From the working lives of medieval women, through the story of the first Women Patrols in the Metropolitan Police, to the striking Ford factory workers in 1968, this episode examines women’s jobs, their conditions, their struggles, and their resilience.

Listen to the epsiode

Listen

Working women in history

Audio transcript for "Working women in history"

Jessamy Carlson: They say a woman’s work is never done... but it has evolved over time.

To mark Women’s History Month, I want to take a very long view at working women, their jobs, their conditions, their struggles and their resilience.

This is On the Record at The National Archives, uncovering the past through stories of everyday people.

I’m Jessamy Carlson, the family, local and community history specialist at The National Archives.

In this episode of On the Record, I’m asking three historians to join me in the studio to explore the lives of working women over the centuries, using some of the collections we hold here at The National Archives in Kew.

Jessamy: Kath Maude is going to guide me through the working lives of medieval women.

Lisa Berry-Waite will tell the story of the Women Patrols in the Metropolitan Police in London, which formed in 1919.

And Vicky Iglikowski-Broad has been exploring how women workers took collective action: from the matchgirls who went on strike in 1888 to the Ford workers in Dagenham who demanded recognition for their skills in 1968.

Jessamy: Kath, Lisa and Vicky, welcome to the studio.

Let’s get working! Kath, let me start with you...

Kath, can I start with you? So women's work, or women who work, that's by no means a modern construct, is it?

Kath Maud: No, absolutely not women's work in the Middle Ages is really varied, as varied as it is today, but it looks quite different, and partly that's because of this kind of Victorian idea of separate public and private spheres. So in the Middle Ages, that wasn't really a thing. You didn't so much have a sense that there was a place outside of the house where work happened and a place inside of the house where work didn't happen, right? And so the household is a workspace. This isn't just the case for women. It's also the case for men. So the king's wardrobe, his kind of private space where he got dressed, was also the place where he'd sign his most personal documents. And so that kind of household space is a space of work, both for women and for men. And so we have a lot of opportunities for women to kind of take part in what we would recognize as work within that household space. So like the management of finances, for example, that was a kind of really important way that women contributed to work, and women contributed to the household through their work.

Jessamy: And it's not just married women who worked, women who were single, women who were widowed they also had employment. So could you talk a little bit about how becoming widowed might change a medieval woman's legal or economic status?

Kath: Yeah, absolutely. So widowhood is a really interesting status in the middle ages. It's kind of it's a bit sexy. It's slightly unusual, you know, and it's slightly troubling. Perhaps it's a status of independence from a husband. But also, unlike a single woman before marriage, you're likely to have a lot more financial independence and kind of independence to do things that you want after being widowed. So under Norman Law, married couples were one legal entity under their husband's name. So we call that ‘covert du baron’ literally covered by a baron, covered by your husband. Yeah, I know it's kind of a kind of a ridiculous name, but upon widowhood, women kind of come out from under their husbands in whatever way you want to take that, apologies! And so they become legally visible, and they can manage their own property and debt, so they become a ‘femme sole’, a lone woman.

Jessamy: And I guess that's because single women are still under the jurisdiction of their fathers.

Kath: Absolutely, whereas the widow kind of comes out from under the father comes out from under the husband, and becomes a kind of woman in her own right and becomes a legal kind of figure in her own right. And so they can chase their own debts. Often they would chase their husband's debts after, after he died, they could manage their own estates. They were probably managing the estates before, but we only see them managing the estates afterwards. So if you think about a lot of kinds of noblemen in the Middle Ages, they would often be 4, 5, 6, 7 years off in Scotland, fighting the King's wars, or on crusade, you know, they would be out of the country, or in France in the 100 Years War, right? So they'd be away for a lot of the time. And so once they kind of but when the women were chasing debts or managing the estate, they would do all of that under their husband's name while they were married. So that's they, their work is kind of invisible, whereas after the marriage happens, or after their husband dies, they become able to kind of manage that stuff on their own.

Jessamy: Do we have any documents or items that speak more to that evolving nature of women's status?

Kath: Yeah, absolutely so. One of my very favourite documents, which I think also speaks a little bit to the sexy nature of widows that I was mentioning earlier, is this seal of a woman called Ermengarda, which also, I think is a great name. I don't know if anyone's got any cats they need to name Ermengarda, perhaps. So we have this seal on a receipt given to the Treasury. So Ermengarda is a widow, and she says this explicitly in the in the receipt, a widow of a Knight called Henry de Sancto Mauro, and the receipt says that she's received a payment from the Treasury that she was owed for the rent of a manor that she that she owned. So she's renting out her manor house to the Treasury. And on her seal, there's an image of her wearing a widow's headdress, which is sort of a big sweep, a big sweep of headdress. And this is very unusual. In general, we don't have images of women on their seals at all, noble women or kind of royal women, even it's not very common. But also she's kind of advertising her widowed status by having the widow's headdress. And she also is wearing quite a low-cut dress on her seal. So there's this image of her kind of saying, I am I am financially independent. I can prosecute my own transactions. And, you know, maybe I'm available to marry again. You know, that might be something I'm looking for.

