Early life

Born in 1721 in St James’s, London, John was half-brother to the novelists Henry and Sarah Fielding. Nothing is known of his education and very little of his life before 1749, although John may have served in the Royal Navy. Suffering from poor eyesight, he was blinded in 1740 after what he called an ‘accident’, but which was in fact negligent treatment by a surgeon. He was awarded £500 of damages for the incident in 1741.

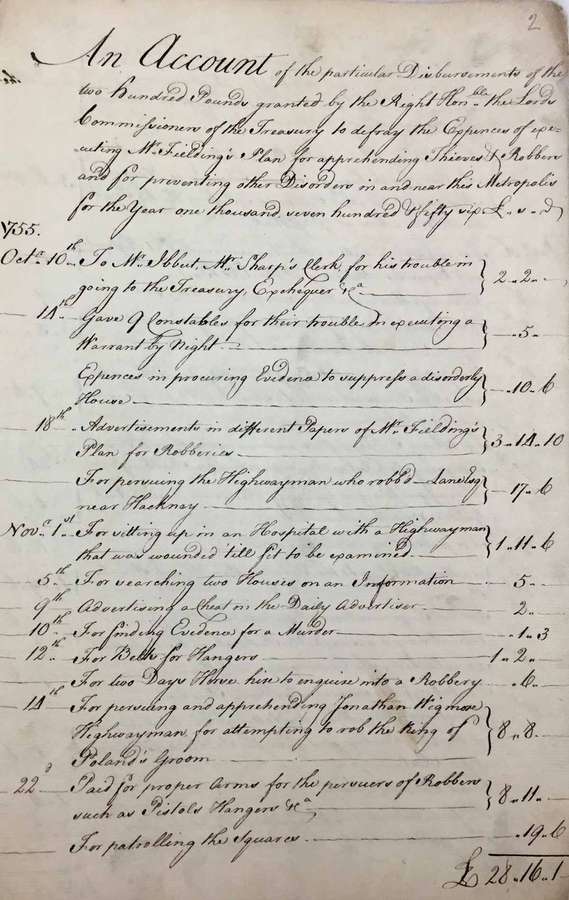

An account of the particular Disbursements of the two hundred pounds granted by the Right Hon...ble the Lord Commissioners of the Treasury to defray the Expences of executing Mr Fielding's Plan for apprehending Thieves & Robbers and for preventing other Disorders in and near this Metropolis for the year one thousand seven hundred & fifty six.

Account book of John Fielding, including payment of £8 6s for apprehending highwayman Jonathan Wigmore for attempting to rob the groom of Stanislaus I, the exiled King of Poland, 1756. Catalogue reference: T 38/671

A calling to fight crime

John would not let his blindness hold back his career, and together with his brother Henry, who was also a successful playwright and lawyer, set out to fight the crime that was rampant upon the streets of London.

By the early 1750s the crime rate in the capital had soared. The War of Austrian Succession had ended with the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1748, and left many soldiers and mariners unemployed and turning to crime. This caused the existing parish law enforcement process to be overwhelmed and increasingly reliant on ineffective (and mostly aged) nightwatchmen, and highly fraudulent ‘thief-takers’, bounty hunters usually paid by the victims of an offence. Henry had written a satirical play about one in 1743 entitled The Life and Death of Jonathan Wild, the Great, about the villainous ‘Thief-Taker General’ Jonathan Wild, who had been hanged at Tyburn in 1725.

The Fielding brothers would form Britain’s first voluntary policing service, the plain-clothed Bow Street Runners, in 1749 (with the help of the High Constable of Holborn, Saunders Welch). On becoming Henry’s personal assistant in 1750, John helped him root out corruption and improve the competence of those engaged in administering justice in London. The Bow Street Flying Squad was essentially the first organised police force, and through the regular circulation of a police gazette in 1772 (originally called The Quarterly Pursuit), which contained descriptions of known criminals, John Fielding established the basis for the first criminal records department.

