In this episode, host Chloe Lee is joined by Will Butler, a specialist in British society during the First and Second World Wars, to explore what that first VE Day was like, from the soldiers and medics who’d been at the frontline, to the folks at home who wanted peace — and for butter to be easily available again in British towns and cities.

Listen to the episode

Listen

Victory in Europe Day (VE Day)

Audio transcript for "Victory in Europe Day (VE Day)"

Chloe Lee: On Tuesday, May 8th, 1945, the Allies who had been fighting the Second World War formally accepted Germany’s unconditional surrender. May 8th became known as Victory in Europe Day, or VE Day, and is still marked every year.

I want to hear what that first VE Day was like, from the soldiers and medics who’d been at the frontline, to the folks at home who wanted peace — and for butter to be easily available again in British towns and cities.

I'm Chloe Lee, a record specialist at The National Archives. I also host our podcast On the Record at The National Archives, uncovering the past through stories of everyday people.

In our earlier episode, The Second World War: Legacies, Language and Diaspora, I heard about the global scale of the war. Victory in Europe, when it finally came, looked very different depending on where you were in the world. For people in France, it meant freedom from tyranny; but for eastern Europe, when the war receded it left far greater uncertainty in its wake.

In this episode I want to learn what documents and testimonies can tell us about what VE Day meant to people in Britain, and beyond.

To guide me is Will Butler, a specialist in British society during the First and Second World Wars and the history of the British Army. Welcome, Will!

Will Butler: Hi Chloe. Thank you very much for having me.

Chloe: So Will in 1918 Armistice Day, it came very quickly concluding the First World War. What had the government learned from that? And how did that inform plans for VE day in 1945?

Will: So on the 11th of November 1918 the armistice is signed. And really, you know, certainly for the people at home, and even to some extent, the people fighting on the front lines, it came as quite a surprise. You know, a real shock. Came out of the blue, really. There was no kind of lead up to it. There was no obvious signs that the kind of Allied forces at this point were going to collapse. And so what you kind of experience and what you get, certainly at home and particularly in London, on that day in 1918 is this enormous outpouring of emotion, of celebration, perhaps a little too celebratory as well.

Certainly, the authorities viewed it that way, particularly In London, a lot of the reports talk about huge gatherings of people, and in so doing, there is a lot of drunkenness and a lot of things like vandalism, so and again, you know, it's primarily these reports are interested in crime. You know, that's what they're interested in. But they really talk about how those celebrations went a little bit too far for many so you know, and particularly the number of, yeah, kind of the drunkenness is a key part to all of that.

The war had been going on for six years. Again, naturally, there was going to be some relief and a release of this kind of tension of fear in a slightly different way. You know, the war was slightly different in 1918, by 1945 particularly, again, the UK had experienced aerial bombardment in a way that it hadn't experienced in 1918 so there were different experiences from that point of view. But you know, certainly in the planning for Victory in Europe, or as it was referred to for a long time, ‘Ceasefire Day’. You know this, this idea of Victory in Europe Day, doesn't come about, actually, until quite late on.

Chloe: I’ve never heard of that ceasefire day.

Will: Yeah, absolutely and that's, that's how it's referred to. And they start talking about this Ceasefire Day as early as October 1944 so well over six to nine months before VE day itself. And it's partly because they're keen to plan that, keen to see what it might look like when war comes to an end, and obviously at that early stage and even through March and April 1945 they don't really know what the end of the war in Europe is going to look like. Is it going to be an unconditional surrender? (Which is what happens in May ‘45). Is it going to be a gradual wearing down of the armed forces, where you know the war would still be kind of going on in some respect? So that they're not really sure, and they're kind of tackling that and dealing with that for a long time until it starts to become clear. And obviously those negotiations, and there are negotiations for the German surrender, which start to take place in that first week of May 1945. And you know, as a result, they can start to put in place some of these plans that they've been discussing all of this time. And you know, as you might expect, there's lots of discussions around how government departments should act again, there's the Ceasefire Handbook, which is produced in March 1945 for government departments instructing them on exactly what they should be and shouldn't be doing once it becomes clear that the war is coming to an end, and that's particularly around communication and war production. You know what things need to change? What things need to stay the same? And you know, they're discussing a lot of these, these kinds of issues. And again, even within that book, in March 1945 they're still not quite sure what the end of the war is going to look like.