Jessamy: So finance records can be quite an interesting way of looking at women in the past. Yeah,

Kath: Yeah, absolutely. And I think women's work in general, we can really see during… in some of these more… what we might think of as more boring records that tend to be lists of people's names and the taxes that they paid. So for example, we have in our E179 Database, that is our Tax Records Database. We have a lot of evidence of women's women paying money. So for example, we have a document. It has a long document reference. It's E179/180/111, and what this document is, is a record of tax on first-generation immigrants by the Crown. And so we know that these are immigrant women. And in particular, we have these two women who I wanted to mention, who are Dutch women living in Suffolk, so Catherine Peterson and then another excellent name, Marion Dutchwoman. So we're pretty confident she's Dutch, even if the record didn't say, and they both work for brewers and are brewing in their own right. And brewing is quite a common medieval activity for women.

Jessamy: And are there other roles that you see referenced in these records that are common to women who perhaps aren't as elite as Ermengarde say?

Kath: Absolutely, that's a great kind of distinction. So we have these gentlewomen who are managing their houses, who have a lot of property and land and money that they have to manage and think about and then you have women who are working more for a wage or for kind of piece work. So we have the Brewers who are selling their beer. That's a very, very common kind of work for women, but also sewing and embroidery. So we have a nice example of a woman called Henry de Sancto Mauro, who, in 1241, is given 100 shillings to finish the King's chasuble, which is a kind of robe that the king would wear. And that's in one of our again, a kind of financial document, a payment roll that C6215, we call a liberate roll. So a kind of financial document that tells someone in the exchequer to pay money out. And so this woman gets paid for this kind of piece work. She does this one piece of sewing for the king. And sewing is one of the few guilds that allowed women to take apprentices. So we see sewing and brewing as very kind of typically female jobs in the period.

Jessamy: Did we see other crafts as well, things like I'm thinking of, like lace making, those types of things, obviously, are regionally associated, but I imagine there's a lot of women's work in particularly like Nottinghamshire area around, around lace work and other parts of the country too, obviously.

Kath: Yeah, absolutely lace-making is a really good example. We also see kind of small-scale weaving, basically, kind of thinking later, what we would see is kind of piecework. So my grandmother, for example, she used to knit knitting patterns in her house. So they would send her the pattern, and she would knit the knitting, and then they would take photographs of her knitting for the front of the knitting patterns. So it's a job you can do in your own living room. It's something that doesn't need loads of materials and can often be one or two women, so you can do it alongside other things. So you can brew small beer, for example, while also perhaps looking after children, or, you know, doing things in the household. So it becomes a kind of job that's really, really suitable for women who have other responsibilities, and it's very kind of gendered role.

So this is one thing that we can see with a really interesting figure. I think that really tells us some interesting things about women's work called Eleanor Rykener. We actually don't have documents relating to Eleanor here at the National Archives, but she is a trans woman figure who is found in documents at the London Archives. So the London Archives is fairly close to close to us here in Kew there, across the cross, the other side of the city. And the document, again, is one that we might not immediately think of as telling us things about women. So it's a document with the catch catchy name of Plea and Memoranda Roll A34. Extremely snappy. And that document is a document that tells us about legal cases heard in front of the mayor and aldermen of the City of London. And so this woman, Eleanor Rykener, was caught in on the 11th of December 1394, on Cheapside, having sex with a man called John Britby in the street. And she's hauled up in front of the mayor and aldermen in the new year. So in 1395 and in the process of this court case, she's talked about, she's kind of introduced as John Rykener, calling themselves Eleanor.

The document is a really, really interesting one, because it talks about Eleanor using both male and female pronouns in the Latin. But the reason I'm bringing this up in relation to women's work is that Eleanor was a sex worker, and that's what she was doing when she was caught. You know, she discusses that she took money from John Britby. So the court record actually begins by talking about Eleanor as John Rykener calling themselves Eleanor. And the record (which is in Latin, although in court, the court case would have been taken place either in French or in English) uses both male and female pronouns for Eleanor.