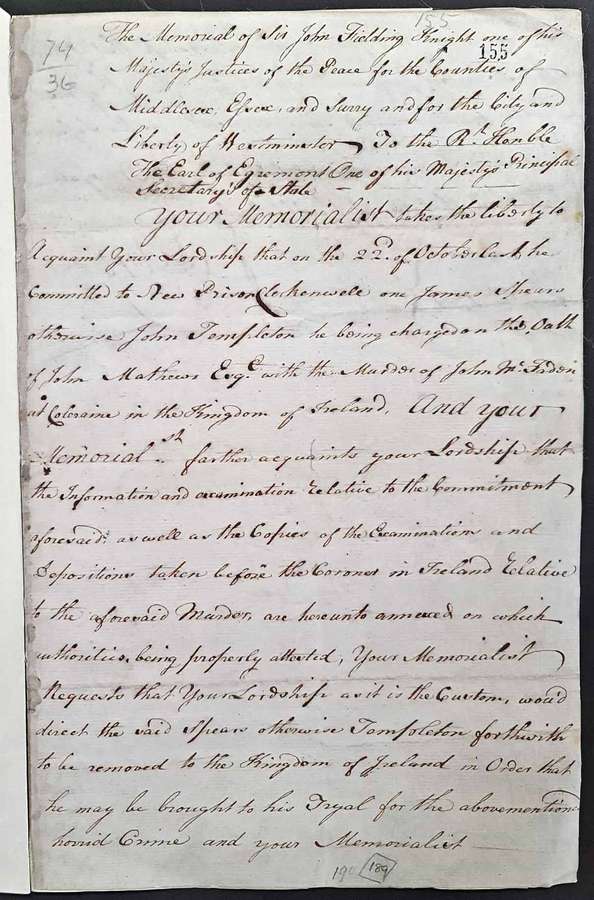

The Memorial of Sir John Fielding Knight of His Majesty’s Justice of the Peace for the Counties of Middlesex, Essex, and Surrey and for the Liberty of Westminster. To the Right Honourable the Earl of Egremont one of..[the]..Principal Secretary’s of State.

Your Memorialist takes the Liberty to acquaint your Lordship that on the 22nd October last year he committed to New Prison Clerkenwell one James Speers [Spears] otherwise John Templeton he being charged on the oath of John Mathews with the murder of John McFaden at Coleraine in the Kingdom of Ireland, and your Memorialist farther acquaints your Lordship that the information and examination relative to the containment aforesaid as well as the copies of the Examination and depositions taken before the Coroner in Ireland relative to the aforesaid murder are hereby announced…

Your Memorialist Requests that Your Lordship…would direct the said Speers otherwise Templeton forthwith to be removed…to Ireland in order that he may be brought to his Tryal for the above mentioned horrid Crime…

Memorial [petition] of Sir John Fielding requesting that James Speers be removed from the New Clerkenwell prison to Ireland to stand trial for the murder of John McFadden at Coleraine, 19 November 1761. Catalogue reference: SP 37/1/17, ff 155–156

When Henry Fielding died in 1754, John was appointed magistrate at Bow Street, Covent Garden in his place. He became renowned as the eminent ‘Blind Beak of Bow Street’ (‘beak’ being a common slang name for people in authority). John is said to have recognised 3,000 criminals by their voices alone, relying on his heightened senses of sound and touch. He also introduced a new system in which crimes could be reported in newspapers, which he hoped would encourage witnesses to come forward.