Chloe: Interesting. And so how did that unfold? How did those officials use propaganda to try and control public reaction and manage expectations, as they were kind of more and more sure of that surrender?

Will: So obviously you know, throughout the whole war, there's an enormous propaganda effort, both to get behind the war effort itself, you know…

Chloe: And abroad

Will: Both home and abroad, you know, trying to convince various populations, various audiences, of the necessity and the need to carry on fighting in that context, but there's also an enormous amount of censorship which goes on. There's a lot of control of the news and of information.

Chloe: And I imagine that's quite a contrast to the First World War, the kind of way that information was controlled.

Will: So again, really, what the, you know, the various government agencies do is learn a lot from the First World War, where there is still, you know, and that's really the advent, really, of that propaganda machine is, kind of occurs during the First World War. And, you know, and certainly the British authorities. But also, you know, different nations learn a lot from those experiences. So they're really able to control information, newspapers and the radio, the two main (the wireless in that context), these are the two main ways in which people can get their information. And again, if we're thinking about the home front, it's the various national newspapers, which are heavily controlled in terms of what they can and can't report about the war. And you know that people are getting, then their information from the BBC, ultimately, and again, there's an element of censorship which goes on there, and that's really important, you know.

Essentially, though there is censorship, it's very clear that the war is going in the right direction for the Allies for quite a long time. Certainly, after D DAY in June 1944 there were small setbacks around the kind of winter of 1944/45 but then once we get into the spring of 1945 it becomes increasingly clear that the war is slowly coming to an end in Europe. So although they're controlling information. It's clear, you know, even to the civilian population and certainly, the military population and the military authorities that things are going in the right direction, and the end of the war is in sight, just when was really the question?

Chloe: I mean, despite the celebrations in Europe, though, when that does happen and that information is released, I'm aware that the war is still going on in Southeast Asia. How did the government acknowledge those who were still under Japanese occupation?

Will: So that was that was a really important issue for the government to deal with. So they recognise that at home and in mainland Europe there, there's going to be a demand, a want, a need, almost to celebrate the end of the war in Europe, but they're acutely aware that the war in Southeast Asia, the war against Japan, was still going to be ongoing beyond May 1945. Again there are lots of discussions about how that might affect both the military who are fighting in Southeast Asia, but also in particular, the civilian population who might still be under Japanese occupation as well, or were held as civilian internees or prisoners of war by the Japanese. So they're acutely aware, and there are, certainly, when peace is announced, one of the first things that happens is Winston Churchill, as British Prime Minister, composes a telegram to be conveyed to that population under occupation, which really talks about the need to continue the fight.

Chloe: Will do you have that telegram? Can we hear a bit from it?

Will: Of course, so that there's a really interesting passage which kind of summarises exactly the kind of message that the authorities are trying to convey. So it says:

“After a gigantic struggle of nearly six years, war has ceased in Europe and all the millions of her people who were enslaved have been liberated from the foul Nazi domination. This means that the time for your liberation also is at hand and it is of you that we are thinking on this day. The armed might of the British Commonwealth and America with their Allies against Japan is now free to strike with tremendous and undivided power”.

So there are kind of two things going on there. It's like, you know, we're celebrating in Europe, but we are, you know, we haven't forgotten you. We're still thinking of you. And now this enormous struggle has happened in Europe, this enormous fight we can read, you know, divert all of our resources to come to your liberation.

Chloe: It’s really interesting to think about how that would have been received. Yeah, if you're in a camp and you hear that message, are you going to feel are you going to feel much more empowered, or are you going to feel really kind of disappointed at the fact that across the world, people are celebrating peace?

Will: Yes, you know absolutely. And even you know for the military, who are still fighting this war as well, you know for them, they're still in danger. You know, in that way, in a similar way to those under occupation. And of course, you might not, even if you're under Japanese occupation, you might not have even received the difficulty of actually conveying and sending that information and ensuring that as many people as possible are aware.

Chloe: Can we assume that messages would have got through to those people? That kind of information?

Will: Yes, certainly, you know, information about the end of the war would have been available, and the possibility of it for most.

