Important information

This article includes descriptions of religious discrimination, including enslavement based on faith, archaic language towards the global majority and a graphic description of torture.

Two Moroccan cities

In 1603, civil war spread across Morocco. Its coastlines immediately became vulnerable to attack by European powers seeking to take advantage of the country’s instability. With threats from land and sea, few parts of Morocco flourished during this period.

However, records at The National Archives reveal that the twin cities of Rabat-Salé, located on the country’s Atlantic coast, not only endured but emerged as a dynamic force during these perilous times. An influx of people from overseas would transform Rabat-Salé from two small coastal settlements, into an independent state.

The story of how Rabat-Salé emerged also epitomises the decisive and active role that North African cities had in repelling European imperial expansion. At a time when empires had colonised vast territories in the Americas, would-be imperialists in Europe were increasingly looking to North Africa with similar intentions.

Yet, as the records we hold show, cities like Rabat-Salé sustained vibrant metropolitan and maritime cultures. The strength of North Africa’s coastal cities would shield the region from European imperialism until the French conquest of Algeria in 1830.

Moriscos and marauders

From the early 16th century, European states became increasingly intolerant of religious minorities within their borders. Some of the hundreds of thousands of people displaced by this religious strife would emigrate to North Africa, serving as agents of change. It was substantial migration from Europe, which drove the initial expansion of Rabat-Salé.

The most significant wave of migration came in 1609, after King Philip III of Spain ordered the descendants of Muslims (known as Moriscos) to leave his kingdom, expelling up to 500,000 people.

Across previous centuries in Iberia, Muslims and Jews had been forced to convert to Christianity following Christian conquests, but their descendants had continued to endure discrimination. This included the concept of limpieza de sangre (blood purity), which considered Moriscos' blood tainted by their religious ancestry and unfit for positions of power.

Expulsion from Spain left Moriscos with a hatred towards their former overlords, which they carried with them to North Africa and elsewhere.

The Agrevances they complain of are these ffolowinge

First as these men are thrust into senories & lyve as vassals to such as have over them both high & low Justice & at ther pleasure make them labor like slaves to which they pay darly over and above ther ordinarye tace (as vassals to them) the fyrste of all the fruits and commodytues they rayse, & in case any of these gent be in want or indebted any thowsants of crownes which is a usuall thinge they are bound as subjects & vassals to them, to pay yearly the interest of all such somes as ther masters owe & are indebted

They are forbidden to weare any kynd of weapon except a knyfe such be without poynt & only serve for the table and such like: the rest is defended upon payne of loose both of lyffe & goods

They are fforbydden to run within a myle of the sea siyd except it be ffollowinge their horsse or necessatye constrayne

By the Inquisition they are so miserably troubled & vexed that they burie yearlye of them, tow or three hondreth, for matters of small moment, especially wher any thinge is to be gotten

The kinge forceth them every yeare to paye him one hondreth and fyftye thousande crownes which is gathered amongest those which have family without acomptinge men unmaryed whereof are very manye...

A report of Morisco grievances in Spain, which includes that they were forbidden from carrying weapons, could not travel within a mile of the sea and were persistently monitored by the Spanish Inquisition, 1609. Catalogue reference: SP 94/16

A wealthy community of Moriscos from the town of Hornachos were among these refugees fleeing Spain. Taking their worldly possessions, around 3,000 of them made it to Morocco, moving port-to-port in search of a new home until they settled in the ruins of the fortress at Rabat. Thousands of other Morisco refugees, mostly from Andalusia, would follow in the coming years, building a new walled town outside the existing fortress.

Following the Moriscos’ arrival, others from further north began to make their way to Rabat-Salé. They arrived due to the end of Spain’s wars with England and the Netherlands, which left thousands of sailors unemployed. The Virginia colonist John Smith saw this demobilisation first-hand, noting that sailors were divided into those who had made a significant amount of money from raiding Spanish ships during wartime, and those ‘that were poore and had nothing but from hand to mouth, [who] turned Pirats’ according to his memoir The True Travels, Adventures, and Observations of Captain John Smith.

Like the Moriscos, these apparent pirates sought outposts where they could live undisturbed. A small number of them became established at Mamora (Mehdya today), just north of Rabat.

However, many English and Dutch sailors at Mamora behaved like their wars had never ended, freely attacking Spanish ships and then carrying the goods back to sell to local merchants. They quickly caught the attention of the Spanish navy, which attacked the city in 1614, capturing it for the crown of Spain.

The pirates that survived this attack made their way to Rabat, where they were cautiously welcomed by Moriscos who shared their animosity towards Spain.

