Policing pigeons

Prior to the First World War, keeping pigeons was a popular and seemingly harmless hobby. But the outbreak of conflict in 1914 brought suspicion over their uses: the Home Office believed that carrier or homing pigeons owned by ‘enemy aliens’ were being used to send messages to the continent. The MP Sir Frederick Handel Booth said: ‘An alien enemy with a racing pigeon is far more dangerous than one with a live bomb.’

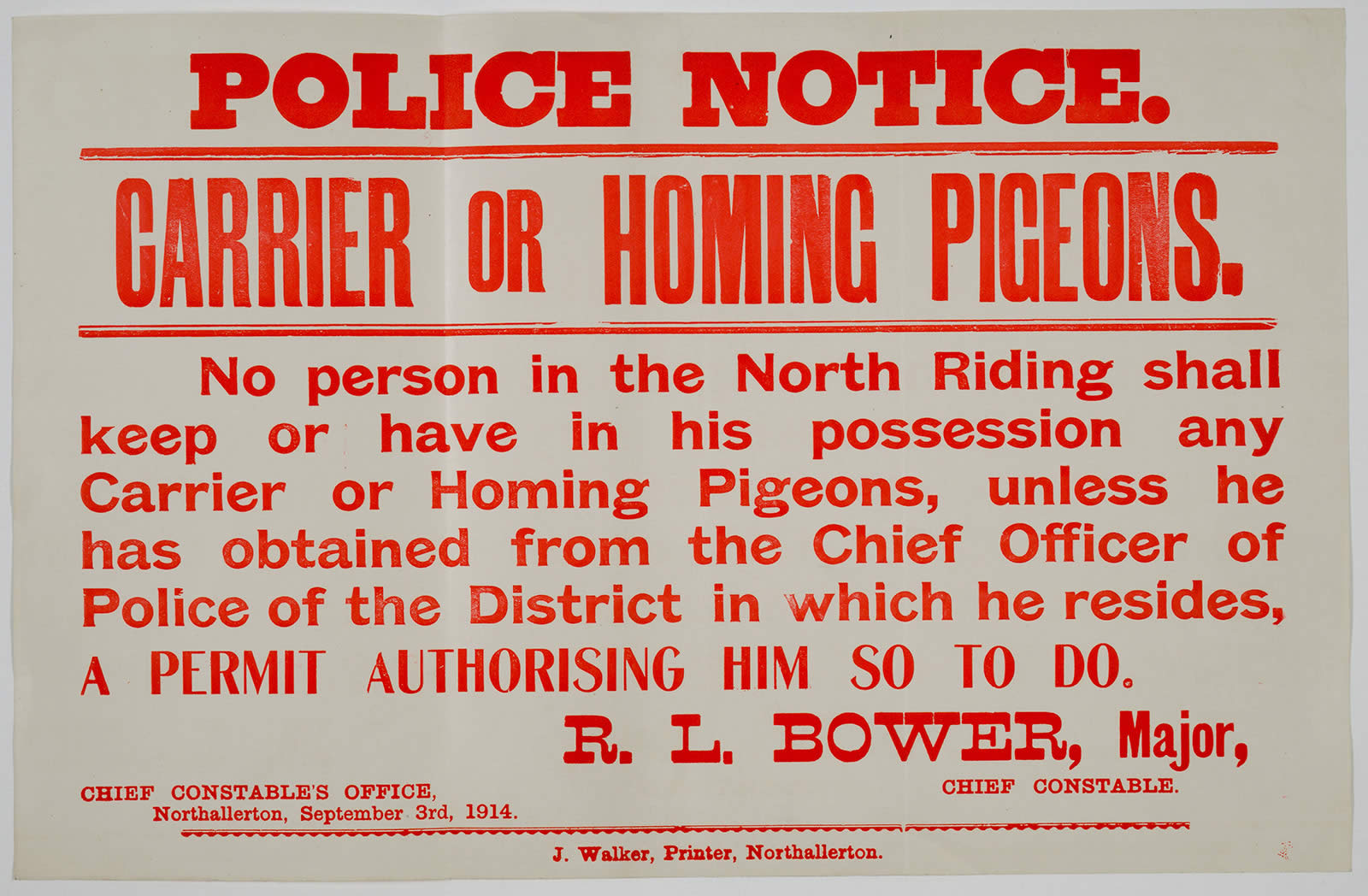

Under the Defence of the Realm Act 1914 nobody could keep homing or carrier pigeons without a permit from the police. The Home Office instructed Chief Constables across the East Coast to visit all owners of pigeons and release the birds – if they flew in the direction of mainland Europe, their owners would be under suspicion. A note from 10 Downing Street, apparently written by the Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith, suggested employing boy scouts to watch where pigeons were coming from. The Home Office wanted pigeons found ‘flying seaward in the early morning’ to be shot.

As the war raged on, officials started wondering how to stop people shooting pigeons. This change was largely thanks to the efforts of Mr A H Osman, later made Lieutenant Colonel Osman, the editor of ‘The Racing Pigeon’. He helped make officials aware of the valuable role pigeons could play in wartime communications, and became head of the Home Office Pigeon Service. The birds were vital to the army and navy – for example, they were used to communicate between Royal Navy ships that didn’t have wireless telegraph systems – so shooting them ran the risk of preventing important messages from being passed on. An amendment was made in January 1916 to the Defence of the Realm Act to ensure that shooting pigeons became an offence.

Police notice of 1914 warning owners of homing pigeons that they need a permit (catalogue reference: HO 45/10727/254753)