Chloe: So knowing all of that, then was there actually debate about whether celebrations were appropriate while fighting continued?

Will: Absolutely there were. So there were, there were debates in the House of Lords, for example, about, you know, particularly the appropriateness of any celebrations. And again, there are a couple of reasons for that. So there's the, you know, making sure that those still fighting the war didn't feel forgotten away from Europe. You know, that kind of aspect to it. But there's also a practical element to it. If these celebrations happen in Europe, if there's a bank holiday, if everyone… munitions workers get a day off, what does that do for war production and the ability for the allies to continue fighting in Japan? Does it further delay the end of the war in Southeast Asia? So you know that you have that kind of multi-faceted debate, which isn't just about, you know, ensuring that those still fighting are forgotten, but there's, you know, the kind of serious, practical considerations of, well, if we celebrate this too much, will people think that the war is done, you know, it's done with and we can now relax, and we don't have to focus our efforts on winning the war in Southeast Asia.

Chloe: Yeah. And so what impact then, did the European victory have on war production, as you've mentioned, and the military's ongoing efforts?

Will: So as I say, you know that probably you know, it is a minor impact. And obviously, when the authorities are weighing this up, they're also quite pragmatic about it. They realise that people are going to celebrate this anyway. You know, even if there's no kind of official framework to this, of course, there's going to be relief. Of course, there's going to be excitement and happiness that the war is over. And primarily because, again, you know, populations on the home front, they've been subject to bombing, they've been subject to this real danger for so long, and though to some extent that had subsided By the spring of 1945 you know, there's a relief there that that danger is also over.

Chloe: And I assume also that knowledge that people's families might be returning and be reunited?

Will: Absolutely, however, of course, there's still that small uncertainty, you know, for those in Europe and for those fighting forces in Europe, well, where is my next step? Is my next step to be sent to fight against the Japanese?

Chloe: Okay, so how did VE Day celebrations differ between mainland Europe and Britain?

Will: So obviously, the end of the war in Europe meant different things to different people, depending on who you were, where you're from, and you know, obviously your experience of experiences of the war as well. So you know, for British people, for those at home in particular, you know it meant the end, the end of the threat and aero bombardment and all of those kinds of things that came with an active war against another European power. But obviously you have enormous numbers of the European population, people from France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Poland, and Italy, for example, who have very different experiences. And the end of the war means lots of different things. Depending on where you're from. So, you know, for French and Belgian and those from Belgium and the Netherlands, it meant, it really meant liberation from, you know, from Nazi oppression. In that context, for those from Poland and many 1000s of whom had settled at least temporarily. At that stage in the UK, during the war, there was a lot more uncertainty. What would the future look like?

Chloe: Is this home going to be the same? Am I going to want to return? There is Britain my new home? How do I feel about that?

Will: Exactly, exactly. So, you know, it doesn't mean this kind of feeling of relief and liberation. What it is actually a feeling of uncertainty and anxiety about, yeah, what is the world going to look like for them.

Chloe: Thinking about that, the Imperial War Museum holds an extraordinary account from Eric Lord, who was serving in the British Army in Cuxhaven in Germany, when liberation came. Let's listen to a clip of Eric's memory about the day peace came.

[AUDIO CLIP: ERIC LORD]

“It was a beautiful evening. I don't remember. I sat down on the grassy, grassy stretch of the aerodrome at Cuxhaven and tried to collect my thoughts.

And all I could think of was as that's the end of that. We don't anymore. We don't have to dig sit trenches and hear the sounds, that awful sound of the nebelwerfer. Therefore, the multi barrel mortar were no more, when we hear the shells screeching over, and yet, there should have been a great sense of relief. But we should have really, we should really have somebody to organise something. We should have all gathered round, raised our mugs and said, Here's to the PBI. Here's to the poor bloody infantry. Yes, that's what we should have done.”

Chloe: What I'm getting from that will is just a great sense of anti climax. Can you tell me a bit more about this nebelwerfer?