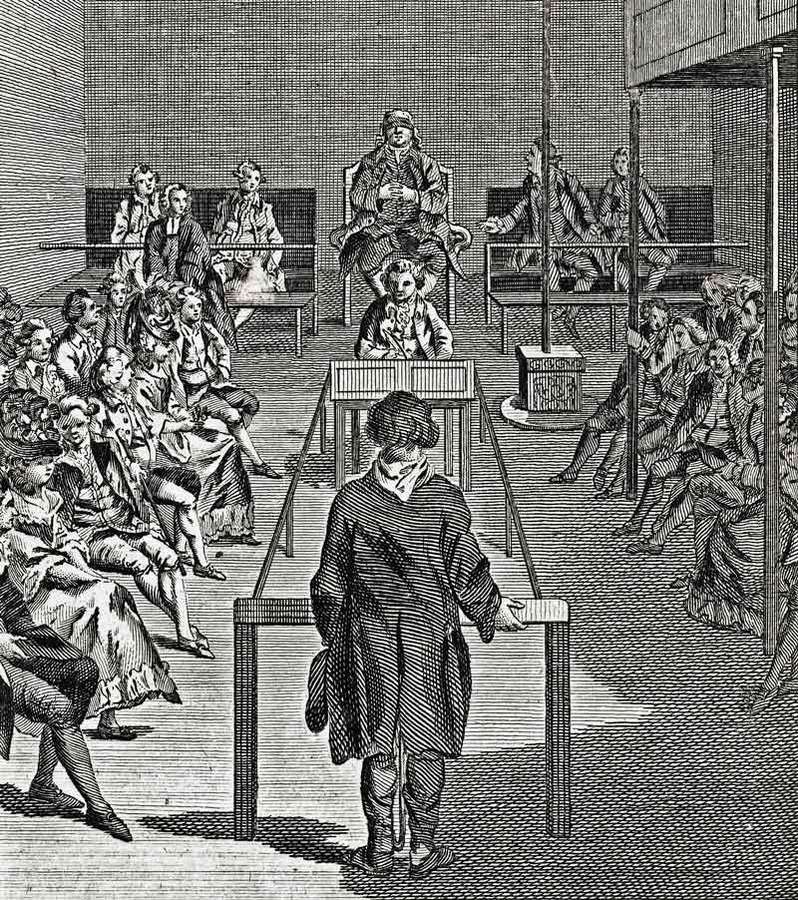

John Fielding presiding over a trial at the Public Office, Bow Street. From The New and Complete Newgate Calendar by William Jackson, 1795.

In 1763, with short-lived government funding, John raised the Bow Street Horse Patrol to combat highway robbery, which had seen an unprecedented surge after the demobilization that followed the ending of the Seven Years’ War. The noted antiquarian and Inspector of Imports and Exports, Horace Walpole, had himself been robbed by highwaymen in Hyde Park in November 1749, and areas like Hounslow Heath and Enfield Chase were notorious for highway robbery. Fielding's Patrols were ready to arrest any prowling highwayman or unmounted footpad who fell into their net.

Having broken up most of the gangs of street robbers – such as the well-to-do ‘Mohocks’ who terrorised the Strand, and the vicious Armstrong gang who were finally overcome in 1755 – and protecting the roads leading into the capital, John set up a system of rapid communication and published listings of stolen goods.

Significant successes

John was criticised by a Committee of the House of Lords for a lack of vigour in quelling riots by the Spitalfields silk weavers, and by supporters of the radical MP for Middlesex John Wilkes (who became Lord Mayor of London in 1774, and whom George III referred to as 'That Devil Wilkes') at electoral hustings in the later 1760s. Nevertheless, he was knighted in 1761 for his already considerable services to law and order.

His major achievement lay in the General Prevention Plan of 1772, which aimed to deter potential offenders by the ‘Certainty of speedy detection through the drawing of all informations of fraud and felony into one point,’ his Bow Street ‘Public Office’ headquarters.

Chairing the 1770 Committee on Burglaries and Robberies, John was also responsible for legislating the 1774 Westminster parishes Night Watch Act, which set minimum standards in terms of the number of watchmen, their pay, and their basic duties. Although he became Magistrate for the counties of Middlesex, Essex, and Surrey, John's authority was extended to all corners of the British Isles.

Ultimately John Fielding's greatest successes were in securing the arrest of the pro-American dockyard arsonist John the Painter in February 1777, who threatened to bring terror in the name of the Patriot cause upon Plymouth, Bristol and Portsmouth at the height of the Revolutionary War, and in his measures to defend London during the infamous anti-Catholic Gordon Riots of June 1780. Those riots saw both Newgate Prison and the Bank of England attacked, during four days in which London was ruled by the mob.

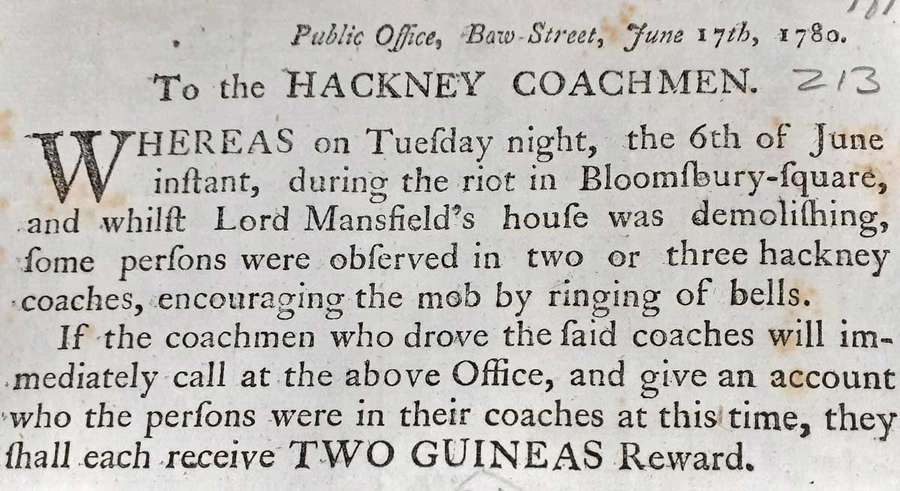

Public Office, Bow Street, June 17th, 1780.

