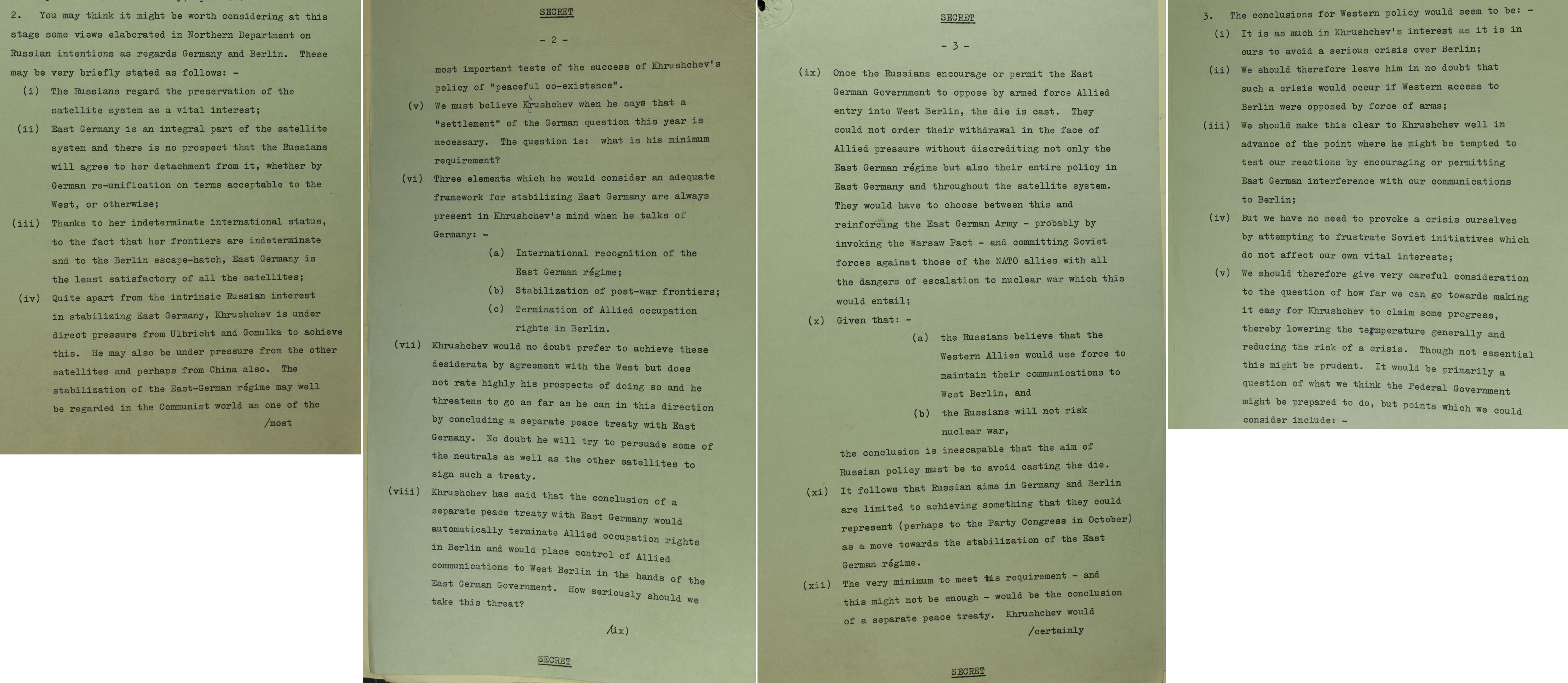

Foreign Office document analysing Soviet leader Khrushchev’s attitude to Germany and Berlin, April 1961. (Catalogue ref: FO 371/160534)

Transcript

…

- You may think it might be worth considering at this stage some views elaborated in Northern Department on Russian intentions as regards Germany and Berlin. These may be very briefly stated as follows:

- The Russians regard the preservation of the satellite system as a vital interest;

- East Germany is an integral part of the satellite system and there is no prospect that the Russians will agree to her detachment from it, whether by German re-unification on terms acceptable to the West, or otherwise;

- Thanks to her indeterminate international status, to the fact that her frontiers are indeterminate and to the Berlin escape-hatch, East Germany is the least satisfactory of all the satellites;

- Quite apart from the intrinsic Russian interest in stabilizing East Germany, Khrushchev is under direct pressure from Ulbricht and Gomulka to achieve this. He may also be under pressure from the other satellites and perhaps from China also. The stabilization of the East-German regime may well be regarded in the Communist world as one of the most important tests of the success of Khrushchev’s policy of ‘peaceful co-existence’.

- We must believe Khrushchev when he says that a ‘settlement’ of the German question this year is necessary. The question is: what is his minimum requirement?

- Three elements which he would consider an adequate framework for stabilising East Germany are always present in Khrushchev’s mind when he talks of Germany:

- International recognition of the East German regime;

- Stabilisation of post-war frontiers;

- Termination of Allied occupation rights in Berlin

- Khrushchev would no doubt prefer to achieve these desiderata [desired wishes] by agreement with the West but does not rate highly his prospects of doing so and he threatens to go as far as he can in this direction by concluding a separate peace treaty with East Germany. No doubt he will try to persuade some of the neutrals as well as the other satellites to sign a treaty.

- Khrushchev has said that the conclusion of a separate peace treaty with East Germany would automatically terminate Allied occupation rights in Berlin and would place control of Allied communications to West Berlin in the hands of the East German Government. How seriously should we take this threat?

- Once the Russians encourage or permit the East German Government to oppose an armed force Allied entry into West Berlin, the die is cast. They could not order their withdrawal in the face of Allied pressure without discrediting not only the East Germ regime but also their entire policy in East Germany and throughout the satellite system. They would have to choose between this and reinforcing the East German Army- probably by invoking the Warsaw pact- and committing Soviet forces against those of the NATO allies with all the dangers of escalation to nuclear war which this would entail:

- Given that:-

- The Russians believe that the Western Allies would use force to maintain their communications to West Berlin. And

- The Russians will not risk nuclear war,

The conclusion is inescapable that the aim of Russian policy must be to avoid casting the die.

- It follows that Russian aims in Germany and Berlin are limited to achieving something that they could represent (perhaps to the Party Congress in October) as a move towards the stabilization of the East German regime.

- The very minimum to meet this requirement-and this might be enough-would be the conclusion of a separate peace treaty.

…

- The conclusions for Western policy would seem to be-:

(i) It is as much in Khrushchev’s interest as it is in ours to avoid a serious crisis over Berlin;

(ii) We should therefore leave him in no doubt that such a crisis would occur if Western access to Berlin were opposed by force of arms;

(iii) We should make it clear to Khrushchev well in advance of the point where he might be tempted to test our reactions by encouraging or permitting East German interference with our communications to Berlin;

(iv) But we have no need to provoke a crisis ourselves by attempting to frustrate Soviet initiatives which do not affect our own vital interests;

(v) We should therefore give very careful consideration to the question of how far we can go towards making it easy for Khrushchev to claim some progress, thereby lowering the temperature generally and reducing the risk of a crisis. Though not essential this might be prudent. It would be primarily a question of what we think the Federal Government might be prepared to do…