... so was present at the taking of and this examinant and others of the company wer by force taken out of the said shippe by the said Stephenson into his man of warre and detained by him at sea about the space of six monthes and then turned into the roade of Mamora in Barbarye where he gott from the said Stephenson and wente ashore amoungst the moores, rather adventuring his fortunes with them than to continues with the piratte, And coming ashore he was taken by the moores and ymprisoned for that he would not surve them as a gonner, and after he had remayned prisoner there aboute foure or fyve months he took the advantage and stole away by nighte and gott onboard a Fflemish shipp of Horne whereof Cornelis Jahnsen was master, and had passage therein for England & was landed near Brighthelmston on the coast of Sussex & from there came to Ratcliff, & so wente to Charham & was there apprehended.

Being asked what shippe or goodes the said Captain Stephenson took at sea or in any harbour, while he was with him Sayth he took not any.

...

The deposition of Paul Goddard before the English High Court of Admiralty, while on trial for piracy. He witnessed a dispute over plunder at Mamora in which English pirates tortured a Dutch captain ‘burned his fingers endes off, & tormented him otherwise by the privy members’. Catalogue reference: HCA 1/47

A corsair state

The occupation of Mamora illustrates how Morocco’s internal strife made it vulnerable to foreign invasion. Without formal navies, coastal cities increasingly came to rely on corsairs (sailors who operated privately outfitted warships). These sailors would bring goods plundered from enemy ships and could serve as a makeshift defence force, should the need arise.

Accordingly, Rabat-Salé proved an ideal haven for corsairs. Moriscos from Hornachos had the capital to invest in ships, while Andalusian and European sailors were able and willing to serve as crew. Well crewed and armed, many corsairs would sail into the Strait of Gibraltar to capture Spanish ships, bringing their plunder back to sell in Rabat, which in turn drew merchants from northern Europe keen to purchase rich cargos taken from Spain’s vessels returning from the Americas.

A section of a map of north-western Africa from John Seller’s Atlas Maritimus, 1698. Rabat-Salé is visible on the right, just south of the Straits of Gibraltar, indicated as ‘Salee’. Catalogue reference: FO 925/4111

The corsairs also engaged in the faith-based system of enslavement that was common in the Mediterranean during this period. As Rabat-Salé was Islamic, its corsairs were permitted to capture Christian sailors and sell them into slavery, with those captured facing a life of unremitting toil. A similar system operated in the Christian Mediterranean, where thousands of Muslim captives were also sold and enslaved by corsairs. It is estimated that at least three and a half million people were enslaved in this system between 1450 and 1850.

En tenerifa en Caso de don Loúis éterriano - Hee hath slaves whose names are Mahamett a Byrocke Ally dayd Hyram Cras - Side Abdala wold know whether he were liveinge or not.

A brief note from the correspondence of the English merchant Robert Woodruffe, asking that he enquire after ‘Mahamett a Byrocke’, ‘Ally Daud’, and ‘Hyram Cras’, all Muslims enslaved at Tenerife, around 1632. Catalogue reference: HCA 30/841

In Morocco, the only formal means of emancipation was to pay a ransom or to convert to Islam, with many opting for the latter. Converts grew in number and were known as ‘renegades’ in Christian Europe.

For instance, when the Dutch sailor Jan Janszoon, a veteran of the Netherlands’ war with Spain, was taken by corsairs in 1618, he converted to Islam and adopted the name Mourad. He later relocated to Rabat and quickly achieved the title of reis (captain) before being elevated to the equivalent rank of admiral. His rise continued when he was granted the governorship of Rabat-Salé by Morocco Sultan Muley Zidan in 1624, after which the corsair population of the city expanded dramatically.

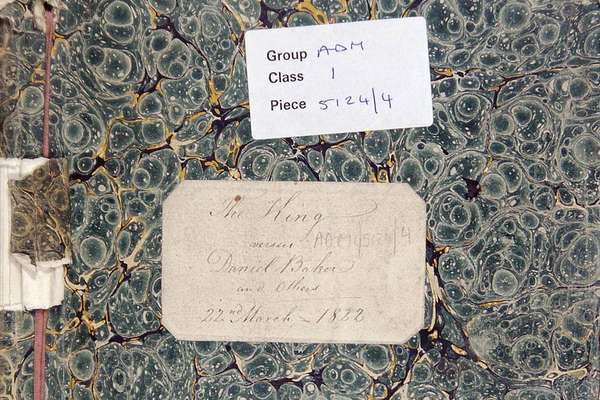

Charles I and Rabat-Salé

As governor, Mourad directed his raiders away from the vessels of his Dutch countrymen and towards English shipping instead. After the succession of Charles I as King of England in 1625, pressure built for the new monarch to respond to these attacks.

The same year, Charles dispatched his first envoy, John Harrison (1579–1656), to Morocco. Upon arrival Harrison penned a treatise to the king imploring him to sponsor the invasion of Morocco’s ports. Moriscos, he claimed, despised Catholicism and were oppressed by Islamic rulers throughout Morocco, so would willingly accept their conquerors and convert to Protestantism.