But the reason I'm talking about Eleanor in relation to women's work is that we know that she was a sex worker. But also she works in her testimony she tells us that she works both as a seamstress and as a brewer. And there's some really, really nice scholarship that's come out quite recently talking about Eleanor taking up these female jobs as kind of gender affirming jobs. They're jobs that kind of show her to be the woman that she feels she is, right. So I think that's a really nice example of a woman working in the past in a place that we perhaps wouldn't expect.

Jessamy: I think there's something interesting about how we talk with sewing. With women, it's sewing, and with men, it's tailoring. And I know that's a more modern distinction, but I do think it's quite interesting that when we talk about men who sew, we generally talk about men who sew, we're generally talking about tailors.

Kath: Yeah, or embroideries in the Middle Ages, actually, that's the kind of distinction you have the Embroidery Guild and women are kind of sewing. So yeah, again, it's that distinction between small-scale and large-scale industry, or industry that can be done in the household and industry that can be done outside the house. So yeah, I think that's a really important distinction that think we'll see kind of going through the other periods that we're going to talk about.

Jessamy: I wonder if we could touch on the challenges of tracing women in the past, particularly in the Middle Ages.

Kath: Yeah absolutely. I think one of the interesting things is that a lot of these challenges and Vicky and Jessamy and Lisa, you can kind of tell me more about this, like this. Some of the challenges, I think, are quite similar. So one of the big ones - and I know that you trace people, Jessamy, through the census all the time - is that their names change on marriage, right? And that is a big problem. So in the later Middle Ages, once surnames kind of settle down, we're often kind of struggling to trace women because they change their name, but also, women will often use their husband's seals or their father's seals to seal documents. So even if they are doing the work themselves, they're kind of using the signature or the authority. Man in their lives to get things done, either officially or unofficially. And then the other thing, I guess, is that when women are managing estates during their husband’s absences, all of the documentation would still be in their husband's name. So even if their husband is, you know, in Scotland, if they petition, if the woman petitions, the King, the petition will be in the name of their husband. And so a lot of the work that women do in the period is really hidden in that way. And I think that that's something now we can hear a little bit more about this, but I think that's something that kind of continues throughout history. It's not something that just happened in the Middle Ages.

Jessamy: Yeah, I think there's something interesting around where women's work is masked in that formal way. But then I've also seen in 19th century census records, particularly in 1841, where the entries for married women the occupation, has clearly been rubbed out. You can see that someone has evidently gone back, because the forms are filled in in pencil, so it's not they've been crossed out. They've been rubbed out. You can just about make out the indentation on the original paper. So that is literally erasing the work of women in the past, which I think is quite an interesting concept, that not only is it invisible, but when it is made explicit, it's then removed by men in positions of power, in this case, enumerators from the official record, right?

Kath: Absolutely. And one of the things we have to remember about the National Archives is that, you know, it was collected, all of this material was collected together in the 1830s and the 1830s is a period when the Public Record Office was originally founded, where women's work is taken less seriously, right? And so I think the ways even that things are indexed, for example, will kind of hide some of that work that women were doing or our seals card index, for example, often women are indexed under their husband's name, and so if you're looking for women, you can't find them, but that's an indexing problem. It's actually not a problem of the original record. It's so that's another kind of archival challenge that I think will be recognizable, kind of across time.

Jessamy: Thank you so much. Kath.

Kath: Thank you.

Jessamy: I want to move on to a specific job and find out about the history of women in the police force. Lisa, I’m hoping you can help me with that.

Lisa Berry-Waite: Hi, Jessamy, yes, absolutely. So I now work in the Heritage Collections Team in the UK Parliament, but I previously worked at The National Archives, and I did a bit of research on women in the Metropolitan Police, so I'm glad to be talking about that today.

Jessamy: Brilliant. Thank you. So the Met Police have a long history, but for a long time it was a male-only service.

Lisa: Yes, absolutely.

Jessamy: So when did women first join the Metropolitan Police?

Lisa: So this was in 1919 when the Metropolitan Police Women Patrols were formed. So this was the first time that women were formally inducted into the Metropolitan Police. So as a little bit of context, women had been involved in policing before this. So for example, during the First World War, there were unofficial bodies of women who undertook police duties. But it was in 1919 that it was decided that the work of the women police would come directly under the Metropolitan Police. So the records in the Home Office and the Metropolitan Police held at The National Archives offer us a wealth of information about the women patrols. But I think it's really important to highlight that the experiences of these women would have been very different to that of male police officers. This can be seen in an application form held at The National Archives for women to apply to join the Women Patrols, which listed the various qualifications needed to apply.

