Love and war

The war caused new challenges for men and women wanting to get married: the legal technicalities could prove difficult for women with fiancés at the Front, particularly if they needed to marry urgently.

One pressing reason for a wedding was pregnancy. As well as the social stigma of unmarried motherhood, a family’s financial security was linked to marital status: wives received a higher rate of Soldiers’ Separation Allowance than the dependents of unmarried men. A widow would get a pension if her husband was killed in service.

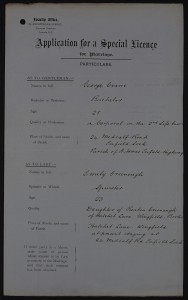

In January 1915 Corporal George Crane raced back from the Front to marry his pregnant fiancé Emily Greenough. Although George arrived home before the birth, the couple did not have time to marry before their child was born. On 13 January George applied for a special licence for a marriage to take place outside a church or register office. His leave was due to expire on 14 January and Emily was too ill to be taken by ambulance to a church to be married.

Local vicar the Reverend Pryce Jones was willing to perform the ceremony and supported George’s application, explaining that the pair had been due to be married before the war broke out, but that George had been ordered to the Front in a hurry. Happily the War Office granted George an extra 24 hours leave for the sole purpose of getting married, and the application was approved. George and Emily got married on 14 January, with the vicar reporting to the Registrar General that:

‘it would have given you sincere gratification to witness the sincere joy in that humble sick-room this evening. The Corporal goes back to the trenches a much happier man.’

- George and Emily’s application (catalogue reference: T 1/11828/22315)

- George and Emily’s application (catalogue reference: T 1/11828/22315)

Special licences of this nature were extremely expensive, costing £29 5s 6d at a time when a private might only receive between 1 or 2s a day in wages. In George and Emily’s case the vicar and superintendent registrar waived all but £5 of the fees, with an extra £5 stamp duty on top, which was later remitted by the Treasury.

But cost was not the only barrier to getting married in a hurry. Three weeks’ notice had to be given ahead of the intended wedding, for banns to be read or notice to be given at a Register Office. During this time both parties had to be resident in their named parishes.

In July 1915 the Reverend G Sanderson of Ripley, Derbyshire, wrote to the Registrar General on behalf of two soldiers from his parish who were serving in France and wanted to return home and get married. The men would only get four or five days leave at most, so they would have to apply for special licences and pay a £2 fee. The Registrar General responded by instructing his registrars to turn a blind eye to the rules:

‘no harm can come of this, because even though the notice does not literally comply with the requirements of the statutes… the validity of the marriage is not affected.’

On 20 September 1915 a General Register Office memorandum confirmed that a soldier or sailor’s permanent home address might be considered their home. From then on a woman could register notice of a marriage without their fiancé being present, and the short leave men received from the Front would not make marriage so difficult or expensive.