I find myself feeling a huge weight of responsibility being a Writer in Residence here at The National Archives. Without sounding too pompous, I feel like the newest branch of a family tree in a great lineage of historical legacy. Myself, a 20-year-old writer in my third year of study at The Royal Central School Of Speech And Drama – a 121-year-old theatrical institution – on placement in a government agency established in 1838, holding documents dating back over a 1,000 years.

In my six weeks here, I've gained a newfound appreciation for this institution and the value of archiving state documents, preserving a nation’s memory for eternity. Now, at the end of my time here, I have embarked on the exciting challenge to craft, write and develop a 30-minute play based on my findings.

First impressions

I can confidently say my pre-conceived ideas of the Archives were instantly shattered and upended. There were no labyrinths of cobwebbed corridors, no rickety shelves and blankets of dust sat atop loose papers and artifacts, all hidden six feet underground with lock and key.

Instead, I have witnessed the remarkable work that is taking place in The National Archives’ Education and Outreach Team. They strive to make these documents accessible for the community, whether that be for families of young children, individuals in care-home environments and schools across the country, academics and researchers, GCSE students to those with PHDs. They use various immersive, sensory and other creative outlets to do this, often establishing a link between historical documents and drama, as I endeavoured to do.

One also can’t help but feel overwhelmed when they hear of the 14 million documents stored here, and the impossible prospect whittling down one story from 14 million.

Then one day, I stumbled across a name: Elvira Chaudoir, and that changed.

Who was Elvira?

Elvira Chaudoir was a Peruvian double agent operating in the midst of the Second World War. She had opulent taste in gambling, money and fashion, effortless wit and persuasiveness, and an incredibly smart way of thinking. To the Nazis, she was Agent Dorette, supposedly passing information from the Allied Forces to give the Nazis the upper hand. To MI5, she was Agent Bronx, selling the Germans nothing but misinformation, lies and deception to help win the war.

A photograph of Elvira Chaudoir, Agent Bronx, sent to Monica Sheriffe just before her she set off on her first coat-trailing mission in July, 1942. She writes: ‘to darling Monica, Elvira. July, 1942’.

Because of this duplicitous trust she had established with the Germans, Elvira became a crucial part of Operation Fortitude – now known as the D-Day Landings. She helped save the lives of thousands that day, and hundreds more over the course of the war. I stumbled upon her name in passing during the MI5: Official Secrets exhibition and discovered even more in The National Archives' story on her.

I was immediately struck by her character, her dry humour, her marvellous fashion sense, and above all, her bravery. Two questions then arose: why haven’t I heard of this extraordinary woman before, and how can I share her story?

Scene One: The Ritz, 1939

One of my first intentions with what was soon titled Elvira's Fabulation, was for the dramaturgy of the play – its structure and fabric – to be a character in itself: frivolous, farcical, whimsical and quite frankly chaotic. She doesn’t stay in one place for long and neither does the play, jumping from scene to scene, country to country, mission to mission. This is the story of a woman who ran away from her husband to seek expensive gambling affairs in Cannes, created false aliases to fool the Nazis, and hopscotched around Europe in a daring feat of espionage. A theatrical interpretation of her life must reflect that, but the most important element in all of this was her voice.

Finding Elvira's voice

Most of the documents that regard Elvira are correspondences between the men in her life who dictate judgement upon her. Through various telegrams and letters, she remains absent, but in the times when her own voice was documented, it dazzled.

I felt it absolutely necessary to incorporate her own words in the piece. Although the worlds created in my play are often fabricated, accentuated and satirised upon, her own words remained authentic, true and became the beating heart of the play.