So there were age and height restrictions, so you had to be between the ages of 25 and 35. You also had to be taller than five feet four inches, and in brackets, it said without boots on, which I find quite comical. So I definitely wouldn't have been eligible to join the Metropolitan Police Women Patrols. And then women who had young children, depending on them as a rule, weren't eligible to apply either. But what I find quite interesting is that initially, women who were married were able to apply and become members of the Women Patrols. But there was actually a marriage bar introduced in 1927 so this applied to all new female officers joining from that from 1927. So although it didn't initially apply to existing married women in the force, this came into effect in 1931 and the recruits for the women patrols came from all classes, but it did tend to be largely middle-class women, and often those who had some experience of social work was seen as a really valuable asset. So after that, you would apply and were successful, you would then go and do five weeks of training before, before joining.

Jessamy: So what were the key differences between the work that male and female police officers are doing at this point in time?

Lisa: Yes the duties of the Women Patrols were quite different to that of male police. Officers. So a lot of their work focused on matters relating to women and children. So it was very gendered. So for example, escorting lost children, taking statements from women and children involved in sexual assault cases, patrolling parks where women were thought, to, quote, “be drifting into an immoral life”. So essentially, undertaking sex work and a lot of general welfare work as well. Women also carried out seven hour shifts on duty, so one hour less than the men, and they didn't work on the streets after midnight either, and it was also really poorly paid, and they weren't entitled to a pension at the time either.

Jessamy: That’s interesting that the disparities between men and women in the same service are so stark and so clearly set out. Can you tell us about any specific officers experience in the in the these early days of the Metropolitan Police?

Lisa: Yeah, so one person that comes to mind is a woman called Lilian Wyles, and The National Archives actually holds a photograph of her, pictured in her Women Patrol uniform, so she's facing the camera. She's got quite a serious expression on her face, and she's wearing a dark tunic, her skirt boots and a police hat, and the collar of her tunic has the letters MP, which stands for Metropolitan Police So, and it's also, yeah, really nice to see that photograph of her to put her name to the face as well. So Lillian joined the Women Patrols in 1919, and after only a few months, she was promoted to sergeant.

So in this role, she supervised the work of the Women Patrols in central and the East End of London. But before 1923 women didn't have the power to arrest anyone, which I'll talk a little bit more about later on. So Lillian talks about how if she wanted to arrest anyone, she had to then go and very quickly find a male police officer to come and help her arrest someone. So as you can imagine, that would have been very kind of difficult and tricky to do, and she was really vocal on this topic as well. She wrote in a newspaper article that, “This action of rushing up and down to find a constable may be meritorious for the voluntary patrol, but when undertaken by a member of the force having status, authority and defined powers it becomes undignified, if not ludicrous.”

So I think this quote from her just really highlights the challenges that Lillian and her colleagues were facing. And then two years later, in 1921 she is promoted to inspector, and she becomes attached to the Criminal Investigation Department, so the CID, and she writes in her autobiography that she wasn't wanted in the CID. So I think this really shows how she and her colleagues were often met with resistance from male police officers. In this role, she often took statements from women and children related to sexual assault cases. And The National Archives actually has her annual qualification report from 1937 which is a really interesting source, and it says that she's performing well at her job, and her work entails various inquiries concerning females and juveniles, in addition to a great deal of welfare work. But what I find really interesting about this particular source is that the questions on the report use the pronoun ‘he’, and it's had to be crossed out with ‘her’ put in instead. So I think that kind of really emphasizes that male police officers were very much seen as the norm at that point, and that the forms weren't changed to include he and her pronouns.

Jessamy: Yeah, we see that in the First World War nursing records as well. So there are officer reports, which are also used for nurses. And nurses, military nurses at this point are exclusively female in the services to which these records were related, and all of it has had to be gone through. And yeah, her for him, and she for he, you can see the ‘S’ is carefully written on the form so that the form relates to the person it's describing. So I think that's quite a common experience of women in positions which have previously been dominated by men.

Lisa: Yeah, I think definitely a lot of interesting similarities there.

Jessamy: Can you talk a bit about why women's arrest powers were controversial?

Lisa: Yeah, so initially, women weren't sworn in as constables, so they didn't have the power to arrest like male police officers. So essentially, when they wanted to arrest someone, as I said, they would have to find a male police officer to help, and this was because they were seen as kind of physically unfit for the task. So, for example, the Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, Sir William Horwood, said that “if they were sworn in, then they would have to carry out certain duties which, as must be obvious to everyone, they are not physically fitted to before and I should hesitate to accept the responsibility of any of these women being called upon by the general public.” So I think that kind of speaks volumes that the commissioner of the Metropolitan Police was kind of saying that at the time. So yeah, I guess highlighting the kind of prejudice and criticism that the women patrols were kind of coming up against. And a lot of male police officers just didn't think that work was kind of really necessary. Nancy Astor and Margaret Wintringham, who were two women MPs at the time, so Nancy being a Conservative and Margaret being a Liberal, and they actually campaigned in parliament on this issue and for women to kind of gain the power of arrest. So this was finally achieved in 1923 and they were given the name women constables. So yeah, they now finally had the power to arrest as the same as the male police officers.

