Employing injured soldiers

Nearly six million British and German men were disabled by injury or disease between 1914 and 1918. Many returned home with paralysis due to damaged nerves; others came back missing one or more limbs.

The process in place to support the disabled men was lengthy. For some, it could take years to get through the hospital system. The men had to be seen by a specialist before being fitted with a prosthetic limb and the demand for prosthetics was enormous – as many as 41,000 limbless men returned to Britain from war.

Training schemes and workshops designed to help men use their new limbs and find employment were set up throughout the country at hospitals such as The Princess Louise Scottish Hospital for Limbless Sailors and Soldiers at Erskine in Scotland, and the Queen Mary Convalescent Auxiliary Hospital in London. The workshops were located in hospitals so that those waiting for treatment could be employed in useful and remunerative work. The numerous trades taught include cabinet making, carving, boot making, tailoring, basket making, bookkeeping, bricklaying and hairdressing.

Thomas Kelly, a private in the Gordon Highlanders, received a 100% disability pension after having both of his legs amputated above the knee. Kelly received 12 months of training in boot-repairing under the instruction of a private employer. However he wasn’t able to obtain employment as a boot repairer and was advised that he was unfit for such work.

Despite the difficulties he experienced, Kelly turned his attention to opening his own business – a tobacconist and newsagent’s shop – in 1921, which he funded with his own money. When the business began to struggle, Kelly received a grant for £40 from the Harry Lauder Million Pound Fund for Maimed Men, Scottish Soldiers and Sailors. This was a private fund that had been set up by the renowned Scottish singer and comedian Harry Lauder, who had a great deal of sympathy for those who had been significantly injured in the war.

Kelly eventually had to give up his business. A letter he sent to the Ministry of Labour shows that he was keen to continue in employment. After asking for training in basket making at Erskine House Kelly offered the following reminder:

‘I left a good job to join the soldiers, but now when I am maimed and not fit for manual labour, this country has no further use for us. Yet it was to be a country fit for heroes to live in. I think you will better let me know if you are going to give me training – yes or no. Then I will know how to act by writing to His Majesty and explaining my case to him.’

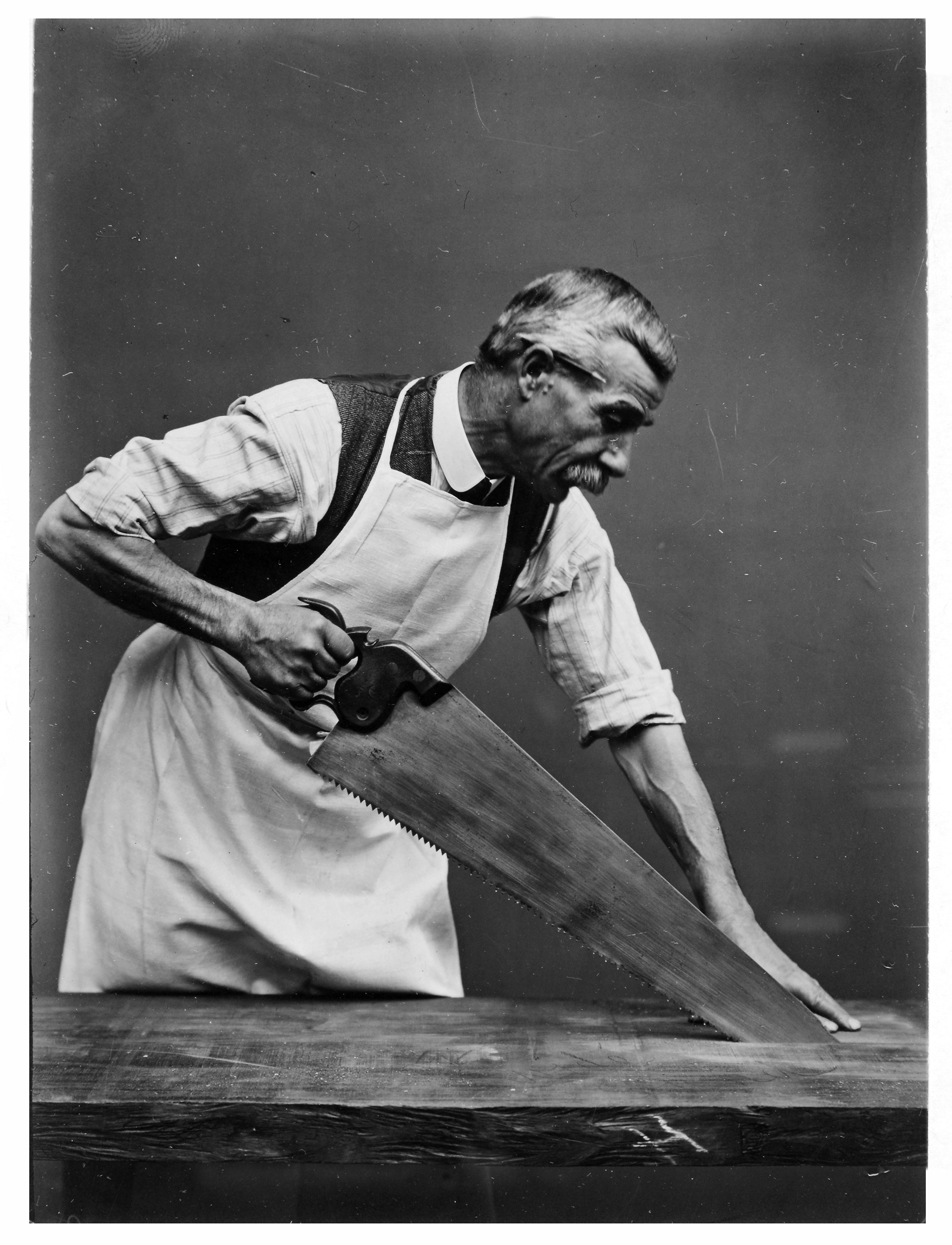

A participant in an experiment by the Artificial Limbs Section, 1918-1919. The aim of the research was to find out how arms and hands move while using hand-tools so as to develop better aids for injured soldiers (catalogue reference: MUN 7/331)