Fighting through food

As war broke out in Britain, its civilians had to become accustomed to food shortages. There was talk – both in government and on the streets of Britain’s cities, towns and villages – of the introduction of compulsory rations, and by 1917 the Cabinet were concerned that the country was going to run out of staples such as flour.

At first the government were unwilling to force rationing on the country, not only because it was likely to cause resentment, but also because German propaganda might seize upon the decision as proof of their submarines’ success in stopping vital food imports reaching British ports.

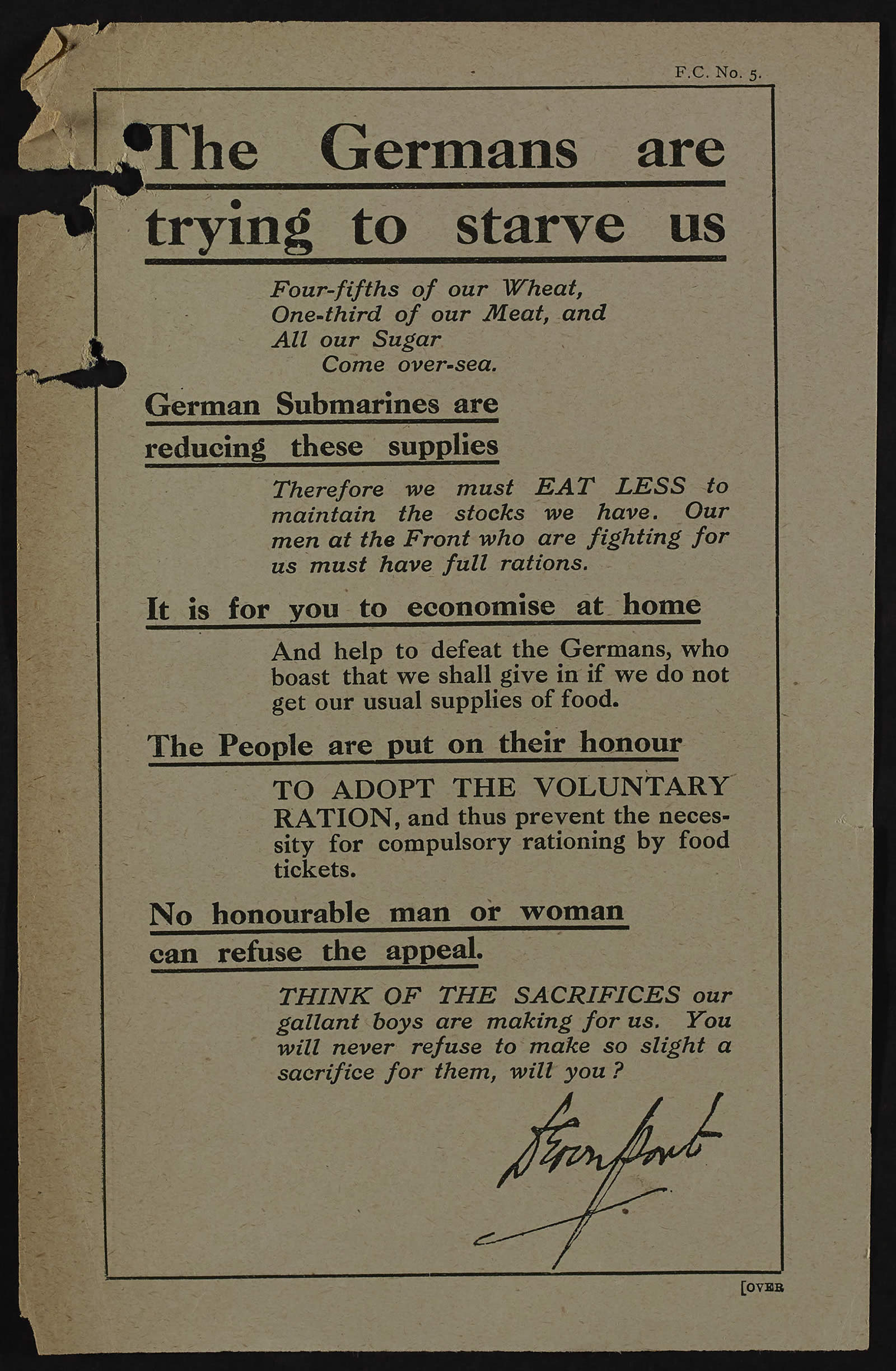

The government subsequently launched a propaganda campaign in 1917 to try and persuade people to adopt voluntary rations on their own terms. They did this by distributing Ministry of Food leaflets with statements such as: ‘Think of the sacrifices our gallant boys are making for us. You will never refuse to make so slight a sacrifice for them, will you?’

The language of the leaflets was designed to deliberately tap into civilians’ fears. One warns that ‘The Germans are trying to starve us’, suggesting that conserving food stocks is essential to avoiding defeat. ‘Our men on the Front who are fighting for us must have full rations,’ reads another line. On the back of the leaflet sits a cartoon of John Bull – a personification of England – standing on weighing scales. Bull is delighted that after beginning his rational service of voluntary rations he’s lost weight: ‘Sacrifice indeed,’ he says, ‘Why I’m feeling fitter every minute! And I’ve still got plenty of weight to spare’.

It was not long before voluntary weight-loss changed from a choice to a compulsory action. By early 1918, food was so scarce that the government introduced new laws that ensured rationing across everyday foods such as meat, butter and milk.

Leaflet produced by the Ministry of Food and National War Savings Committee in order to persuade British civilians to adopt voluntary food rations due to wartime shortages, 1916-1917 (catalogue reference: NSC 7/37)