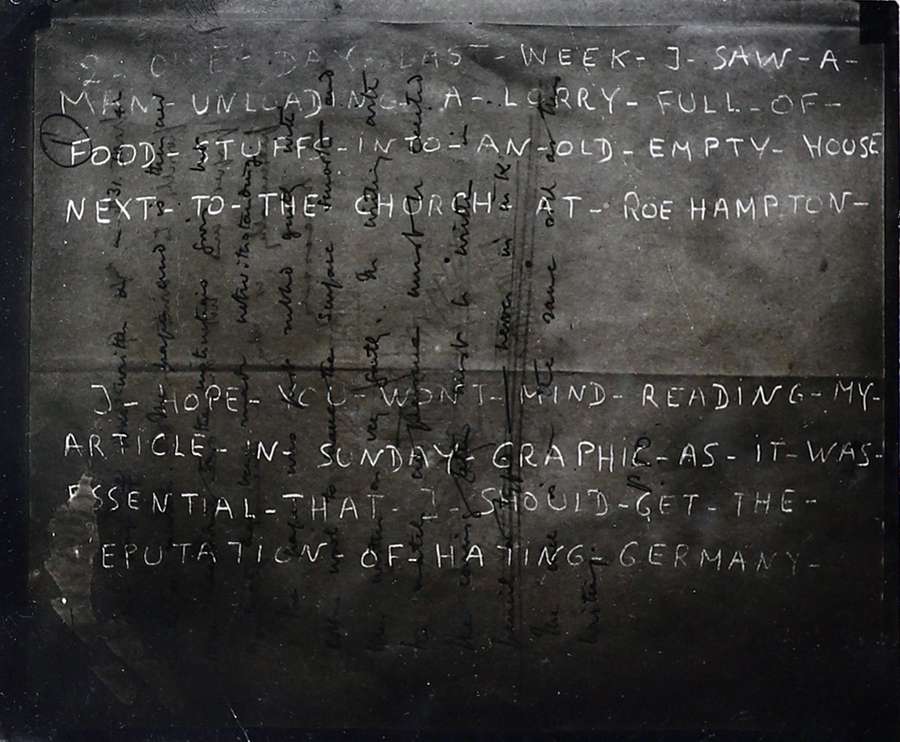

Most of her own words that are retained here are written in matchstick and lemon juice, more commonly known as invisible ink, an emblem for her work. Her story is palimpsest: an old document where the text has been removed and covered or replaced by new writing. The truth is hidden behind lies and manipulations. One must use tools to uncover the true meaning of her words, but I think it’s finally time for her story to be told, in visible ink. It’s time she stops hiding.

I hope you won't mind reading my article in Sunday Graphic as it was essential that I should get the reputation of hating Germany.

Elvira's coded letter with an apology to Helmut Bliel – a semi-official German intelligence (Abwehr) agent. Catalogue reference: KV 2/2098

The process

Upon researching her life, I found a lot of parallels between her and my time here in the Archives. In his book, Double Cross: The True Story of the D-Day Spies, Ben Macintyre shares a similar sentiment, and remarks that 'these agents fought exclusively with words and make-believe', and I feel I inhabit a similar role. Whilst I am not a secret double agent passing on enemy secrets across the border (although, I would say that, wouldn’t I?) I am creating and fabricating stories. I'm passing on intel to others, I am using words to inform, to educate, to share, albeit in a much less ministerial and top-secret capacity.

This has been an incredibly exciting opportunity. I have thoroughly enjoyed the process this piece has taken on; through of initial discovery, extensive research in The National Archives’ Reading Rooms, transposing her words into a theatrical context and the construction of the Elvira’s Fabulation. In a sense, the play acts as an archive in itself: a demonstration of Elvira Chaudoir’s life, her work, her impact and the legacy she holds in the 21st century.

The National Archives and I are hoping to stage a reading of Elvira’s Fabulation in 2026.

About the author

Rupert Shirley is a third-year undergraduate student studying Writing for Performance at the Royal Central School of Speech and Drama. He has just completed a six-week Writer in Residence module at The National Archives, as part of his studies.

The story of

The double agent who hid D-Day from the Nazis: Elvira Chaudoir

A life of charm, high-stakes, and duplicity saw Elvira Chaudoir play a cunning role in the Allied victory at D-Day.