La relacion que Joan Arizon [John Harrison] criado de v.m. hizo de aver acomodado su venida de Tetuán a esta ciudad decele fue mui pequeño servicio para la obligación queio Y todos los de este reino tenemos describir a v.m. y meresce su nombre y grandeza y ansi le suplico me mande en todo quanto fuere de su real gusto y servicio y me huelgo mucho de la paz capitulada con los andaluses moradores desta fuerca Por ser en beneficio en beneficio y bien de los casallos de v.m. y en el de todos y en confirmación de lo que Antiguamente y siempre avia entre los dos reinos guarde dios nos perea v.m. y aumente de maiores Reinos desde Sobre cele [Salé] 2 de la luna de ramadan 1036 [17 May 1627]

The account that John Harrison, servant of Your Majesty, gave after arriving from Tetouan to this city was a very small service for the obligation I have. And all of us in this kingdom have a duty to Your Majesty, Your name and greatness, and so I beseech You to command me in all that is of Your royal pleasure and service. And I rejoice greatly in the peace accorded with the Andalusian inhabitants of this fortress, for it is for the benefit and good of Your Majesty's house and for all, and in confirmation of what formerly and always existed between the two kingdoms. May God protect Your Majesty and increase Your Kingdoms onward. [Salé] 2nd of the moon of Ramadan 1036 [May 17, 1627]

A letter purporting to be from an Andalusi morisco in Rabat-Salé, offering his service to Charles I. One of many documents sent to England by Harrison as he worked to expand English influence over the two cities, 1627. Catalogue reference: SP 102/2

However, Charles ignored Harrison, intending to take a more peaceful approach. In 1627, he successfully negotiated peace and the release of English captives from Rabat-Salé, but it was not to last.

In May 1631, the English captain John Maddock encountered a ship from Rabat off the southern coast of Portugal, manned by ‘moors [Moriscos] and renegathoes [renegades]’. The two ships fought, with Maddock eventually prevailing and taking the Rabati ship as a prize. He then continued his voyage to Cadiz in Spain, where he sold the Moriscos into slavery. When word reached Rabat-Salé of these events, its Diwan (ruling council) deemed the peace violated and the city’s corsairs had free reign to target English ships again.

That to the peace between his Majestie and Sallie mentioned in their petition and the great number of his Majesties Sujects redeemed from thence by virtue of that peace his is a mere stranger, But confesseth that in the month of May 1631 he the said Wye was merchante of parte of the Ladinge of pipestaves of the ship the William and John od London then bound for Cales [Cadiz] and St Lucars [San Lucar] and at that time and in that voyage John Maddocke mentioned in the said petition was master and Commander of the said shipp the William and John and upon the Eleventh daie of the said month of May aforesaid the said Shipp the William and John prosiquting [prosecuting] her said voyage about six leagues of the Southward Cape a vessel Spanish built burthen about 60tie tonnes manned with Moores and other Renegathoes to the number in all of between 50tie and 60tie men came upp with the said Shipp the William and John and conceiving her to bee a Collier (as the Companie of the said man of warre confessed) made divers greate shott at her intendinge thereby to take her, but by force of the ordinance of the William and John and the mistake of the Companie of the man of warre conceavinge the William and John to be a Straights ship (as they afterwardes with such relucatancie confessed

A response to a petition by Mary Farre, whose husband was seized and sold into slavery at Rabat-Salé in response to Maddock’s actions. In this response, a sailor from his ship maintains that they acted in self defence, around 1632. Catalogue reference: HCA 30/849

As reports of renewed attacks reached Charles I, his diplomatic efforts floundered. Pressure continued and in England, sensational stories of English captives in Morocco proliferated. Accordingly, in 1637 he decided to act, dispatching six ships to attack Rabat-Salé under William Rainsborough, who, upon arrival, found the two cities in open war with one another. In this chaos, the English fleet was able to blockade the mouth of the Bou Regreg River that separated the cities, forcing the Moriscos to surrender. Yet, peace lasted less than a year. As England slid into its own civil war, Rabat-Salé’s corsairs would continue to target English vessels, now with little retaliation.

An urban model

Other cities in North Africa shared the urban model of Rabat-Salé. Coastal settlements accepted people of all kinds from overseas, making their populations drastically different from regions inland. Often, they were autonomous or semi-autonomous, relying heavily on trade and corsairing.

Additionally, back-and-forth diplomacy and responses to grievances saw wars with many different powers come and go, allowing corsairs to switch targets. This adaptability made such cities formidable and, as in the case of Charles I, made foreign rulers hesitant to invade and keen to pursue diplomacy instead.

As for its legacy, Rabat-Salé exemplifies how North African coastal cities not only adapted to changes in overseas exchange but also resisted imperial expansion, using a distinctive blend of inter-cultural collaboration, diplomacy, and predatory maritime strategies.