Will: Absolutely. So it's essentially, it's a rocket launcher, and it made this unbearably high pitched noise. You know, it's a horrible, horrifying, you know, screeching sound. And you know, really what he's talking about there is essentially not being under the threat of bombardment again. And, you know, it's really interesting hearing that testimony, and kind of thinking again about the end of the First World War, again in 1918 and you know, lots of soldiers on the front line in that context talk about all of a sudden at 11am on the 11th of November, there's silence. They can hear the birds, you know, all of those kinds of things. And there's, I think there's a similar thing here, that that immediate threat of danger, you know that danger immediately passes, but also a sense of okay. Now, what you know, as you say, that anticlimactic experience again, you know his focus, the soldiers around him, those on the home front, their focus for the last six years has been on defeat, defeating Nazi Germany. That's what the focus and that's what all the propaganda is talking about as well. And all of a sudden that happens. And so what? What next?

Chloe: Yeah, you just sit down. And then there's also this idea of celebration deferred, like we should have done this. It's so interesting how, when you remember something, you think, oh, we should have done that. And, and he talks about that.

Will: And to a large extent, they weren't able to do a lot of that celebration as well. So, you know, in his context, he is in Germany, you know, again, all of a sudden, the armed forces are then having to deal with tens, hundreds of thousands of soldiers, former enemy, though, that they have to disarm, you know. And again, the authorities are very aware of that, you know, there are communications which kind of say, you know, you know, they can there can be some celebration, there can be church services, entertainment, but we can't give any more rations for this activity. So there's still a very clear sense that there's a job to do. So there's kind of the reality there, and then the other reality really is tens, hundreds of thousands of refugees that the armed forces are dealing with, and particularly in the context, you know, so Bergen Belsen concentration camp had recently been liberated in the middle of April by British forces. So that obviously brings the stark reality of the war, you know, very close to home, you know, in a British context as well. And. But that brings home the serious nature, the real serious nature of the war and actually also the brutality of that period as well, and that's difficult to deal with. And how do you balance those emotions when you're dealing on a day to day basis with these really quite challenging situations.

Chloe: Tense fighting situations, you might have witnessed some really terrible things. You might have been part of that liberation group going into Bergen Belsen, and been told that law is over.

Will: And of course, you know, for a period of time you're doing something very different. You've been taught to fight. You've, you've, you've been instructed to kill. You know, ultimately, that's what you you know as kind of, you know, a member of the armed forces. That's what your objective is. And then all of a sudden, you're not dealing with that. You're actually dealing with care. You know, you're having to look after, you're having to…

Chloe: Administer all of those people that suddenly might be in your care or, yeah, I didn't even think about the sheer administration that goes into that process, not just if you're a soldier, but if you're also someone who's been displaced.

So we've heard directly from Eric there. But do any records in our collection reflect that align with that.

Will: I think absolutely, the records reflect the anti climactic nature of the end of the war. So you know, key collection are the war diaries, which exist for this period. And V Day barely gets a mention in those diaries.

Chloe: So interesting that, because, you know, often we're looking for something in the records. But this is something that we know is receiving lots of attention, taking lots of labour, and then, actually, it's what's missing in the war diaries.

Will: Absolutely, but what is there is, well, this is the job that we're doing. We're guarding this, or we're sending troops from here to here. You know, that's what you find in the war diary, and that they are very practical. That's why they exist. Is for that. But VE Day certainly barely gets a mention.

Chloe: So if we return briefly to London, how did the Metropolitan Police plan for VE Day celebrations? You mentioned drunkenness on the streets in 1918.

Will: So that doesn't happen in 1945 so and again, a lot of attention is given. And the records reflect the kind of planning for these celebrations, the drafting in of extra people. And that, in itself, is interesting. There are people still working on VE Day, you know this, this, again, there's still a job to do. There's not everyone that's celebrating, but the experience is very different. You don't have the drunkenness, you don't have reports of crime. The word kind of jollification is used in a lot of the reports about the feeling amongst the crowds. It's relief, it's thankfulness. They use these kinds of words a lot in the reports. And I think that is a really interesting observation in terms of how those crowds feel and what, you know, what they're doing and going through. And there are tens of thousands of people, you know, at least 50/60,000 people gather at Trafalgar Square and along The Mall and outside Buckingham Palace. But you know, and again, obviously, the Metropolitan Police reports are focused a bit on crime, you know, that's what they're interested in. That's the focus of the record, exactly. And there's barely any reports of any kind of crime or drunkenness. For the latter, it's partly because there isn't much beer in London so people physically can't drink too much. But, you know, but they talk about the attitudes of the crowd, they make those comparisons to 1918 as well, which is a really interesting observation that you know, they're very clearly aware that there's some similarities there, or the potential to be similarities. But the reports specifically, and they are asked to report specifically on how the crowds compare.

