by the Cabinet Secretary, Sir Robert Armstrong, on the Peter Wright Case, 24 October 1986. Catalogue reference: PREM 19/1952

Even before Spycatcher some modifications had been made to the historical position. The Security Commission, chaired by a judge and staffed by retired civil servants, was created in 1964 following the Profumo Affair. It investigated and reported upon public sector security breaches referred to it by the Prime Minister.

More controversially, following the 1979 case of Malone v Commissioner for the Metropolitan Police, and the subsequent appeal to the European Court of Human Rights in 1984, the UK government had been compelled to pass the Interception of Communications Act 1985, which placed the authorisation and oversight of phone tapping on a statutory footing. This established a system under which warrants were issued by the Secretary of State, the conduct of the warrant system was kept under review by a commissioner who was or had been a judge, and a tribunal heard allegations that an interception had occurred. This provided a model for later reforms to the oversight of the Security Service.

Finally, after the Michael Bettaney case, where a Security Service officer had been caught trying to sell secrets to the KGB, it was proposed that a Staff Counsellor should be appointed. Members of the Security Service could report to this person any concerns they had in relation to their work or that of the Service. The terms of reference and appointment of the first Staff Counsellor, Sir Philip Woodfield, were implemented as the Spycatcher litigation dragged on (see PREM 19/2508).

Despite initial resistance, the controversy over Spycatcher ultimately led to a reluctant acceptance that, in order to restore trust in the Security Service, to silence its critics, and to enable it to operate effectively, further reforms were both necessary and inevitable. Some, like the creation of an official system for vetting memoirs, were relatively uncontroversial. Others were much more problematic – not least because deep divisions persisted between those who desired some form of external oversight, and those who felt that this should be resisted at all costs, as fundamentally undermining the effectiveness and freedom of action of the Security Service.

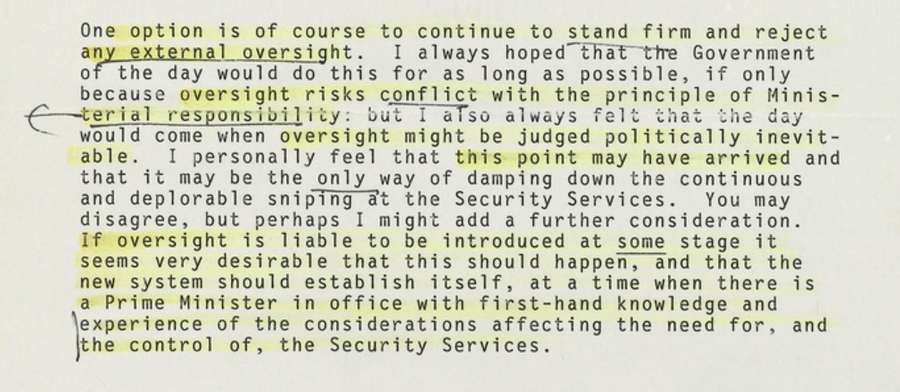

One option is of course to continue to stand firm and reject any external oversight. I always hoped that the Government of the day would do this for as long as possible, if only because oversight risks conflict with the principle of Ministerial responsibility: but I also always felt that the day would come when oversight might be judged politically inevitable. I personally feel that this point may have arrived and that it may be the only way of damping down the continuous and deplorable sniping at the Security Services. You may disagree, but perhaps I might add a further consideration. If oversight is liable to be introduced at some stage it seems very desirable that this should happen, and that the new system should establish itself, at a time when there is a Prime Minister in office with first-hand knowledge and experience of the considerations affecting the need for, and the control of, the Security Services.

Lord Hunt to Margaret Thatcher, 2 December 1986. Catalogue reference: PREM 19/1953

Though the UK government sought to distance its legislative actions from its difficulties over Spycatcher, the Official Secrets Act 1989 and the Security Service Act 1989 were extensively discussed, and piloted through Parliament, as the Spycatcher litigation continued.

The Security Service Act 1989, as seen in its preamble, officially recognised the existence of the Security Service for the first time, placed it on a statutory footing, and created a system of authority and oversight similar to that which existed under the Interception of Communications Act 1985.

The Official Secrets Act 1989 section 1 made it a specific offence for any member of the Security or Intelligence Services to disclose any information relating to security or intelligence, whether damaging or not, which they had by reason of their employment.