To the HACKNEY COACHMEN.

WHEREAS on Tuesday night, the 6th of June instant, during the riot in Bloomsbury-Square, and whilst Lord Mansfield's house was demolishing, some persons were observed in two or three hackney coaches, encouraging the mob by ringing of bells.

If the coachmen who drove the said coaches will immediately call at the above Office, and give an account who the persons were in their coaches at this time, they shall each receive TWO GUINEAS Reward.

Reward offered by Sir John Fielding for information against Hackney Coachmen for their involvement in the destruction of Lord Mansfield’s house during the Gordon Riots, 17 June 1780. Catalogue reference: SP 37/14/101, f.213

Mercy and patronage

While acting under the conventions of the eighteenth century ‘Bloody Codes’ of criminal justice, John was severe with hardened criminals and responsible for sending many men and women to the gallows. However, he could be merciful, and was lenient with the young, especially first-time offenders.

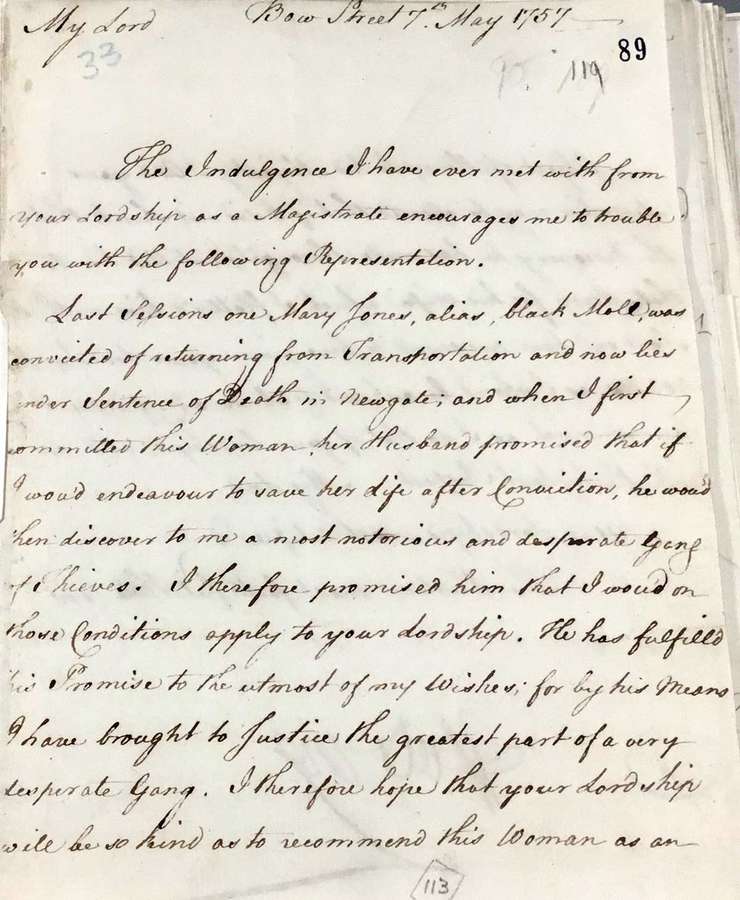

Bow Street 7th May 1757

My Lord

The indulgence I have ever met with from your Lordship as a Magistrate encourages me to trouble you with the following Representation.

Last sessions one Mary Jones, alias, black Moll, was convicted of returning from Transportation and now lies under sentence of Death in Newgate; and when I first committed this Woman, her Husband promised that if I would endeavour to save her life after Conviction, he would then discover to me a most notorious and desperate Gang of Thieves. I therefore promised him that I would on those conditions apply to your Lordship. He has fulfilled his Promise to the utmost of my Wishes; for by his means I have brought to Justice the greatest part of a very desperate Gang. I therefore hope that your Lordship will be so kind as to recommend this Woman as an...

John Fielding at Bow Street asking that Mary Jones [sent to Newgate for pickpocketing] be recommended for mercy, 7 May 1757. Catalogue reference: SP 36/137/1, ff 89-90

Having a genuine concern for the poor and public health, he petitioned for both the lowering of the price of basic foodstuffs, and for affordable medicines. Like William Hogarth, Fielding regarded the drinking of beer as a wholesome alternative to gin (as shown, for example, in this note).