Chloe: Interesting, because it reminds me of the morale reports that we discussed in the previous episodes, and it's almost like the Met Police here are taking a morale report of people on VE day.

Will: Absolutely, and again, they're doing that in lots of different ways, on the home front throughout the war as well. You know the authorities are doing that, not just for the armed forces, but, but they are doing that at home as well. So it's a, it's really a continuation of that.

Chloe: And across empire and Commonwealth.

Will: Absolutely, absolutely that. So, you know, and as I say, the spirits are friendly and high. As I say, they use jollification a lot in in these reports, they say that, you know, people don't even attempt to go home. They sleep in the streets. They sleep in the parks. And that's fine, and that the celebrations go on for a number of days. It's not just that first day, it's two or three days. You know, people are gathering to hear speeches from the Prime Minister. They're gathering to hear speeches from the king. But that the atmosphere is pleasant, it's relief.

Chloe: The classic image I have of VE Day is neighbours celebrating in their streets with each other. The Imperial War Museum's oral history collection contains one woman's experience of this. She's called Audrey Parsons, and let's hear from her now:

"Shortcroft dissected [bisected] to what we call blocks in those days. And so we were invited to everybody's street party, but we had one of our own. And my because my mother could play the piano, she was popular all of them. And so we all had bonfires in the street. I mean, it melted the road, but we didn't care. We'd gone through enough melting of roads, and we brought the piano, which was really my grandfather's piano down the road to me, thought we were going to put it on the - My mother played the piano while I sang and danced. You know? It was great. And then we were invited to one at the other end of the road, which was Goldsmith Lane, and one at the other end of the road, which I think was Scudamoor Lane, and I'm sure it was only because my mother could play the piano, but they were great times. I mean, you had really good parties. This was VE Day, not VJ Day, because VJ Day came later. So most of the parties and the celebrations were for VE Day."

Chloe: You really get a sense of that jollification in more of a local sense, right? Well, how do these personal accounts compare with the official reports that we have?

Will: So obviously, the official reports aren't necessarily as colourful as some of those descriptions in into kind of painting that picture, but they broadly fall in line. Again, even the reports talk about just how much bunting there was for example.

Chloe: We don't have a measurement of bunting, and it's our stats you can share with us.

Will: Yeah. I mean, I'm not sure where all of the bunting came from, of course. Again, you know restrictions in wartime supplies. But they, the reports, talk about a lot of bunting, and they talk about tea parties. They talk about parties for children as well. Because, you know, again, another important aspect.

Chloe: I can't imagine, they would have had lots of fun food, though, at those children's parties.

Will: No absolutely not. So, you know, rationing is still very much part of daily life. So you know, they are their street parties. They're gatherings more than anything else, really. And Audrey spoke about bonfires in that context. And again, that was an enormous hallmark of a lot of the celebrations across the UK. Are these enormous bonfires. And again, you know, you have populations who have been in blackout conditions for a long time. They've not been allowed to, you know, have they haven't been street lights. They haven't been, there hasn't been this light. And, you know, this is a really interesting expression of that liberation from wartime restrictions, really. And you do get, again, in a lot of reports talking about the use of bonfires and the lighting of bonfires in all sorts of places as well.

Chloe: I mean that image of the police noting bonfires being lit out in bombed out streets. What does this image tell us about the complex emotions of VE Day?

Will: So again, as I said, these are gatherings. This is an event and an experience which hasn't necessarily been able to take place for a number of years. So there's that kind of reclaiming, that independence and that authority to be able to actually gather with people and in a positive way as well. But also, as you say, you know, bonfires being lit on bombed out streets. It's kind of also reclaiming space, in a sense, as well. You know, there's a real kind of symbolism there, whether consciously or not, that. They're using these spaces which contain, you know, stories of their own, and quite tragic stories of their own in a lot of contexts, to to use them as a means for celebration I guess.