Jessamy: So was the inclusion of the women in the Met Police ever under threat?

Lisa: Yes, it was so after only three years in operation, the women patrols risked being disbanded altogether in 1922. The Home Secretary, Edward Shortt, was urged by the Geddes Committee (which was essentially a committee on national expenditure) to disband the Women Patrols as a way of economising. So it actually recommended the removal of all women holding positions as police officers. So as you can imagine, yep, this caused uproar from the interwar women's societies, from the women MPs and from the press as well. The Home Secretary then received a deputation organised by the National Council of Women, which urged against its disbandment. So 65 societies were represented at this deputation, so a huge a huge number, and both Nancy Astor and Margaret Wintringham were among the delegates as well. Nancy actually opened the proceedings by stating, “It is one thing to economize and another thing to abolish the women police.” So this was followed by a number of speeches which emphasised the valuable work of the woman police but the Home Secretary said that “while he recognised the value of the women police work, it could not really be described as proper police work. It was more in the nature of welfare work.” So again, I think a really interesting quote there kind of highlighting that prejudice that women were facing.

Jessamy: So it's interesting to see Nancy Astor here. She undertook a huge amount of work for women and families across the first half of the 20th century, but I know she also held some problematic views.

Lisa: Yeah definitely, so although she was the first woman to take her seat in Parliament and championed lots of women's issues, she also is quite a problematic character as well, in that she held, for example, held anti-Semitic views. So I think that kind of shows that looking back on history, often the people that we're studying from modern-day perspectives, we don't always agree with their views.

Jessamy: Absolutely and I think even when they've achieved great things in their career, we can disagree with other aspects of the views that they held.

Lisa: So it was eventually decided that the women patrols wouldn't be disbanded altogether, but they were actually cut to just 20, so a really tiny number, although this did gradually increase in time. And of course, like I mentioned earlier, the marriage bar came in in 1927 so that had a lot of implications for women wanting to join the Women Patrols, and accommodation was another issue. So they were supposed to be provided with accommodation, but there were a lot of challenges around this. So for example, in 1921 all the accommodation for the women patrols was actually full. So there were 21 single women who did not have accommodation, and 30 married women living in their own homes as well. So this would have been much harder, potentially, for women to join the Women Patrols with this kind of lack of accommodation. But really interestingly, in the 1921 census, which I know Jessamy, you'll be very interested in, there's actually a group of women patrols living at Section House in London. So that was really interesting to find, to find their census record.

Jessamy: Interesting. Yeah, you do find some great institutional records in the 1921 groups of women, particularly nurses' hostels, there's quite often long lists of working women in those settings. It's interesting to see that historically, there is that expectation that a job would provide accommodation in that way. And obviously that's something that's changed quite significantly over the last century.

Lisa: Yeah, definitely.

Jessamy: Great. Thank you so much. Lisa. Really appreciate it.

Lisa: Thanks Jessamy.

Jessamy: One topic that's been coming up so far is how working women have had to protect their right to work and to attain certain working conditions. And I want to find out more about this, and I'm hoping I'll be helped by Vicky Iglikowski-Broad, who is a specialist in diverse histories here at Kew. Hello Vicky.

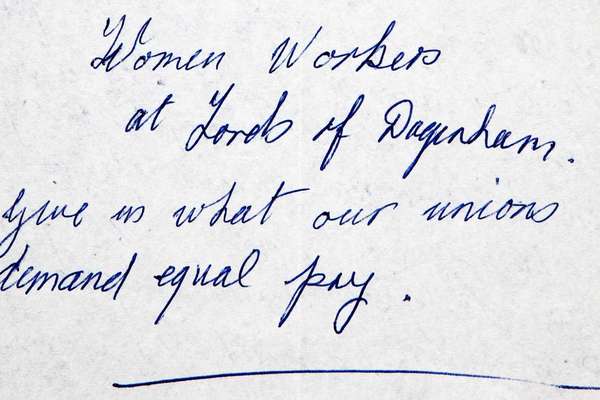

Vicky Iglikowski-Broad: Hi, Jessamy. So to look at this topic, I wanted to start with a quote, and it's from our records. So the quote goes, “We are fighting a great fight equal pay for women. We at Fords have started the ball rolling. Our unions are backing us. Funds are coming in. We're all set for battle. Fords is the beginning. Soon it will be every industry in Britain out because of us women of Fords, we will force you to give us all equal pay or strike with our union's blessing.”

