The railway

During the 1830s and 1840s, railway networks expanded with astonishing speed. This started in Britain and Europe but soon moved across other continents as well. Suddenly travel became faster, more affordable, and accessible to people who had never imagined journeying beyond their home cities or nearest towns.

This meant that the expanding middle class could now enjoy leisure tourism. But this technological revolution created a practical problem: many people didn't know they could travel for pleasure, much less how to do it. They needed guidance, and the market responded.

Mariana Starke

By the mid-17th century, wealthy families had established what became known as the Grand Tour. This was a pre-planned journey through Continental Europe's cultural centres, designed to provide young men with a sophisticated education.

These aristocratic travellers often produced memoirs. They were written to highlight the author's knowledge and refinement rather than act as practical guidance for future travellers. Accordingly, the Grand Tour established where cultured people should go and what they should do, but not how ordinary travellers might manage such journeys.

Having travelled to France and Italy in the 1790s, Starke recognised something her aristocratic predecessors had missed: families travelling on fixed budgets needed practical help. They struggled with obtaining passports, booking transport, finding accommodation, and managing expenses.

Starke's books – Letters from Italy (1800), Travels on the Continent (1820), and Travels in Europe (1828) – marked a move away from travel memoirs to an early version of practical guidebooks.

Within these guides, she invented a rating system using exclamation marks to indicate venue quality. This transformed subjective opinion into comparable information.

Her publisher, John Murray of London (already famous for publishing Jane Austen, Lord Byron and Samuel Taylor Coleridge), immediately recognised the commercial potential in Starke's work. When Starke published her final book in 1832 and died in 1838, Murray built on the foundation she left behind.

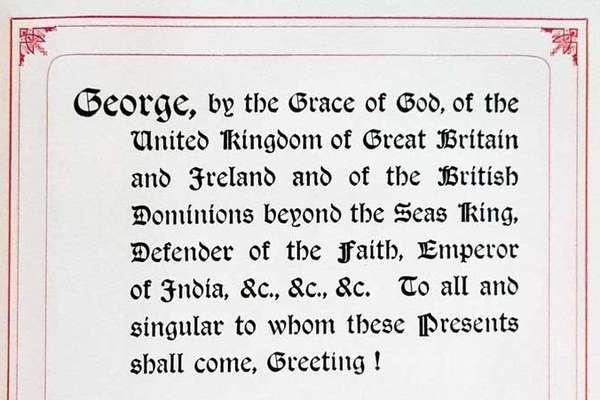

…230, statue of Marsyas!!! This is deemed one of the finest pieces of sculpture extant; and, like every other antique repre-sentation of Marsyas, is supposed to be imitated from a picture by Zeuxis, which Pliny mentions as having graced the temple of Con- cord at Rome…

[...]

Hall of the fighting Warriors. No. 262, statue of a Warrior, called the Gladiator of the Villa Borghese!!!! He is represented as combating with an enemy on horseback; his left arm bears a shield, with which he is supposed to parry the strokes of his oppo-nent, whom, with the right hand, he is about to wound with all his force. The attitude of the statue is admirably calculated for this double action; and every limb, every muscle, is said to wear more precisely the appearance of life, than does any other master-piece of the Grecian chisel...

Starke's rating system as featured in 'Information and Directions for Travellers on the Continent' (1820). Image source: public domain via Getty Research Institute

Systematising travel

In 1836, John Murray launched Murray's Handbooks for Travellers, evolving Starke's exclamation marks into star ratings. The Handbook was followed by guides to Switzerland, Greece, Egypt, France, Italy, and British domestic destinations.

Beyond accommodation and dining advice, Murray introduced the concept of rated sights. This told travellers not just where to go, but what they should see and how important each attraction was.

Around the same time, in Germany, Karl Baedeker acquired a publishing house and began his own travel guidebook series. By 1844 Baedeker adopted Murray's star system. However, where Murray provided practical navigation, Baedeker also offered cultural information, with details on art, architecture, and local customs.

Additionally, Baedeker added comprehensive illustrated maps and plans, ensuring readers could find their way in unfamiliar cities. These guides shaped how travellers perceived places and established which sites' tourism grew based on their cultural appeal.

Both publishers famously used bright red covers with gold lettering, making their books stand out on shelves and easy to locate in luggage.

The National Archives holds over 500 examples of these types of guidebooks, which were transferred from the British Transport Historical Records Library in the 1980s. This library had been created when the records of the various surviving private railway companies of the 19th century were taken over by the British Transport Commission (BTC) upon nationalisation in 1948.

Image 1 of 2

Murray's handbook for travellers in Kent and Sussex (1858). Catalogue reference: ZLIB 19/6

Image 2 of 2

Baedeker's Great Britain (1910). Catalogue reference: ZLIB 19/308

The distribution network

The travel guide needed distribution channels, and William Henry Smith provided them in a very convenient place.

Smith opened the first railway platform newsstand at Euston Station in 1848. This led to Smith successfully selling travel guidebooks to a booming market. But practical travel required more than destination advice.