Chloe: I didn't see it as that kind of defiant use of space. I mean, also, it's just making me think about people's experiences of grief, and if you know that moment allows people and gives space for them to grieve.

Will: Absolutely and reflect on that grief as well.

Chloe: So thinking through that, why do you think will that we have this kind of Home Front narrative of the day, the kind of bunting celebrations in the streets, that's what dominates our memory, rather than the experiences of soldiers and refugees.

Will: In some ways, it's a more positive story to tell. It's an easier story to tell. It's kind of less complicated in that sense that you know, again, this moment is a moment of celebration, and that's, you know, much more straightforward. Narrative is, you know, and naturally so, because that is also the dominant memory, potentially for a lot, particularly on the home front, is, you know, the memory is of the end of the war, and that feeling of relief and that kind of dominates your own memory, then of and when you reflect on your war experiences as well, you know. And, of course, you know, from that point of view, it's also less traumatic. And, you talk about, kind of reflecting on grief, actually, it's reclaiming that, almost not reflecting on grief, in some respects, because you're, you're thinking about the positive. And the end of the war and again if you think about the archive, archival evidence of this, it's dominated by press cuttings of those celebrations, of those crowds, those images. That's what photographers are taking photos of. They're taking images of these enormous crowds.

Chloe: We almost have these like image touchstones, these visual kind of touch points where we can think through those things.

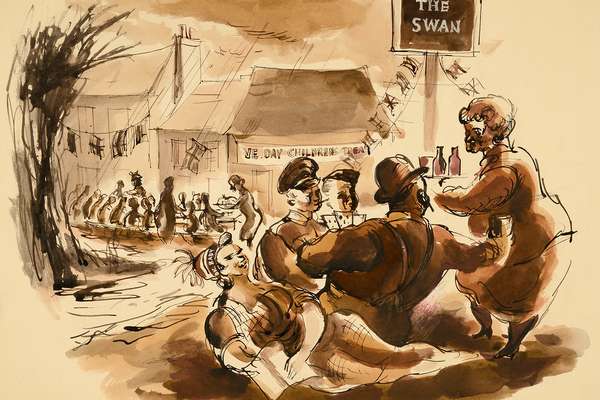

Will: Absolutely. And you know, we have a fantastic watercolour in our collection here as well, which is of a street party. And again, you know that very dominant memory and way of thinking about the end of the war. It's a watercolour to village scene. It's a kind of nostalgic scene of an English village having a street party for children and that's often how we think about it, and it's also, then often how the commemoration has taken place thereafter. You know, my own personal memory, my first memory of VE Day was the 50th anniversary in 1995 and that's exactly what I think of. Is the bunting is the street party. The 75th anniversary was similar, you know, and again, you know, the archive kind of shows us that when it reflects, you know, when these celebrations reflect on the armed forces, for example, where it's a little more problematic challenging to reflect on some of these more difficult experiences, you know, again, you know, you see commemoration being done in a particular way. And again, you see that in the archival record, it's, you know, parades and concerts and you know, kind of military music in that context. Because, again, that's, that's also a little more straightforward to, you know, it's entertainment, but it's also a little more straightforward to communicate as a means, perhaps.

Chloe: We are more increasingly aware of the psychological impact of the war.

So Will, I'm trying to imagine what I would feel like in 1945 and particularly how I feel about the future. I'm thinking about a nation wondering now…what? After years of total war.

Will: Absolutely and, you know, we talked about government propaganda, persuading people to continue fighting during the war. And one of the key aspects of that was the British government setting out what the future might look like, painting that picture, what, what might it look like in terms of social reform, or what might it look like, in terms of what the British Empire looks like, and a lot of that propaganda in particular focuses on things like self determination, for nations so obviously kind of feeding into, you know, those wartime experiences and then the decolonization which occurs in that kind of immediate war aftermath. But, you know, they're also looking at, as I say, things like social care and what health might look like, and what the government might do for its population. So all of that has been fed through both the home and fighting fronts as a means to, you know, persuade people to continue that fight, and that's what people are interested in. That's what they're looking to in that context. But there are realities in all of that as well, you know, and the world very quickly changes in 1945 there are the realities of that immediate, you know, liberation of concentration camps. For example, the last survivor of Bergen Belsen doesn't leave the camp and the medical services there until 1950 you know. And that's very stark. It shows the very stark reality of what the authorities are having to deal with. They're rebuilding Germany, which, by this point as well, in those first five years after the war becomes is split, and we have the kind of onset of the Cold War. And what I mentioned earlier around this uncertainty for Polish people in the UK, for example, and what the future might look for them. You know, that looks, again, very different to some of those messages that have been conveyed to the British population about what their future might look like as well.