Jessamy: It's a really powerful quote. Can you tell us more about the story?

Vicky: Yeah, absolutely, so. This is a handwritten letter sent to the Prime Minister Harold Wilson by sewing machinists at Ford's car plant in Dagenham in the late 1960s. So if you've heard of the film Made in Dagenham, this is very much those women, and they were on strike, partly to try and get equal pay. But this is just one example of how women have fought for the right to work, for the right to equal pay and for the right to have good working conditions.

Jessamy: Yeah and I think that fight in itself is a long tradition. I've seen preparation files for the 1921 and 1931 census showing female members of the census team and male members of the census team doing the same job on the same line, but men and women clearly and completely legally paid different wages for the same work. So Vicky, have you found other earlier examples like this?

Vicky: Yeah, absolutely. This is quite a strong theme in the collections. So a really famous example is a strike led by women workers, known as the Matchgirls’ Strike from 1888 so at the time in the 1880s the match trade was booming, and one of the largest factories in London was the Bryant & May factory. So there matchgirls worked. They were known as matchgirls, but actually that refers to women and girls, and they did lots of jobs, like dipping, cutting, boxing matches. So really a range of roles in the factory. But in these roles, they engaged with dangerous chemicals. So there was a lot of risk involved in this kind of work. So it was particularly white phosphorus that was a really risky chemical.

Jessamy: And so phosphorus is not nice stuff?

Vicky: No. So their work really actively engaged them with this kind of dangerous material. And the phosphorus was a way of having quick, easy lighting matches, but had these really harmful consequences for the matchgirls. So it actually caused an illness known as phossy jaw, and that had a horrible impact on the individuals. So it would damage things like teeth. It potentially caused brain damage, loads of horrible impacts. And we do have lots of records around these health impacts in our Home Office files, and some of those actually show the real detrimental impact. So 19.15% of individuals who got ‘phossy’ jaw ended up dying from it. So if you got it, you had a one in five chance of dying.

Jessamy: And I guess we see parallels with the Canary Girls in the First World War? Girls who turned yellow because of their exposure to chemicals in the workplace. So clearly that was an issue, which has come up time and time again.

It would be interesting to reflect on what role class plays in these strikes. A lot of these conditions you're describing are factory work, which is notoriously badly paid. It would be great to hear your insights on this.

Vicky: So class was a huge factor. So it wasn't uncommon for children to work in factories at the time. So this particular factory, Bryant & May had girls as young as 14 there. So really young, and it was all about the household wage. They needed as many people as possible to be earning, and they were essentially trapped in a system of low pay and bad conditions. And we can see that the phosphorus had a particularly negative impact on them, almost because of how poor they were, their nutrition was bad, their dental hygiene was often bad. And so it meant that all these things made them less fit to fight off illness and disease. So there were lots of things like that that were really, really difficult. There was also a fear of losing work if they were reported as having these conditions, or reported the bad conditions in the factory.

So really, poverty kept them in this, this bad condition, these bad working environments. And there was this kind of practice at the time, which was docking of wages. So the factory foreman would dock wages on the basis of really ridiculous things like chatting while at work or not having shoes on. And these were really poor women that maybe didn't have all these opportunities. So to dock their money and their pay for those kind of reasons was really harsh, and it was actually one of the factors that led to the strike. So although it was also a question of the unhealthy working environment, one of the things that really pushed them to strike was also that that docking of their pay.

Jessamy: And I think in this period as well, we sometimes forget that the right to an education, the right to be in school, isn't enshrined in English law until 1918. That's when the Education Act comes in, and at that point, it's still only up to the age of 12, so the opportunities for children to be employed is still a major issue well into the 20th century.

Vicky: Yeah, absolutely. And I think the fact that these young girls were behind the strike shows that they were kind of like having to act old before their time, like you say, not having that that kind of education right. But also having to hold a lot of the family together with their wage as well as other family wages. So there's lots of kind of class things at play.

There was also limited worker protection at the time, so factory acts were slowly being introduced. But the trade union movement was also quite different at the time from now, and the matchgirls were known as unskilled workers. And so trade union movement had traditionally been formulated around trades, so craft professions and things like brush makers guilds and so actually, it was a really important movement at the time to recognise that even unskilled workers, as they were so called, deserved fair rights and deserve to organize collectively and to potentially go out on strike.