John organised charities to feed and clothe abandoned children, and institutions to teach them reading, writing and to acquire a trade. He helped to found the Marine Society in 1756 for recruitment into the navy, and a seminary in 1769 for seafarers to equip boys for the Merchant Service (now known as the Merchant Navy).

As governor of Magdalen Hospital, he was also a life-governor of the Orphan Asylum for Deserted Girls (established in 1758), which later became the Royal Female Orphanage. John was also a member of the progressive Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce.

A long-term legacy

Although blind, John Fielding enjoyed reasonable health, and held the post of Chief Magistrate at Bow Street for twenty-five years, ultimately earning £400 and a knighthood. While assisting his more famous brother and serving as an officer of the law, he reformed the justice system and helped lay the foundations for Robert Peel’s Metropolitan Police Act in 1829, and the creation of a nationwide standing police force.

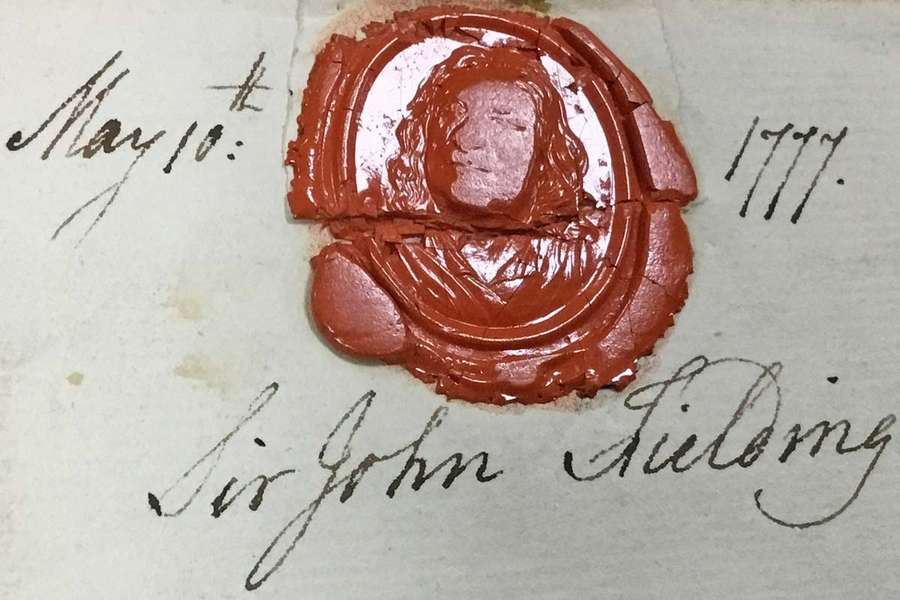

John Fielding's seal, 10 May 1777. Catalogue reference: SP 37/12/30, f.63

Becoming ill in early 1780, John died at Brompton Place on 4 September 1780, at the time the Gordon rioters destroyed the records he had gathered so meticulously at his Bow Street office. He was buried at All Saints Church, Chelsea.

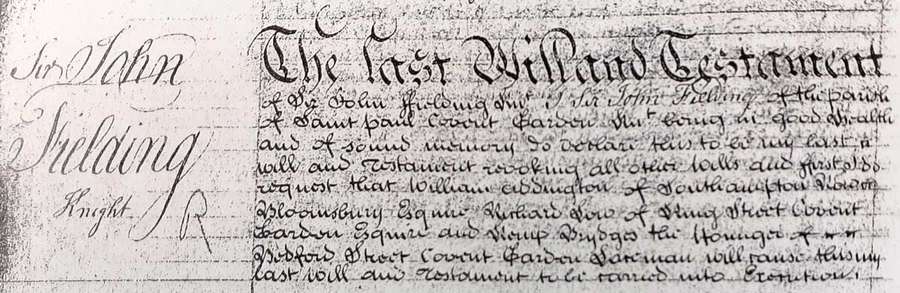

Sir John Fielding's 'Last Will and Testament', 3 November 1780. Catalogue reference: PROB 11/1071/28

Further reading on Sir John Fielding

Ciara Griffith, Sir John Fielding (2015).

Elaine A. Reynolds, ‘Sir John Fielding, Sir Charles Whitworth, and the Westminster Night Watch Act, 1770–1775’, in Louis A. Knafla, ed., Policing and War in Europe, Criminal Justice History Vol. 16, London, 2005.

Patrick Pringle, Hugh & Cry: The Birth of the British Police (London, 1955).

Philip Rawlings, Fielding, Sir John (2004).

R. Leslie-Melville, The Life of Sir John Fielding (1934).