Chloe: So we've talked a bit about our own understanding and memory of the Day commemorations. How have they evolved over the decades, according to the archive?

Will: So again, you know, as with our archival material, we have a lot of planning around what events and commemoration might look like, and they come in a variety of formats. You know, obviously the kind of paper archive, but also the increasingly the digital archive, particularly looking at the anniversaries, particularly around VE Day from the last 20 years, even in some respects, the commemorations themselves don't look hugely different. Again, there are lots of street parties, as I mentioned, you know, in that kind of celebratory element around the end of the Second World War in Europe. And that's, you know, an important aspect. You know, we haven't talked about victory in Japan VJ Day, which is interesting in itself. You know, thinking about how we remember the end of the Second World War, we potentially automatically think about the eighth of May, 1945 not the middle of August 1945 so that in itself, is quite interesting and telling. And again, to some extent, the archival record also reflects that as well. So obviously they have changed the way in which we commemorate in the last 80 years, but not a huge amount.

Chloe: I’m just thinking about that idea of silence that does continue through that we had in Eric's testimony. So will where else can people find more information and analysis of VE Day from us?

Will: So we've put together a highlights gallery of some of the key documents relating to VE Day. We've also written a piece about the liberation of Bergen Belsen as well, for anyone interested in that aspect of the end of the Second World War as well.

Chloe: Thank you so much for joining me today.

Will: Thank you.

Chloe: You can find those pieces that Will mentioned on our website.

Thanks for listening to On The Record from The National Archives. To find out more about The National Archives, follow the link from the episode description in your podcast listening app. Visit nationalarchives.gov.uk. to subscribe to On the Record at The National Archives so you don’t miss new episodes, which are released throughout the year.

Listeners, we need your help to make this podcast better! We need to know a bit more about you and what themes you’re interested in. You can share this information with us by visiting smartsurvey.co.uk/ontherecord, that’s smartsurvey.co.uk/ontherecord.

We’ll include that link in the episode description and on our website. You can also share your feedback or suggestions for future series by emailing us at OnTheRecord@nationalarchives.gov.uk.

Thanks to the Imperial War Museum for the audio clips, which are copyright IWM.

This episode was written, edited, and produced by Tash Walker and Adam Zmith of Aunt Nell, for The National Archives.

This podcast from The National Archives is Crown copyright. It is available for re-use under the terms of the Open Government Licence.

You’ll hear from us soon!

Records featured in this episode

-

- From our collection

- MEPO 2/6266

- Title

- Metropolitan Police reports on VE Day celebrations

- Date

- 1945

-

- From our collection

- HO 45/23203

- Title

- Home Office records on VE Day celebrations

- Date

- 1945

Allied Expeditionary Force, North West Europe (British Element): War Diaries

This series of war diaries contains the daily record of events, reports on operations, intelligence summaries, etc, of Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Forces and of Headquarters Formation and Unit Commanders.

Further information

In pictures

VE Day, 8 May 1945

Explore a selection of records from our collection relating to VE Day.

Research Guide: British Army operations in the Second World War

This guide will help you find records at The National Archives relating to military operations in the Second World War, including details of battles, invasions, secret operations and the daily activities of army units.

Subscribe to On the Record

pod.link

Find the podcast on your preferred service

On the Record is available wherever you get your podcasts.

Tell us what you think

smartsurvey.co.uk

Fill in our survey

Listeners, we need your help to make this podcast better! We need to know a bit more about you and what themes you’re interested in

Copyright

If you wish to re-use any part of a podcast, please note that copyright in the podcasts and transcripts in some cases belongs to the speakers, not to the Crown.