George Bradshaw's travel guide (originally published in 1839) addressed the logistical issues that came with travelling. This included information and guidance on:

- Coordinating train schedules

- Different time zones and currencies

- Complicated international connections.

By 1847, Bradshaw covered Continental railways, and later expanded to India, Australia, and New Zealand.

This comprehensive guidance led to Bradshaw rivalling Murray and Baedeker. Bradshaw's guides became so well-known that they regularly appeared in popular fiction, including Jules Verne's Around the World in 80 Days.

Image 1 of 2

Bradshaw's Continental Railway Guide (August, 1861). Catalogue reference: RAIL 904/2

Image 2 of 2

Part of a train timetable featured in Bradshaw's Railway guides for Great Britain and Ireland (1912). Catalogue reference: RAIL 903/151

Mass tourism arrives

In 1841, Thomas Cook, a Derbyshire cabinet maker who joined the temperance movement, organised a charter train for 485 temperance society members travelling from Leicester to Loughborough. Charging one shilling each, he realised some travellers valued not having to organise trips themselves.

Cook's first profit-making trip in 1845 took a party to Liverpool, Caernarfon, and Mount Snowdon. By 1851, he had arranged travel for 165,000 people to London's Great Exhibition.

Cook's business grew from temperance daytrips to multi-stage Continental package tours, removing barriers of language, logistics, and confidence. His business created the perfect system for rail travel: railways needed passengers, passengers needed guidance, guidance created demand.

THOS COOK & SON.

Chief Office,

Ludgate Circus, London.

July 3rd 1891.

Sir Dominic Colnaghi

K.B. H.M. Minister General

Florence Italy

My dear Sir,

congratulations of fifty years of the business of Thos. Cook & Son.

Herewith I have pleasure in forwarding copy of a small volume entitled “The business of Travel” which has been compiled for the purpose of recording the life and history of the founder and the present managing partner of our business, & also the origin & development, commencing with the first publicly advertised excursion from Leicester to Loughboro[ugh] on July 5th 1841 & showing at the end of the year 1890 arrangements and booking facilities over nearly two million miles of Railways, Oceans & Rivers.

Hoping the subject will be of sufficient interest to justify your taking an early opportunity of perusing the same,

I am

Yours sincerely

John Cook

A letter from John Cook celebrating 50 years of business by Thomas Cook & Son. Catalogue reference: ZLIB 1/9 p1

Everything is organised, everything is catered for, one does not have to bother oneself with anything at all, neither timings, nor luggage nor hotels.

An early Thomas Cook traveller

Marketing the railway

The guidebooks assisted travellers once they knew they wanted to go on holiday, and where they wanted to go. This greatly impacted Britain’s graphic art and advertising. Railway companies were highly competitive and constantly looked for more passengers. This helped them to succeed in in the growingly competitive tourism business.

By the mid-19th Century, they turned to graphic artists to design beautifully illustrated scenes of the seaside, forests, mountains or speeding trains filled with smiling passengers.

The National Archives also holds many examples of these posters. Mostly, these records became part of our archives from rail company records or due to copyright registration.

Image 1 of 2

London and South Western Railway poster advertising Weymouth (1909). Catalogue reference: COPY 1/282 (119)

Image 2 of 2

Great Western Railway poster advertising Bath Spa (1908). Catalogue reference: RAIL 1014/39 (12)

Consequences: commercial and cultural

The increasing accessibility of train travel transformed the tourism industry. The rating systems in guidebooks pressured accommodation providers to improve quality or risk shame in print and potential financial ruin.

Additionally, popular destinations saw increasing hotel construction, often supported by government tax incentives. Alongside them came new restaurants, bars, and leisure activities competing for tourist attention. Amateur hospitality, such as bed and breakfasts, that were based in the spare rooms of private houses, also grew into professional service industries.

However, the accessibility of travel created concerns. The tourist versus traveller debate emerged, separating those seeking leisure from those looking for a deeper cultural experience.

Some destinations adapted themselves to tourists rather than travellers wanting to experience authenticity from the places they visited. Complaints about tourist behaviour and their impact on local residents became common, especially when tourists took part in excessive partying and drinking while on holiday.

'Not having the tourist mind' by artist Ronald Searle. In this satirical cartoon, the tourist on the left can be seen reading a book by Baedeker. Catalogue reference: INF 3/1106

Despite this, leisure travel created unprecedented cultural exchange. Travel guides became carriers of cultural authority and national identity. This helped shape travel logistics as well as travellers' perspective of places. They made passengers think about what mattered, where to go, what to see and how to see it, and which local businesses to trust all before reaching their destination.

From Starke's ratings to Baedeker's detailed objectivity, travel guides didn't just describe and provide access to places. They shaped them and redefined what travel meant and who could experience it.

The railway provided the means and the travel guide provided the confidence. Together, they transformed travel from a privilege to a real possibility for many.

Today, travel is still something many of us enjoy, in part thanks to the creation of the travel guide. While we might access newer forms of these guides, often on our phones rather than physical books, the core principle remains the same: travel can be for everyone.