Record revealed

Letters from the curator of St Vincent Botanic Gardens

The writings of botanist George Caley show surprising connections between Britain’s colonial past and some of our favourite festive spices.

Important information

This article briefly mentions enslaved persons and their forced labour.

Images

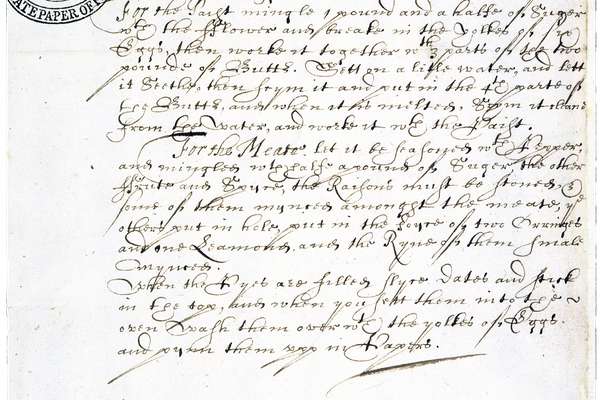

Image 1 of 3

Minutes of the Royal Horticultural Society in London meeting where Caley’s Caribbean cloves were presented. Catalogue reference: WO 43/150/269

Partial transcript

‘Minute relative to the cloves. Sent from St Vincents by Mr George Caley C.M.H.S. formerly exhibited to the Society and referred, for examination, by the Council, to Solomon Israel Esq F.H.S.

At the meeting of the Society on the sixth of June, fifty specimens of Cloves, and two of mace, prepared in different ways were exhibited, accompanied by a list, and the particulars of the plans which had been adopted in the preparation, drawn up by George Caley, Superintendent of the Botanic Gardens at St Vincents, and a corresponding member of the Society.

Mr Caley’s object in transmitting the specimens to the Society was, to have an opinion as to their respective merits, in comparison with those imported from the East Indies, and the Council being desirous of affecting him every assistance in their power, referred the whole to Solomon Israel Esq. F.H.S. whose long experience as a spice merchant eminently qualified him to pronounce upon their merits. Previous to stating Mr Israel’s observations upon the different specimens, it will be necessary, briefly to notice the modes of preparing the cloves in the islands of the Indian Archipelago. This may be done with considerable accuracy partly from the information communicated by Mr Israel, and partly from John Crawfurd’s interesting History of that part of the world, lately published.

Image 2 of 3

The results of the examination of clove specimens by members of the Royal Horticultural Society. Catalogue reference: WO 43/150/270

Partial transcript

The result of the examination appears to be that by adopting the same mode as that pursued by the cultivators in Amboyna [Ambon Island], both Cloves and Mace may be grown and ripened in as high perfection at St Vincents, as in the East.

Image 3 of 3

Letter from George Caley to William Merry (Deputy Secretary of War), May 29, 1822. Catalogue reference: WO 43/150/273

Partial transcript

I wrote to [Sir Ralph Woodford, Governor of Trinidad] last year, informing him, I would furnish him with twenty thousand clove berries, if he would prepare a piece of ground for them, but to this proposal I received no answer until the season was nearly over. If it is the intention of Government, that an Establishment of this nature should be kept up in the West Indies, and propagate the spices, perhaps, the Secretary of War is not aware, that by giving this garden proper protection, a thing by no means difficult to a public spirited Governor, it is capable of doing more in one year, than the garden in Trinidad can do in twenty to come.

Why this record matters

- Date

- 1821–1824

- Catalogue reference

- WO 43/150

In 1821, the St Vincent Botanic Gardens were at risk of closing. The curator in charge, botanist George Caley, wrote a series of letters to the War and Colonial Office protesting this decision. Now stored at The National Archives, they offer insights into the role of colonial botanic gardens in the early 19th century, and the movement of plants around the British Empire.

The St Vincent Botanic Gardens were the first botanic gardens in the Caribbean, established in 1765, just two years after St Vincent became a British colony. The gardens became part of a global network transferring botanical knowledge and profitable medicinal, ornamental, and edible plants from the colonies to Britain. This was made possible due to the forced labour of enslaved people living in St Vincent. By the early 19th century, the St Vincent gardens were home to significant plants including the ‘only two bearing nutmeg trees in the West Indies’.

However, Caley had a difficult relationship with his superiors in the Colonial Office, who decided to stop financially supporting the gardens in 1822.

Before leaving his post, Caley was asked to organise the relocation of the botanical gardens’ plants, including fully grown trees, to the botanic gardens in Trinidad. However, he believed this was impossible, stating, ‘As to the removal of the plants, with the exception of a few […] I might as well pretend to remove a forest.’

Within this correspondence about the closure of the gardens, there are also records documenting Caley’s interaction with the Royal Horticultural Society (RHS) in London. From this, we can learn that he sent samples of cloves to the RHS in the early 1820s and ‘at the meeting of the Society on the sixth of June, fifty specimens of Cloves, and two of mace, prepared in different ways were exhibited’.

Caley wanted the opinion of the Society’s members on ‘their respective merits, in comparison with those imported from the East Indies’. Native to the Maluku Islands in Indonesia, cloves are the flowering buds of the tree Syzygium aromaticum.

Like many valuable spices, including nutmeg, trade in cloves was dominated by the Dutch East India Company. This was until French botanist Pierre Poivre smuggled seeds out of their native islands in the late 18th century, which led to wider availability. British colonial officials later planted the clove tree in the St Vincent Botanic Gardens, and these records show the movement of its clove specimens to London.

This festive spice is now commonplace in Britain's autumnal and Christmas recipes, from sweet mincemeat to pumpkin spice. Cloves are also, famously, pressed into oranges at wintertime to make pomanders – balls of fragrance that make a room smell fresh.

These records are one example of the colonial origins of many of the food histories recorded in our collections. It also highlights the far-reaching impact Britain’s colonial activities still have on everyday life.

The St Vincent Botanic Gardens were reinvigorated later in the 19th century during the peak of colonial botanical activities and remain open to tourists today.

Featured articles

Record revealed

A recipe for six mince pies 'of an indifferent biggnesse'

This 17th-century mince pie recipe contains spices, eggs and raisins, but also something slightly stranger.