Background

Emmeline Pankhurst was the leader of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), one of the predominant suffrage organisations involved in campaigning for votes for women. She interacted constantly with the government, which leaves us with a wealth of records around her involvement in the movement for women’s suffrage.

Emmeline Pankhurst, 1908. Catalogue reference: COPY 1/526 46322.

Our records contain everything from prison petitions in Emmeline’s own words asking for suffragettes to be treated as political prisoners, as well as items seized from WSPU headquarters. They provide fascinating insights into her activities and life.

Votes for women

The Women’s Social and Political Union

The WSPU had been founded in 1903 in Manchester, determined to try to get votes for women by any means necessary. Founded by Emmeline and her daughters, the organisation was frustrated by the many prior decades of slow progress and disappointments. The WSPU was known for its militant actions: its members became known as ‘suffragettes’ – a Daily Mail slur that was reclaimed by the movement. The National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) was the predominant constitutional organisation, often known as the ‘suffragists’.

The general office at the WSPU headquarters, Lincoln’s Inn House, Kingsway. As seen in the Illustrated London News. Catalogue reference: ZPER 34/142.

Emmeline was not a flawless character; along with daughter Christabel, she had a reputation for being authoritarian. Under her leadership the WSPU was highly organised; from its headquarters in central London it communicated with regional branches, organised militant campaigns and reached out to members. The state closely monitored activities at the headquarters, keeping a particularly close watch on Emmeline.

‘Deeds, not words’

The WSPU’s policy of direct action had begun in 1905, when Christabel Pankhurst, daughter of Emmeline, and Annie Kenney interrupted a meeting to ask politicians whether they were in favour of votes for women. In the following years the methods and tactics developed, often organically, as the women repeatedly felt their voices were not being listened to. Emmeline herself was arrested, and evaded capture, many times for the cause.

‘For nearly 50 years we had your sympathy and your support, and nothing happened ... Nothing can stop militancy now, and it is going on until we get the vote. We tried by constitutional ways to get you to give us the vote, but you did not do it. What can we do now but carry on this fight ourselves? And I want you, not to see these as isolated acts of hysterical women, but to see that it is being carried out on a plan and that it is being carried out with a definite intention and a purpose. It can only be stopped in one way: that is by giving us the vote.’

Emmeline Pankhurst speaking at Hampstead Town Hall, 14 February 1913, as recorded in a police report

Record revealed

List of suffragettes arrested from 1906–1914

More than a thousand people who supported women’s right to vote were arrested for their activism. This document records them – and includes some famous names.

As the movement continued, mass window smashing campaigns and the targeting of MPs’ houses became more common forms of protest for the WSPU.

Militant methods were often divisive. While historians disagree about their effectiveness, our records show the huge impact militant actions had across government.

Extract from The Illustrated London News © ‘From pavement-chalking to arson, window-breaking and bombing: the progress of Militant Suffragism’, 24 May 1913. Catalogue reference: ZPER 34/142.

Foot soldiers of the movement

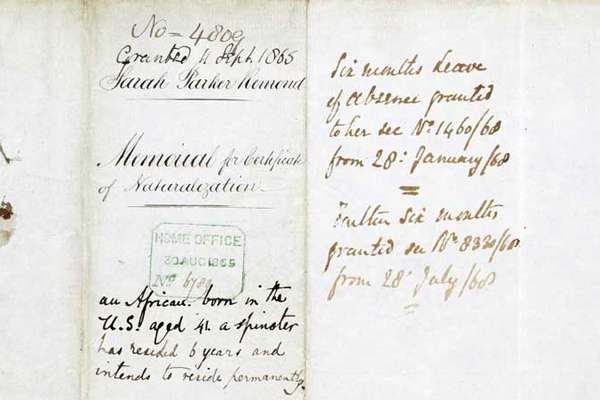

While it is great to celebrate figureheads, such as the Pankhursts, the strength of the suffrage movement lay in the foot soldiers who were willing to fight alongside them. The Home Office Amnesty from 1914 records 1,224 women and 108 men who were imprisoned between 1906 and 1914 for offences committed for the votes for women campaign.

These numbers only reflect those arrested, not the people who avoided arrest or campaigned constitutionally; they represent the tip of the iceberg of the movement and the records we hold.

This was clearly a national, mass, organised movement.

Suffragettes Annie Kenny and Christabel Pankhurst 1906. Catalogue reference: COPY 1/494.

The Representation of the People Act

At the outbreak of war, Emmeline paused the militant movement, and instead worked with the government to support the war effort. Many suffrage supporters took up roles on the home front or travelled abroad to support the war.

Eventually, after decades of peaceful and militant campaigns, on 6 February 1918, the Representation of the People Act (1918) received Royal Assent and came into force. This act provided some women with a vote in Parliamentary elections for the first time.

Representation of the People Act, 1918.

AN ACT

TO

Amend the law with respect to Parliamentary and Local Government Franchises, and the Registration of Parliamentary and Local Government Electors, and the conduct of elections, and to provide for the Redistribution of Seats at Parliamentary Elections, and for other purposes connected therewith.

Chapter 64. 6th February 1918.

Representation of the People Act, 1918. Catalogue reference: C 65/6385.

-

- From our collection

- C 65/6385

- Title

- Representation of the People Act, 1918

- Date

- 1918

Ten years later in July 1928, the Conservative government’s Representation of the People Act (1928) finally extended the vote to all women over 21 years of age. Emmeline had died just weeks before this, on Thursday 14 June 1928. Millicent Fawcett, the leader of the NUWSS, was still alive and attended the parliamentary session to see the vote take place.

Emmeline was commemorated two years later with a statue in London’s Victoria Tower Gardens. It was unveiled in 1930 by the Prime Minister, Stanley Baldwin, who had opposed votes for women.