Jessamy: And were there any key people outside of these groups of workers who were integral and paving the way towards that action or that recognition?

Vicky: Yeah, so what actually ended up happening was Annie Besant, a Fabian socialist and theosophist, wrote an article entitled “White Slavery In London”, and it exposed the conditions at Bryant & May. She spoke to matchgirls themselves and got their opinions on their their pay and their working conditions. And what she tried to do with the article was to encourage a boycott of Bryant & May products, and maybe even bring kind of libel action by getting them to try and dispute what was said in the in the article that she published. But what actually happened was a little bit different. So she exposed the conditions, and essentially Bryant & May tried to push the matchgirls to dispute what had been said and to refute it. But they refused to do that. They stood by what had been said. And the factory then dismissed some of the girls and also gave them very, very low hours, so they had no work. And it was on that basis that actually 1400 women walked out of the factory and essentially brought, brought everything to a close. So it was a huge impact, and Annie Besant was a really important part of the strike action by exposing this, but it was actually the matchgirls themselves that took that final action and made the decision to take matters into their own hands. So it was a really, really important moment. But allies were really important, and they had allies in Parliament as well, like Charles Bradlaugh, and that was really important to get in this conversation about white phosphorus and its harmful impacts into the heart of government. And that's why a lot of the records we have been generated in Home Office files, because of the medical concerns.

Jessamy: So in 1968 by the time of the Ford worker’s actions, how did things play out differently in that example of industrial action?

Vicky: Yeah, so it's slightly different. So for a start, there's a smaller number of women involved, but the impact is every bit as big. So in June 1968 187 women who were sewing machinists at Ford Motor Company in Dagenham went on strike in this instance, and this action was led by Rose Boland, Eileen Pullen, Vera Sime, Gwen Davis and Sheila Douglass, and their jobs had been regraded to less skilled grade than the men's, so it was like a regrading exercise across the organization, so they were then being paid 85% of the rate that men were being paid. So this was a question of equal pay, but it was also a demand for recognition of their work and their labour to be seen as skilled and as seen as skilled as the men that they worked on all side. So the women workers on strike at Ford Dagenham Plant collectively wrote this letter that we heard from earlier, to the Prime Minister, Harold Wilson, and they really clearly articulate their demands, and they detail the support they had from unions and MPs as well, saying, “we're all ready for battle”. I think really powerfully this letter was signed by the women workers at Fords of Dagenham. So there's a kind of power in that collective and almost kind of anonymous in that letter as well, but working together.

Jessamy: So can you talk a little bit about the immediate outcome of that very powerful letter, and then the long term impact that that action had that rippled across the later half of the 20th century?

Vicky: Yeah, absolutely. So the impact of that letter can be seen in the context of the file. So there's lots of fraught government backwards and forwards, correspondence, telegrams, and we know that the removal of these women's labour led to the production of 2,200 cars being halted, and the cancelation of export orders worth more than 8 million. So it was really crucial, and the fact that these women kind of articulated their own experiences alongside that is really powerful. There was a process of negotiation. Barbara Castle was involved and sent by the government, which again shows the importance of this, that they sent such a key government representative along. And through the negotiation, the women's rate of pay was increased to 90 to 92% of the men's rate. So what's really interesting is that they didn't actually win all their demands, but they did put this really important issue of equal pay on the political agenda, and that's really similar actually, to the matchgirls, who essentially shifted the conversation around working conditions and wages and gave a lot of visibility to the kind of cause that they had. And in both instances, they didn't quite win what they were looking for. So it took a few decades, actually to get white phosphorus banned in in factories, but what they did manage to get was this, the stopping of docking of workers pay at the matchgirls’ factory. So it's hugely influential in both cases, that these strikes pushed for such significant things. In the matchgirls’ strike, it was also really significant as an action by unskilled workers, and that actually pushed for, or was an instigator for, a whole movement called New Unionism, which kind of tried to galvanise, larger groups of membership and more radical action. So that had an impact on the union movement itself, and so did the case of the Ford Workers. So we see after 1968 there was a huge rise in female membership of trade unions. So it's really interesting to see the kind of immediate impacts, but also longer term as well. And we can then see that in legislation like the Equal Pay Act.

Jessamy: And I guess behind that legislation, behind those presses, there's a wealth of historical records that help us to understand these strikes. Could you talk us a little bit through some examples of those types of records that you've been looking at?