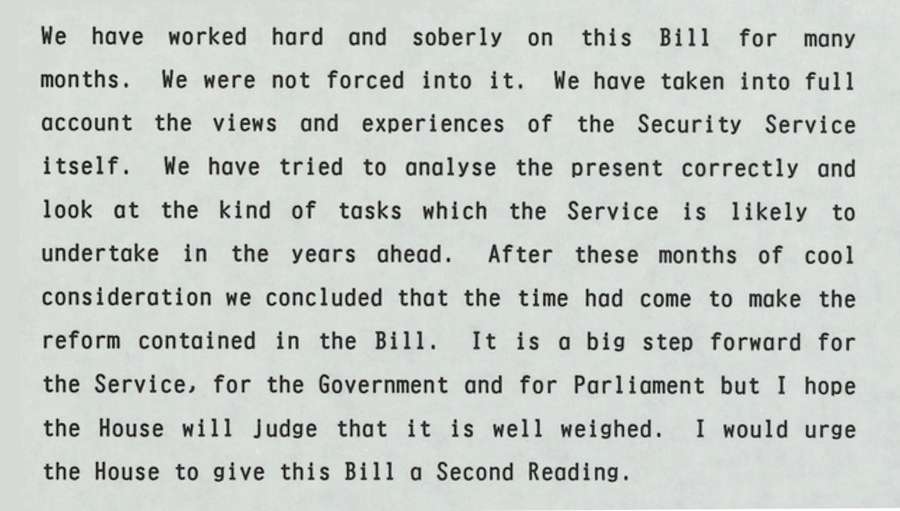

We have worked hard and soberly on this Bill for many months. We were not forced into it. We have taken into full account the views and experiences of the Security Service itself. We have tried to analyse the present correctly and look at the kind of tasks which the Service is likely to undertake in the years ahead. After these months of cool consideration we concluded that the time had come to make the reform contained in the Bill. It is a big step forward for the Service, for the Government and for Parliament but I hope the House will Judge that it is well weighed. I would urge the House to give this Bill a Second Reading.

Home Secretary’s Speech for Second Reading of the Security Service Bill, 15 December 1988. Catalogue reference: PREM 19/2511s

The legacy of Spycatcher

The Spycatcher affair can be characterised as a historic battle over freedom of expression and state secrecy. It also created an impetus for the reform of the Security Service. In both of those respects, it must take its place within the broader history of constitutional reform in the modern era, affecting both the Security Service and government as a whole.

Looking within the files in The National Archives, the links between Spycatcher and the development of Open Government, and later Freedom of Information reforms, are clear.

Spycatcher has a place, then, in the story of the unwritten UK constitution. It shows us how this has increasingly become a creature of law – rather than myriad non-legal conventions and understandings – and how it is now given effect through positively asserted and enforced human rights and obligations, rather than through the old civil liberties idea of freedom within the limits of the law. The Spycatcher affair reveals how the Security Service, just like other institutions of the state, has been moulded by these historic changes.

Records featured in this article

-

- From our collection

- PREM 19/591

- Title

- Prime Minister's Office papers on the Secret Services

- Date

- 8 May 1979 – 12 August 1981

-

- From our collection

- PREM 19/1951/1

- Title

- Prime Minister's Office papers on the Secret Services

- Date

- 16 October 1981 – 9 September 1986

-

- From our collection

- PREM 19/1952

- Title

- Prime Minister's Office papers on the Secret Services

- Date

- 3 October 1986 – 29 November 1986

-

- From our collection

- PREM 19/1953

- Title

- Prime Minister's Office papers on the Secret Services

- Date

- 1 December 1986 – 23 December 1986

-

- From our collection

- PREM 19/2508

- Title

- Prime Minister's Office papers on the Secret Services

- Date

- 23 September 1987 – 30 October 1987

-

- From our collection

- PREM 19/2511

- Title

- Prime Minister's Office papers on the Secret Services

- Date

- 5 October 1988 – 23 December 1988

Read more

- ‘The Judge and the Spycatcher’, The Times (14 March 1987)

- Peter Hennessey, The Hidden Wiring: Unearthing the British Constitution (Phoenix, 1996)

Past exhibition

MI5: Official Secrets

This 2025 exhibition allowed visitors to step inside the hidden world of MI5 and explore the extraordinary stories behind the security of a nation.