Colonial workers

The First World War saw many workers travel to Britain from the colonies in order to support understaffed industries.

Mr Robert Samuel Betty travelled to Britain from Jamaica in March 1916 ‘entirely from patriotic motives and had spent most of his money in doing so’. He was a highly-qualified chemist who had studied at the Pratt Institute in New York and worked in Chile.

On his arrival Betty signed up to the Professional War Service Register, looking for work in chemicals. He was offered a post at a factory, in Rainham, Essex, which produced a component of TNT, but by mid-April had been fired after being attributed as the cause of a dangerous incident.

Now struggling financially, he visited the Labour Exchanges and Unemployment Insurance Department at the end of April to protest that he had been unable to work in his expert field. A message sent to the Colonial Office about Betty’s visit states that he had been informed that ‘there was in fact practically no opening for white men as chemists’ and that ‘the colour question was mentioned quite frankly and amicably’.

During the previous month Betty had supposedly been offered – but turned down – roles unrelated to his field of training. After being offered a final option of repatriation to Jamaica, Betty was said to have responded in disgust and ‘went away with the apparent intention of committing suicide’.

The Labour Exchange official provided little sympathy, commenting that Betty ‘has postponed the attempt for a few days’ and that he did not feel that a man of ‘this peculiar temperament would carry out such an intention on impulse’. Further comments in the file suggest that the Whitehall officials’ preconceptions of Betty’s race and mental health also contributed to his treatment by the Colonial Office. Betty was described in his file as ‘a negro chemist’ with ‘a highly-strung and eccentric nature’. A clerk went as far as to suggest that ‘it is not very uncommon for destitute West Indians to threaten to commit suicide when disappointed in their application to the Colonial Office’ and that ‘they are so fond of dramatic and extravagant language that it is not unlikely that this threat may be mere words’.

The case of Robert Betty indicated the tension between the structures of colonial government and the optimism, skills and enthusiasm of the empire’s subjects. Negative conceptions of race and mental health within government institutions could also contribute to a rapid dismissal of those skilled subjects, as they slipped into a stark choice between hardship and repatriation.

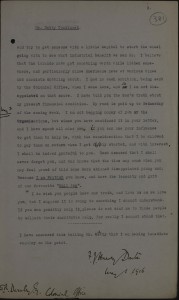

The day after his visit Betty accepted the offer of repatriation to Jamaica, with the stated intention of boosting the industries there. His letter included an impassioned plea:

‘And now sir, as you know well enough, my white brothers won’t have me here. I am sorry but I do not hate. I love this country and, after reconsidering, I do not want to be one of the sons to commit an act to besmirch her name. Forgive the things I said in the anguish of my soul…

Rest assured I will never forget you, and who knows that the time may come when you may feel proud of this same dark skinned disappointed young man. Because I am British you know, and have the tenacity and grit of our favourite “Bull Dog”…

I do wish you people knew our truth, and love us as we love you, but I suppose it is owing to something I cannot understand.’

Arrangements were made for Betty’s repatriation to Jamaica in the first week of June, just over a month after he made his appeal.

- Note from an official at the Professional Classes War Register to E R Darnley of the Colonial Office on the case of Robert Betty (catalogue reference: CO 137/718)

- Note from an official at the Professional Classes War Register to E R Darnley of the Colonial Office on the case of Robert Betty (CO 137/718)

- Note from an official at the Professional Classes War Register to E R Darnley of the Colonial Office on the case of Robert Betty (CO 137/718)