Vicky: Yeah, absolutely. So the different cases do pick up on different kinds of records. So in the matchgirls, it's often Home Office records where they're really concerned about these conditions, the factory inspectors that are very much involved and in looking after these spaces. But even within the Home Office files, we get quite a lot of medical reports. So it's an insight that you wouldn't necessarily expect from home office records. With the strikers at Dagenham, there's a real awareness of the financial impact and the impact on imports and exports. So it's discussed at the highest level of government. So the record that I was reading from whether we have this letter, is actually in the Prime Minister's Office files. It's really not where you'd expect these women's voices to be. But it was concern, a concern that there was that high priority at the time. We have other records, Arbitration Records, sometimes we have Treasury Records, sometimes relating to these themes where money is concerned. So there's maybe unexpected places we find the voice of striking female workers. So within these formal government records, there's actually really quite surprising things that we can find about the experiences or voices of individuals, from matchgirls being impacted by phossy jaw to the voice of the strike leaders themselves and the Dagenham Case. So it's a really strong collection, always best used with other kind of archives and sources that reflect maybe the union archives and or the local picture. But it's really, really rich, and I've only focused on two examples, but actually, we have so many that we could pick up on. There's mass walk outs of factories by female workers in the First World War. There's the Grunwick strikes led by South Asian women. And we even have strike bulletins from those. So I think the collection shows that women from all backgrounds, from all over the country have always fought to make the workplace essentially better for those that come after them.

Jessamy: I think there's an interesting resonance there with the census returns for 1911 and to a lesser extent, for 1921 where you have an official record, which people then use for protests. So in 1911 there's lots of suffragettes scrolling all over census entries or refusing to answer questions. And then by 1921 there is still a little bit of. Dissent around women's right to vote, but there's also something around the returning soldiers experience to the home front and their protests about their experiences in life. It's where people have an opportunity to speak truth to government, and they take it, not knowing whether anyone's going to see that. And yet, 100 years later, we're able to look at this as a really rich resource of people's voices. So thank you so much Vicky and Kath and Lisa. These are some great stories about the role of the working woman through history.

Jessamy: In the UK, the 2010 Equality Act requires employers to pay men and women equally for the same work. But the gender pay gap persists, so organisations with more than 250 employees are now required to publish data on their gap. In April 2024, the gender pay gap for full-time employees was 7%, down from 7.5% in 2023.Slowly, the gender pay gap is becoming history.

Jessamy: Thanks for listening to On The Record from The National Archives. To find out more about The National Archives, follow the link from the episode description in your podcast listening app. Visit nationalarchives.gov.uk. to subscribe to On the Record at The National Archives so you don’t miss new episodes, which are released throughout the year.

Listeners, we need your help to make this podcast better! We need to know a bit more about you and what themes you’re interested in. You can share this information with us by visiting smartsurvey.co.uk/s/ontherecord, that’s smartsurvey.co.uk/s/ontherecord.

We’ll include that link in the episode description and on our website. You can also share your feedback or suggestions for future series by emailing us at OnTheRecord@nationalarchives.gov.uk.

Finally, thank you to all our experts who contributed to this episode. This episode was written, edited, and produced by Tash Walker and Adam Zmith of Aunt Nell, for The National Archives.

This podcast from The National Archives is Crown copyright. It is available for re-use under the terms of the Open Government Licence.

You’ll hear from us soon!

Records featured in this episode

-

- From our collection

- WORK 11/237

- Title

- House of Commons records on the arrangements of accommodation consequent on the admission of women.

- Date

- 1918-1930

-

- From our collection

- E 42/78

- Title

- Receipt by Ermejarda, or Ermegerda, late the wife of Henry de Sancto Mauro, for one mark

- Date

- Middle Ages

-

- From our collection

- PREM 13/2412

- Title

- Prime Minister's Office records on the strikes at Fords of Dagenham

- Date

- 1968

Further information

Record revealed

A letter by the women workers at Fords of Dagenham

A handwritten letter written by sewing machinists working at Dagenham car plant who famously went on strike for equal wages in the late 1960s.

Research Guide: Medieval and early modern family history

We introduce some of the major family history sources for the medieval (974-1485) and early modern (1485-1714) periods and tell you how to search for them.

Research Guide: London Metropolitan Police

This guide provides advice on how to find records (primarily staff records) of the London Metropolitan Police.

Subscribe to On the Record

pod.link

Find the podcast on your preferred service

On the Record is available wherever you get your podcasts.

Tell us what you think

smartsurvey.co.uk

Fill in our survey

Listeners, we need your help to make this podcast better! We need to know a bit more about you and what themes you’re interested in.

Copyright

If you wish to re-use any part of a podcast, please note that copyright in the podcasts and transcripts in some cases belongs to the speakers, not to the Crown.